| August 2006 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: As distance learning spreads to all parts of the globe, it stimulates research to determine acceptance and ways to make it more effective. Online learning is becoming pervasive across barriers of language and culture, age and disability, geography and distance from population centers. Great centers of commerce such as Hong Kong now benefit from distance learning to enable “education for all.”

Perceptions of Students on

Online Distance Learning in Hong Kong

Harrison Hao Yang and Fung Chun Lau

Hong Kong

abstract

The Open University of Hong Kong (OUHK) is the first higher education institute introducing distance education in Hong Kong, and has been playing the central role on online distance learning in that region. This study reports the overview on the perceptions of students on online distance learning at OUHK. It intends to offer a glimpse into students who enrolled in two different online courses (n = 64) with the objective of investigating their views and opinions related to the Online Learning Environment (OLE) and the Interwise system, which are mainly used asynchronously and synchronously for teaching and learning, respectively. The Online Distance Learning Questionnaire Form is developed for this study, and a comparison between two courses on the OLE is conducted. Conclusion and discussion of online distance learning at OUHK are provided.

Keywords: perceptions; online learning; distance education; asynchronous and synchronous communication

Introduction

Online distance learning represents a new paradigm which deeply affects education in general. Many of the traditional face-to-face classroom activities can be reconstructed through web-based distance learning such as conferencing, electronic mail, and bulletin. Students and instructors can work at their own pace and at locations they are able to control (Edelson, 1998; Berge, 1999; Spiceland & Hawkins, 2002).

Asynchronous communication has been recognized more common than synchronous communication for online distance learning (Jonassen, 2000). There are two noteworthy advantages of asynchronous learning: first, it makes the convenience and flexibility offered by the “anytime, anywhere” accessibility (Richardson & Swan, 2003); second, “it allows students to reflect upon the materials and their responses before responding, unlike traditional classrooms” (Richardson & Swan, 2003).

Synchronous learning, on the other hand, has some of unique advantages, such as: “sense of immediacy is compelling. Live interactions produce more motivation to contribute” (Jonassen, 2000). One way or another, online distance learning has been widely used by institutions around the world. The Open University of Hong Kong (OUHK) is the only higher education provider to students with distance learning mode for every program in Hong Kong. OUHK believes that every aspiring adult should be given a chance to get higher education. With the philosophy of “education for all”, the university admits any Hong Kong resident aged 17 or above. The students are pursuing their studies by part-time genre in distance education. The Online Learning Environment is the first online system which has been developed for delivering online courses asynchronously by OUHK. In addition, a newly developed synchronous learning system Interwise has been employed for supporting online teaching and learning since April 2005.

While online distance learning programs are expanding, and participants are mounting globally, the question of how effectively to design and conduct online courses to students who are physically and/or timely separated from each other has been raised (Palloff and Pratt, 1999; Rovai, 2002; Yang & Maina, 2004). Such separation may increase social insecurities, communication anxieties, and feelings of disconnectedness (Kerka, 1996; Jonassen, 2000), as a result, “the student become autonomous and isolated, procrastinate, and eventually drops out” (Sherry, 1996). Previous studies suggest that successful online courses relate to interactivity, sense of well-being, quality of the learning experience, and effective learning (Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, and Archer, 2001; Rovai, 2002).

In order to identify the factors which attribute to the success of online courses, researchers believe that students’ perceptions of distance learning program is a prime area where should be focused on (Richardson & Swan, 2003; Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, and Archer, 2001). It is well documented about students’ perceptions of online distance learning in general (Romiszowski & de Haas, 1989; Romiszowski & Jost, 1989; Allen, Bourhis, Burrell, & Mabry, 2002; Picciano, 2002; Richardson & Swan, 2003; Yang & Maina, 2004).

There are sufficient studies examining on one online environment and/or comparing that to traditional face-to-face class, little is done on systematically and authentically investigating students’ perceptions on online distance leaning with more than one online environments and courses. This study intends to investigate views and opinions from students of two online courses at OUHK using the Online Learning Environment and the Interwise system, which are mainly used asynchronously and synchronously for teaching and learning, respectively.

Online Learning Environment and the Interwise System

The Online Learning Environment (OLE) is the first online system developed by the Open University of Hong Kong for delivery of the university’s online courses asynchronously. The OLE contains the online platform which consists of five major areas for the online course: news, schedules, interactive tools, course materials, and assignments (see Figure 1). In this online learning platform, users (students, tutors and the course coordinators) can post their questions, answers, and ideas or opinions on the discussion board of each module. Students can submit their learning assignments and materials electronically. Besides, users can get emails and send out any message to others privately or publicly (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Course Map of Online Learning Environment

Figure 2. Individual Platform of Online Learning Environment

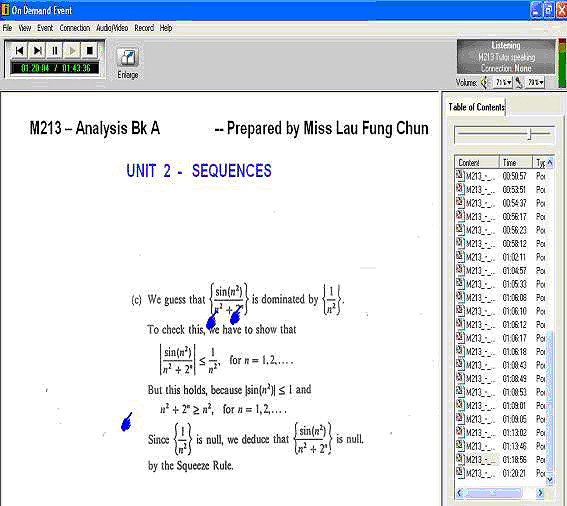

Other than the provision of the OLE, OUHK launched its newly developed Interwise system starting April 2005. The Interwise is a live and interactive distance learning system (see Figure 3). In the Interwise system, the students can join in the i-Classes which are scheduled by the tutors or course coordinators at any place. They can synchronously view whatever the tutors and coordinators are doing on the Whiteboard; converse and exchange notes with others; answer verbal questions and respond to the structured questions; record a live lesson, and play back live or pre-recorded lessons; etc. The Interwise environment enables the tutors and course coordinators to emphasize verbal instruction; to use a Whiteboard for displaying of learning materials; to operate the fully-monitored instruction during the “live” lessons; to ask questions and give tests, to conduct surveys and poll the students’ responses; and to share an application with the class or an individual participant, etc (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. Course Map of Interwise System

Figure 4. Screenshot of One i-Class in Interwise System

Method

Design and Instrument

To measure students’ perceptions of learning on online distance education at OUHK, and to preserve anonymity and voluntariness, an inclusive questionnaire was developed based upon two perspectives. On one hand, items were extracted and adapted from previous related studies, and the students’ survey on the usage of OLE at OUHK. On the other hand, the interview was conducted with a small sample of 8 students about perceptions of online education through their learning experiences at OUHK. During the interview, following questions were asked and discussed:

What do you know about the Online Learning Environment?

Do you enjoy using public forums such as the Discussion Board in the OLE?

Do you find the communication easier among you, classmates, the tutors, and the course coordinators by using the OLE?

Does the OLE give knowledge which makes you enjoy your learning more?

Do you gain any knowledge or raise any concern from using the OLE system?

Do you consider the course materials useful in your discussion?

Do you consider the tutorials helpful for your understanding of the topics?

What do you know about the recently introduced Interwise system?

Have you participated in an i-Class in the Interwise system?

Do you think that the Interwise system is an effective system to teach mathematics and/or statistics contents?

The final version of Online Distance Learning Questionnaire Form for the cross-sectional survey consisted of respondents’ personal data and perceptions of Online Learning Environment, the OLE course, and the Interwise system.

Participants and Procedure

The participants of this study were selected from students (n = 78) who enrolled two online courses MDST242 Statistics in Society (Course One) and M213 Linear Algebra and Analysis (Course Two) at OUHK in Spring 2005. Despite focusing on different subject areas, both courses had the similarities of course design and activities. Both courses shared the nature of using numerical data to understand patterns and relationships, and had been offered on the same difficulty level by OUHK. Most of participants in both courses were part-time students whose ages were in 20-30. In addition, one of researchers on this study was a tutor for both courses.

All 78 students received the Online Distance Learning Questionnaire Form, along with the information of explanation of this study and of how to complete the questionnaire survey form. Upon the deadline for completion of the questionnaire on March 12, 2006, 64 questionnaire forms were returned (Course One: n = 34; Course Two: n = 30), of which 64% were sent by male students and 36% were sent by female students, and all 64 forms were completed and usable. The return rate was 82%.

Results

Respondents’ Perceptions on Online Learning Environment (OLE)

Most of the students (70%) from both courses agreed that in general, they were satisfied with the OLE. About 63% of the students indicated that it was very easy to access the OLE, and nearly the same amount of them agreed that they found online communication with tutors helpful for their studies. About 53% of the students indicated that it was always beneficial to know the standard of the work expected. About half of the students concurred that the interface of the OLE was well designed (52%), and the program required them to describe and analyze data (47%).

Table 1

Comparison of the Frequency of Using OLE Features

Item | Course One | Course Two | t | ||

M | SD | M | SD | ||

Checking News posted by the course coordinator | 2.35 | .49 | 1.97 | .61 | 2.81* |

Reading online course materials | 1.94 | .69 | 2.13 | .35 | -1.43 |

Reading messages posted on the Discussion Board | 2.38 | .60 | 2.57 | .50 | -1.32 |

Posting messages on the Discussion Board | 1.74 | .67 | 1.88 | .65 | -.87 |

Communicating with your tutor or other students using emails | 1.68 | .53 | 1.80 | .66 | -.82 |

* p < .05.

In the comparison of the two courses, as indicated in Table 1, there were five items investigating on how frequently students used OLE features. Each item was on a scale of 1 to 3 with 3 being “often (4 times or more per week)”, 2 being “sometimes (1-3 times per week)”, and 1 being “none (0 times per week)”. One notable difference was found between students in Course One (Statistics) and Course Two (Linear Algebra) on the frequency of checking “News” posted by the course coordinator. The mean for the 34 students in Course One was 2.35 (SD = .49) while the mean for the 30 students in Course Two was 1.97 (SD = .61). This difference was significant (t = 2.81, df = 62, p < .007), which indicated that the students in Course One checked news which posted by the course coordinator much more times per week than the students in Course Two did.

Table 2

Comparison of Perceptions on the OLE

Item | Course One | Course Two | t | ||

M | SD | M | SD | ||

It is easy to access the OLE | 1.97 | .80 | 1.63 | .49 | 2.01* |

The interface of the OLE is well designed | 2.38 | .85 | 1.93 | .74 | 2.24* |

The immediate feedback for the online activities/exercises is useful and convenient | 2.44 | 1.02 | 2.23 | .73 | .93 |

The information obtained via links is helpful to my study | 2.35 | .92 | 2.23 | .73 | .57 |

The OLE makes communication with other students more convenient | 2.18 | .87 | 2.03 | .72 | .71 |

Online communication with tutor is helpful for my study | 2.13 | .91 | 2.37 | .93 | -1.04 |

It is convenient to submit my assignment via OLE | 2.38 | 1.48 | 2.77 | 1.17 | -1.15 |

In general, I am satisfied with the OLE | 2.03 | .87 | 2.23 | .73 | -1.01 |

* p < .05.

As indicated in Table 2, there were eight items investigating on how students perceived the Online Learning Environment. Each item was on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being “strongly agree” and 5 being “strongly disagree”. Significant differences were found between students in Course One and Course Two on two items: “It is easy to access the OLE”, and “The interface of the OLE is well designed”. The mean for the students in Course One regarding the accessible of OLE was 1.97 (SD = .80) while the mean for the students in Course Two on the same item was 1.63 (SD = .49). This difference was significant (t = 2.01, df = 62, p < .049), which indicated that the students in Course Two agreed more on “it is easy to access the OLE” than students in Course One did. The mean for the students in Course One regarding the design of OLE was 2.38 (SD = .85) while the mean for the students in Course Two on the same item was 1.93 (SD = .74). This difference was significant (t = 2.24, df = 62, p < .029), which indicated that the students in Course Two agreed more on “the interface of the OLE is well designed” than the students in Course One did.

Respondents’ Perceptions on the OLE Course

Although most students (85%) from both courses preferred face-to-face tutorials other than online discussion board (Open Forum) in Online Learning Environment, the majority of them agreed that in general, they were satisfied with the OLE courses. About 80% of students indicated that they liked the OLE discussion board. Approximately 62% of students pointed out that the email feature for online communication with the tutor was very helpful.

In the comparison of the two courses, as indicated in Table 3, there were ten questions on the online course design and development. Students were asked to indicate what extent they thought on each question. Each question was on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being “not at all” and 5 being “very much”. No significant differences were found between the students in Course One and Course Two on those questions.

Table 3

Comparison of Perceptions on the OLE Course Design

Item | Course One | Course Two | t | ||

M | SD | M | SD | ||

Was the level of difficulty of the materials appropriate to the subjects matter content? | 2.97 | .76 | 3.20 | .81 | -1.17 |

Was the presentation of the contents relevant to the course objective? | 3.85 | .74 | 3.87 | .68 | -.08 |

How presentable and attractive do you find the course materials? | 3.38 | .60 | 3.60 | .67 | -1.36 |

Were the course materials designed to be user-friendly? | 3.56 | .75 | 3.57 | .73 | -.04 |

How satisfied were you with the quality of tuition / support you received from the tutors? | 3.65 | .73 | 3.60 | .67 | .27 |

How well were you able to learn from your tutor’s comments? | 3.76 | .70 | 3.70 | .60 | .40 |

How much did the program require you to memorize facts / concepts? | 3.44 | .61 | 3.40 | .62 | .27 |

How much did the program require you to understand facts / ideas? | 3.79 | .69 | 3.70 | .70 | .54 |

How much did the program require you to apply learning to your own experience / life / job? | 2.85 | .70 | 3.00 | .74 | -.81 |

How much did the program require you to analyze data / descriptions / arguments? | 3.44 | .82 | 3.27 | .91 | .81 |

As indicated in Table 4, there were nine items investigating on how students perceived their learning through the online course. Each item was on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being “strongly disagree” and 5 being “strongly agree”. The item “Tutorials have helped my understanding of the topics covered in this course” had the highest means from both courses, followed by items “Tutorials were well integrated with the rest of the course”, “The course sharpened my analytic skills”, and “The course developed my problem-solving skills”. Significant differences were found between students in Course One and Course Two on two items: “It was always beneficial to know the standard of work expected”, and “The tutor of this course motivated me to do my best work”. The mean for the students in Course One regarding the standard of work expected was 3.68 (SD = .68) while the mean for the students in Course Two on the same item was 3.03 (SD = .93). This difference was significant (t = 3.18, df = 62, p < .002), which indicated that the students in Course One agreed more on “it was always beneficial to know the standard of work expected” than the students in Course Two did. The mean for the students in Course One regarding the motivation from the tutor on doing their work was 3.71 (SD = .63) while the mean for the students in Course Two on the same item was 3.37 (SD = .49). This difference was significant (t = 2.38, df = 62, p < .020), which indicated that the students in Course One agreed more on “the tutor of this course motivated me to do my best work” than the students in Course Two did.

Table 4

Comparison of Perceptions on the OLE Course Learning

Item | Course One | Course Two | t | ||

M | SD | M | SD | ||

It was always beneficial to know the standard of work expected | 3.68 | .68 | 3.03 | .93 | 3.18* |

The course developed my problem-solving skills | 3.56 | .70 | 3.60 | .50 | -.27 |

The tutor of this course motivated me to do my best work | 3.71 | .63 | 3.37 | .49 | 2.38* |

The workload was too heavy | 3.18 | .83 | 3.43 | .82 | -1.24 |

The course sharpened my analytic skills | 3.68 | .73 | 3.80 | .41 | .85 |

The course improved my skills in written communication | 3.18 | .80 | 3.37 | .81 | -.95 |

Tutorials have helped my understanding of the topics covered in this course | 4.09 | .57 | 4.13 | .35 | -.38 |

Tutorials were well integrated with the rest of the course | 3.76 | .61 | 3.70 | .47 | .47 |

The tutor encouraged my interest in the course topics | 3.68 | .73 | 3.40 | .62 | 1.62 |

*

p < .05.Respondents’ Perceptions on the Interwise System

Approximately 86% of the students took part in the newly introduced Interwise section. Among of them, about 80% of the students agreed that the Interwise system was helpful to their studies, and about 78% of the students agreed that they could understand mostly what the tutor delivered in this Interwise system. About 85% of the students who attended the Interwise section indicated that they would continue to participate in it. The main reasons for 14% of the students who could not attend the Interwise section were the time conflict, computer hardware and/or software problem. All of the students who could not attend the Interwise section indicated that they would try to participate in it in the near future. Overall, about 82% of the students felt that the tutor could deliver the topic clearly to them by using the Interwise system.

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of this study indicated that students perceived very positively on learning in asynchronous online environment. This result is consistent with the findings of previous research (Romiszowski & de Haas, 1989; Romiszowski & Jost, 1989; Allen, Bourhis, Burrell, & Mabry, 2002; Picciano, 2002; Richardson & Swan, 2003; Yang & Maina, 2004). Most of the students were satisfied with the usage of OLE. They felt that features in asynchronous online environment such as discussion board, email and tutorials were helpful and useful to their studies. Students from both courses strongly sensed that the OLE course had helped their understanding of the topics, sharpened their analytic skills, and developed their problem-solving skills.

Results revealed that there were significant differences between students’ perceptions in two courses on: 1) the frequency of checking news posted by the course coordinator; 2) the accessibility of the OLE; 3) the design on the interface of the OLE; 4) the benefit of knowing the standard of work expected; and 5) the motivation from the tutor. It appeared that students who perceived more importance on knowing the standard of work expected were likely to check the news posted by course coordinator much more times per week than students who perceived less importance on knowing the standard of work expected were. Correspondingly, regarding to do their best work, students who perceived more importance on knowing the standard of work expected emphasized more importance on the motivation from tutor than students who perceived less importance on knowing the standard of work expected did. It was interesting to note that students who felt the greater easiness to access the OLE would also express the greater approval to the design on the interface of the OLE. Perhaps students’ perceptions on the accessibility of online environment were a factor which influenced students’ comfort, satisfaction, and preference on the design of course interface.

The fact that most students showed optimistically on the Interwise system for helping their studies should be of interest to program leaders, system designers, course coordinators, and tutors. Online distance learning through newly developed synchronous environment can transmit “live” data including audio, video, texts, files, screens, pictures, and shared applications (Jonassen, 2000). This type of online distance learning can be particularly helpful for delivering courses which involve demonstrations and discussions on patterns and relationships, hands-on activities, etc. Although results reveal that time conflict and technical difficulty are still remaining, the continuation of using synchronous system to support online distance learning with more flexible scheduling and appropriate training seems to be quite encouraging and promising.

One weakness in this study was the sampling. It should be noted that the sample size was relatively small. Furthermore, the participants were selected by the convenient sampling method since one of researchers for this study was a tutor of both courses for the time being. Hence, the results of this study might not represent larger populations’ perceptions on learning in online distance education. This weakness should be controlled in future studies.

References

Allen, M.; Bourhis, J.; Burrell, N.; & Mabry, E. (2002). Comparing student satisfaction with distance education to traditional classrooms in higher education: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Distance Education, 16(2), 83-97.

Berge, A. L. (1999). Interaction in post-secondary web-based learning. Educational Technology, 18(1), 5-11.

Edelson, P. J. (1998). The organization of courses via the internet, academic aspects, interaction, evaluation, and accreditation. Educational Resources Information Center, 2-15. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED422 879).

Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Computers as mind tools for schools: Engaging critical thinking (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Merrill.

Kerka, S. Distance learning, the Internet, and the World Wide Web. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 395 214, 1996).

Palloff, R. M. and Pratt, K. (1999). Building learning communities in cyberspace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Picciano, A. G. (2002). Beyond student perceptions: Issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 21-40.

Richardson, J. C. & Swan, K. S. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 68-88.

Romiszowski, A. J. and de Haas. (1989). Computer-mediated communication for instruction: Using e-mail as a seminar. Educational Technology, 29(10), 7-14.

Romiszowski, A. J. and Jost, K. (1989, August). Computer conferencing and the distant leaner: Problems of structure and control. Paper presented at the Conference on Distance Education, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI.

Rovai, A. Alfred, (2002). A preliminary look at the structural differences of higher education classroom communities in traditional an ALN courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 41-56.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D.R., and Archer, W. (2001). Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education. Retrieved July 20, 2006, from: http://cade.athabascau.ca/vol14.2/rourke_et_al.html

Sherry, L. (1996). Issues in distance learning. International Journal of Educational Telecommunications, 1(4), 337-365.

Spiceland, J. D., and Hawkins, C. P. (2002). The impact on learning of an asynchronous active learning course format. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 68-75.

Yang, H. & Maina, F. (2004). STEP on Developing Active Learning Community for an Online Course. In C. Crawford et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference 2004 (pp. 751-760). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

About the Authors

Harrison Hao Yang, Ed.D, is a professor of educational technology at the State University of New York at Oswego, and holds an adjunct professorship at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. E-mail: hyang2@oswego.edu

Fung Chun Lau, M.Sc., M.A. (I.T.Ed), is a tutor of Statistics and Mathematics courses at The Open University of Hong Kong, and is a postgraduate of M.A. (I.T. Ed) course at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. E-mail: laufc1326@yahoo.com.hk