Editor’s Note: Technology offers many solutions for distributed learners. In 1998, PREL used satellite television to distribute lessons to the widely distributed islands in the Pacific region. In 2001, the Ohana Foundation offered a combination of DVD and internet technologies for this purpose. Today, with mobile phones as a ubiquitous source of interactive multimedia, it is adopted by the University of South Pacific for distance and flexible learning. TAFE in Australia are also experimenting with mobile phone technologies.

Negotiating Geographical Isolation:

Integrating Mobile Technology into Distance Education

Programmes at the University of South Pacific

Deepak Prasad

Fiji Islands

Abstract

The catchment area for the University of the South Pacific (USP) is enormous, stretching across 33 million square kilometres of ocean; communications of all kinds remain knotty even in the 21st century. Of the approximate 22,000 students currently enrolled at USP, more than half choose to study by distance and flexible learning (DFL). For these students, USP’s distance education network based satellite communications, USPNet, serves as a gateway for internet, phone and data links, audio and video conferencing, and video broadcasting, providing links with the University’s campuses. Even with this capacity, negotiating geographical isolation is not easy: not every DFL student can travel to the campus to use the USPNet facilities since many of them are studying in remote locations, and sometimes there is no electricity.

This paper focuses on finding cost-effective ways of linking with these students. Connecting via a mobile device appears to be an obvious answer. Following a review of mobile devices used by Mohamad and Woollard (2008), Kukulska-Hulme (2007), and Caudill (2007), this paper proposes the most accessible, cheap, and easy to use portable mobile device that can pave the USP region’s vast geographic spaces with new bridges of distance learning. The paper then considers strategies for using the indentified mobile device and presents a DFL communication model. The paper concludes that USP should not wait for the technology to improve in the USP region but rather use the currently available technologies to communicate with the remote DFL students.

Keywords: University of the South Pacific, USPNet, ICT, SMS, Vmail, Moodle, distance education, internet, mobile technology, m-learning, satellite, telecommunication.

University of the South Pacific, distance education, and distance students

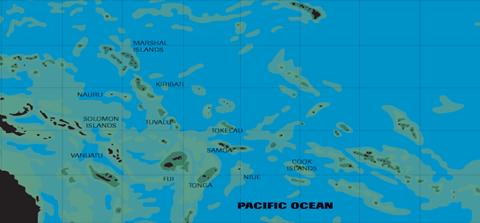

USP is a regional university serving 12 island countries: Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu and Samoa and offers almost 400 educational programmes via Distance and Flexible Learning (DFL) in a variety of modes and technologies throughout USP's 15 campuses. At the time of writing, 52% of USP’s 22,000 students are DFL scattered across 12 member countries. The USP member island nations are geographically dispersed extending from the Solomon Islands in the West to the Cook Islands in the East, spanning 33 million square kilometres with five time zones (Figure 1). Delivery of DFL courses across the vast area of the Pacific Ocean poses its own problems, challenges and barriers that are unique to its nature.

The University delivers DFL courses with a mix of printed materials, CDROMs and DVDs, audio and video tapes, online learning management system (Moodle), and audio and video conferencing offered through USPNet. The majority of DFL courses use live satellite-based audio tutorials and printed materials such as study guides, introduction and assignments booklets, readers and commercial readers as the most common form of delivery. In 2008, 396 of 402 DFL courses delivered live audio tutorials via USPNet.

Figure 1. University of the South Pacific region

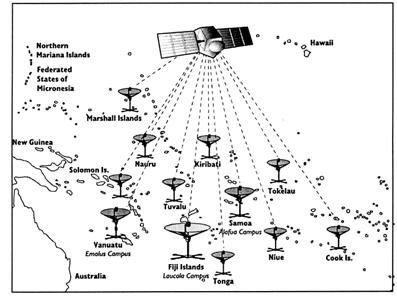

![]() USPNet is a USP owned Wide Area Network incorporating a 5MHz IP Satellite based technology (Figure 2). For USP's distant students and staff, USPNet provides for the opportunity to participate in interactive audio tutorials, (conducted from any campus), communicate by e-mail with a lecturer/tutor or another student, access the World Wide Web, access online MIS and banner applications, watch a live Video multicast, access multimedia material via Server downloads and live video conferences (and tutoring) with the Laucala Campus in Suva.

USPNet is a USP owned Wide Area Network incorporating a 5MHz IP Satellite based technology (Figure 2). For USP's distant students and staff, USPNet provides for the opportunity to participate in interactive audio tutorials, (conducted from any campus), communicate by e-mail with a lecturer/tutor or another student, access the World Wide Web, access online MIS and banner applications, watch a live Video multicast, access multimedia material via Server downloads and live video conferences (and tutoring) with the Laucala Campus in Suva.

Figure 2. USPNet serving USP campuses

USPNet is expected to help remove “the tyranny of distance” between the twelve geographically distributed USP member countries. Unfortunately, USPNet only connects to campuses, centres, and not to individual students in the region, “in effect limiting the power of the USPNet distance education model” (Chandra, 2002, p.86). Thus, only those students who can travel to campus or centres can use the study facilities provided by USP’s campus or centres. While other students’ study independently using print-based course materials. It is estimated that 20-30% of distance students do not have access to USPNet facilities (Wah & Tuisawau, 2000).

This paper aims to nominate a mobile device that could be utilised to communicate with distance students who can not travel to campus to use USPNet facilities, particularly due to distance or cost of transport. In doing so, the paper first provides readers with the review of literature on uses of mobile devices in education. Next, the paper identifies the most widely used ICT mobile device in the USP region. This will be followed by discussions on possible uses of the selected mobile device in the University’s context, conclusion, and possible directions for future research.

Literature Review

Mobile devices are pocket-sized computing devices that characteristically have a display screen with miniature keyboard or touch input. Mobile phones, pocket computers and PDAs (Personal Digital Assistants) offer web access, text messaging and voice options for Mobile Learning.

M-learning is defined as learning that takes place with the help of mobile devices. Mobile devices offer suitable educational environment to support learning activities both inside and outside the classroom (Fleischman, 2001). ICT (Information and Communications Technology) is the term, which functions as an umbrella for this paper, and beneath ICT lays the term m-learning.

Until now, no studies have been carried out to realize the potential of using mobile devices at the University of the South Pacific. Nonetheless, there are several studies that address the use of mobile devices in learning that can illuminate the potential of using mobile devices for the USP context. One study by Mohamad and Woollard (2008) investigated issues surrounding the realization of mobile learning in Malaysia. This study asserts that a user’s positive attitude is one of the factors that determine the success of employing mobile devices in education. Mohamad and Woollard suggest that teachers negative attitudes towards ICT can be replaced with a positive attitude if barriers in adopting ICT among teachers can be eliminated. They further state no significant difference in positive attitude towards ICT among students who own ICT and those who do not. Mohamad and Woollard (2008), conclude that similar to developed countries, mobile technology can be successfully implemented in the education system in the developing countries. However, the technology needs to be reformulated so that it is both suitable and sustainable in the situation of developing countries.

A study, by Kukulska-Hulme (2007), found that testing usability of mobile devices in education should not be just done once or twice during the life of the project but tracked from the inception use to the state of relative experience. Kukulska-Hulme observed that usability issues were often reported where PDAs were used and suggested that PDAs may have more usability problems than mobile phones. The Kukulska-Hulme study agreed with the Mohamad and Woollard (2008) conclusion about how the choice of the technology should be scenario-based. Where the Hulme study differed is that he pointed out that the owners’ familiarity with mobile devices avoids many potential usability problems for mobile learning.

Caudill conducted a study (2007) that explored the major mobile devices currently in use: PDAs, mobile phone, and MP3 players. Caudill’s findings aligned with Kukulska-Hulme’s study in that both say that ownership and access to mobile devices is paramount for the success of m-learning system. Caudill’s study found that it is critical for m-learning designers to be aware of the kind of device their intended audiences are working on, and apply specific pedagogical theories connected to the devices

The main concept that all three educational researchers supported was that mobile technology has the potential to support learners anywhere and at anytime. All studies revealed that every technology does not work for every student and situation. In addition, the educational researchers found that the success of m-learning depends on the student’s ownership and familiarity with the mobile technology. As Okamura and Higa (2000) note, the use of various technologies is required for effective distance learning in the Pacific.

Selecting Mobile Devices

A large proportion of the Pacific region population is ICT-savvy (Williams, 2007). They have a positive attitude towards ICT knowing that ICT can link them to the global world. This is very encouraging. Mohamad and Woollard (2008) assert that people should have positive attitudes towards ICT for its successful implementation in the m-learning system. Success of m-learning also depends on factors like ownership and access to mobile devices (Caudill, 2007; Kukulska-Hulme, 2007). Hence, it is very important to choose technology that is available to majority population of the USP region. Williams (2007), claim that a large part of the Pacific region have access to internet and 3GSM phones. This indicates that out of all possible mobile devices, mobile phones are most dispersed in the Pacific. Thus, USP should adopt mobile phones for its m-learning system.

It is also vital to note the penetration of the internet in the USP region as it has implications for the type of activities that can be facilitated via mobile phones. Penetration of mobile phones in Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and other Pacific countries is higher than the penetration of the internet as the following statistics show:

| Mobile Phone | Internet | |

| 63.20 | 9.36 |

|

| 0.75 | not available |

|

| 2.20 | 1.63 |

|

| 46.37 | 8.37 |

|

| 11.50 | 7.52 |

|

| 45.98 | 4.46 |

|

Data source: International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

If one looks at the comparative figures of users on internet and mobile phone, it can be safely assumed that an activity that may be facilitated via mobile phones has to be internet independent. At this point, it is important to understand that “mobile learning has lot of potential for quick and wide reaching out to the geographically wide-spread learners, even though they have no internet connectivity” (Dharankar, 2008, p.2)

Fitness for purpose

Mobile phones “are not designed with the education market in mind” (Peters, 2007). However, many educational researchers and educational providers recognize the benefits of mobile phones in education (Mohamad & Woollard, 2008; Kukulska-Hulme, 2007; Caudill, 2007). The mobile phone fits perfectly with USP context as it is most accessible mobile device that does not depend on the electricity since it can be charged using solar chargers or cigarette lighter socket in cars. Mobile phones have host of tools that can support distance education. Tools that are available on phones differ according to their model and manufacturer. For USP’s purpose, only basic tools available on 3GSM phones will be considered that are internet independent. These features are as follows:

- Calling and receiving calls;

- Voice messaging: allows the phone to act as an answering machine;

- SMS (Short Message System): support for text messaging – limited to 160 characters;

- Audio recording: may record an audio while user is communicating with another party on the mobile phone - dependent on the phone’s memory capacity; and

- Conference call: support for small conference – up to five people at once.

Common problems of DFL students

American philosopher John Dewey once said, "A problem well stated is a problem half solved". Thus, it is only proper to state the problems of distance learners at USP before making recommendations. The most salient problems of distance learners at USP due to geographical isolation can be summarized as follows:

- Tutors do not show up for the audio tutorial. Students may have come a long way to attend. (Suzuki, 2004);

- Isolation: no one to talk to (Mugler & Landbeck, 1998; Chand, 2007; Suzuki, 2004; Deo & Nabobo, 2003; Agassi, 2003 );

- Delay in receiving feedback on assignments (Wah & Tuisawau, 2000; Suzuki, 2004);

- Limited access to available support – students can not travel to campus to attend audio tutorials (Chand, 2007; Bolobola & Wah, 1995); and

- Lack of administrative support – lack of sufficient academic advisors (Bolobola & Wah, 1995; Suzuki, 2004)

How mobile phones can help: Closing the distance

Problems identified above can be solved with the use of mobile phones by carrying out the following activities:

- SMS message can be used to inform the students about the cancellation of audio tutorials.

- Students could communicate with their peers by either using SMS or by calling each other. In addition, students can make conference calls on the mobile phones and have group discussions.

- Assignment marks and feedback can be given out either by calling individual students or by using SMS.

- Students can either call or SMS directly to tutors for advice. Students can also call their local campus and participate in the live audio tutorials. Audio tutorials can be recorded by the campuses and these can be made available to students. Students can access these tutorials by calling their local campuses, whereby campus staff can play the pre-recorded tutorials. Students can listen and record these tutorials by using the audio recording tool on the mobile phones.

- SMS message can be sent reminding students about fees arrears, exam date and venue.

Mobile phones provide a viable avenue for initiating contact or sending out reminders. SMS is very reliable method of communication and it is less expensive to send an SMS than to mail a reminder through regular postal mail. A mobile phone is portable hence; people always carry it with them. Therefore, individuals are likely to receive and respond to SMS messages more quickly and probably more reliably than they are to email.

Putting into practice: Distance and Flexible Learning communication model

Myriad of factors and processes will be involved, depending on the type of interaction and the type of mobile phone tool used to establish communication.

The following figure 3 demonstrates a proposed DFL communication model.

Figure 3. Proposed DFL Communication Model

Figure 3. Proposed DFL Communication ModelThe model above depicts that students can establish: (i) student-student interaction, (ii) student-campus interaction, (iii) student- lecturer/tutor interaction and (iv) student-peer group interaction. Different factors and processes will be involved in all the 4 types of interaction. The purpose of the communication will determine the process and function of the mobile phone used. For interactions (i), (ii), and (iii) students can either call or use Small Message System (SMS) functions. As for interaction (iv) conference call function can be used. Students have only the mobile phone to send and receive communication. However, use of mobile phones is not practical to use SMS from the lecturer/tutor and campus end. Mobile phone is not practical in terms of high cost that will arise by communicating with many students. For example, if a lecturer sends SMS to 250 students at a cost of .20 cents per SMS, the total cost will be $50.00.

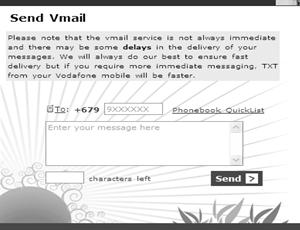

Figure 4. Vmail interface

Figure 3 show that lecturer/tutor and campus will be making 1-many communications: lecturer/tutor-peer group and campus-peer group. Therefore, it is proposed to make use of free SMS services provided by the mobile companies operating in the USP region. For instance, Vodafone is one of the 2 mobile phone companies in Fiji and provides free SMS service known as Vmail (Figure 4).

One obvious problem with Vmail service is that messages may be delivered late. For USP’s situation, Vmail service could be even more useful if it had the ability to send bulk messages. Bulk messages means sending 1 message to many recipients. With the Vmail’s current capacity, lecturers/tutors together with the campus staff will spend a lot of time if they would want to send messages to many students. This may discourage the lecturers/tutors from using the Vmail system. To solve this problem USP will need to collaborate with Vodafone and reach some form memorandum of understanding so that Vodafone gives special access to USP staff to send bulk messages. Therefore, for successful implementation of the proposed model, USP needs to work with the mobile telecommunication companies of each of the USP member countries.

Conclusion

The complexities and constraints involved in enabling effective m-learning are being researched with in both developed and developing countries. The general development of ICT in the Pacific provides a context in which “the diverse characteristics of the islands themselves compound the challenges” (Williams, 2005, p.2). While some USP member countries have support from their governments others face the limitations of telecommunication monopolies, lack of infrastructure and resources that cause hindrance in the “the rapid development and use of ICT” (Williams, 2005, p.2). Assuming that ICT is a bridge too far for the Pacific and that other kinds of development must come first will further delay in negotiating geographical isolations for USP distance students. The Deputy Vice Chancellor of USP has rightly pointed out:

The

In an effort to catch up with the developed countries and primarily to provide a means of communication for remote distance students of USP, it is suggested that USP should resort to mobile phones to communicate with the DFL students who are widely dispersed over vast oceanic spaces. Mobile phones have a few weaknesses such as: added cost to the students, limited storage space, and limited SMS length. However, USP should not wait for the technology to become more affordable and accessible, and expect USPNet provision to improve in the anticipation of taking education to more remote students. Rather, USP should explore further the possibility of using mobile devices that are broadly available to the Pacific Islanders today.

Future Direction

Beyond the already interesting potential of mobile phones to communicate with distance students in the remote location of the Pacific, several very interesting questions arise in this paper. It would be useful for researchers from USP, to conduct further research to acquire a better understanding of distance students’ perspective, strategy use, skills, and lecturers’ views about using mobile phones in distance education.

The University of the South Pacific serves a vast region in which making regular contact with distance learners remains a challenge for most students and lecturers. Reflective review of all stakeholders’ perspective is therefore essential, so that researchers and educators do not ignore those students who study by distance mode.

References

Agassi, A. (2002). A Distance Learning Application of the Solomon Islands People First Network (Pfnet): Project Proposal. Retrieved January 3, 2009 from http://www.idrc.ca/en/ev-61562-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html

Bolobola, C., & Wah, R. (1995). South Pacific women in distance education: studies from countries of The University of the South Pacific: Suva: University Extension, USP.

Brandjes, D. (2002). School networking in a Pacific Island states: An environmental scan and plan for the establishment of schoolnets for the Pacific Island states. The common wealth of learning. Retrieved December 9, 2008 from http://www.col.org/colweb/webdav/site/myjahiasite/shared/docs/02SchoolnetPacific.pdf.

Caudill, J. (2007). The Growth of m-Learning and the Growth of Mobile Computing: Parallel developments. International review of research in open and distance learning, 8(2). Retrieved December 12, 2008, from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/348/873

Chand, R. K. (2007). Same Size Doesn’t Fit All: Insights from research on listening skills at the University of the South Pacific (USP). International review of research in open and distance learning, 8(3). Retrieved December 12, 2008, from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/383/978

Chandra, R. (2002). School Networking in the Pacific Island States. Retrieved December 4, 2008 from http://209.85.173.132/search?q=cache:iYffoO7CyqAJ:www.col.org/colweb/webdav/site/myjahiasite/shared/docs/

02SchoolnetPacific.pdf+tanna+uspnet&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=8&gl=fj

Deo, B. & Nabobo, U. (2003). Reflections on mixed mode and multi-mode teaching: USP case study. Retrieved December 13, 2008 from http://www.odlaa.org/publications/2003Proceedings/pdfs/deo.pdf

Fleischman, J. (2001), Going Mobile: New Technologies in Education, Converge Magazine

Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2007). Mobile usability in educational context: What have we learnt? International review of research in open and distance learning, 8(2). Retrieved December 12, 2008, from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/356/879

Mohamad, M. & Woollard, J. (2008). Why does Malaysia need to consider mobile technology: Review of current practices to support teaching and learning with school-age children. Retrieved January 21, 2009 from http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/52455/01/MariamMohamad&JohnWollard.pdf

Mugler, F., & Landbeck, R. (1998). “It’s just you and the books”: Learning conditions and study strategies of distance learners at the University of the South Pacific. In J.F.J. Forest (Ed.) University teaching: International perspective (pp. 113 - 135). New York: Garland.

Okamura, N. H., & Higa, C. (2000). Distance education learning technologies and applications in the Pacific islands: A focus on interactive technologies. In R. Guy, T. Kosuge, and R. Hayakawa (Eds.), Distance learning in the South Pacific: Nets and voyages (pp. 183–212). Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, and Pacific Island Nations Fund, Sasakawa Peace Foundation.

Peters, K. (2007). m-Learning: Positioning educators for a mobile, connected future. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 8(2). Retrieved December 12, 2008 from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/350/914

Suzuki, K. (2004). Online instructional design: Workshop for distance and flexible learning. Retrieved December 18, 2008 from http://www.usp.ac.fj/jica/resources/documents/pdf_files/suzuki_presentation/workshopDay1.pdf

Wah, R. and Tuisawau, P. (2001). Flexible delivery at University of the South Pacific: No mean feat. Proceedings of the second Pan Commonwealth Forum on Open Learning, Commonwealth of Learning, South Africa.

Williams, E. B. (2005). Pacific Island States. Digital Review of Asia Pacific 2005-2006. Retrieved December 4, 2008 from http://digital-review.org/05_PacificIsland.htm

Williams, E. B. (2007). Pacific Island States. Digital Review of Asia Pacific 2007-2008. Retrieved December 4, 2008 from http://www.idrc.ca/fr/ev-127150-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html

About the Author

Deepak Prasad is Educational Technologist, Centre for Flexible and Distance Learning, University of South Pacific, Fiji Islands. He is a BTech in Electrical and Electronics Engineering, BA in Education, a Postgraduate Certificate in Educational Technology, and Diploma in Tertiary Teaching. His research interests are m-learning and its applications in open and distance learning.

Email: deepak.v.prasad@gmail.com