| March 2006 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: Advent of the Web as a low cost publishing medium has had a negative impact on educational television. There are many disciplines where distance learning and collaborative activities are best accomplished by television. MIT and its international associates provide us with some of their current experienced with teleconferences for interaction to factor into our plans for distance learning.

Connecting Distant Communities

through Video Communication Technologies

in Design Studio Workshops

Federico Casalegno and Larry Sass

Abstract

This paper focuses on the description of how to use videoconferencing to connect physically distributed communities involved in distant design workshop.

We discuss connected communities using remote collaboration communication technologies and report the results of ethnographic observations carried out during two collaborative distant design workshops held at the MIT -Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Fabricating Ceramics Class, Fall 2002: Generative and Parametric Tools for Design and Fabrication, Spring 2003. During these workshops, MIT students cooperated with other students (IST, Portugal) or with a private company (Fosters & Partners, London) in order to better achieve their design projects.

The goal of this paper is to discuss the use of videoconferencing tools in learning environments in order to improve collaboration among distant communities.

Keywords: Connected communities, video-conferencing, remote collaboration, distant communication dynamics, learning environments, interactive digital media.

Distant design workshop description

Classes

We observed two different collaborative design workshops.

[A] The workshop on Fabricating Ceramics focused on the designing process using parametric modeling and prototyping software with ceramics. The workshop was a research seminar using existing prototyping tools in new ways in order to fabricate curved surfaces of varying shape and scale with ceramic materials. The workshop’s objective was to work out a designing process, in this case with bricks or blocks, that was similar to Frank Lloyd Wright's buildings using custom made tiles, using computation as the designing generator and prototyping as our beginning and final output. The workshop had also intense online design collaboration with The Department of Engineering at The Instituto Superior Tecnico in Lisbon, Portugal. Students there mainly focused on designing, while students at MIT focused on materials and fabrication.

During the semester, the classes were divided into groups and formed mixed American-Portuguese teams. To improve the collaboration between students and between universities, the teams were composed by MIT students working with IST students. During the semester they had regular on-line collaboration sessions. Remote collaborative sessions were based either upon team-to-team collaboration or upon class-to-class collaboration, which included the entire learning community. In the team-to-team collaboration, the students were working on their own projects, communicating with their remote partners in order to achieve and improve their design project. During the class-to-class on-line collaboration students presented their works; professors could monitor the status of the design projects and give advice and critics about the following steps. Twenty students took part in the workshop: 12 from MIT and 8 from IST. If we consider the entire learning community, including faculty, teaching assistants and administrators, we have more then 40 people involved.

[B] The Generative and Parametric Tools for Design and Fabrication was a collaborative workshop with Foster and Partners (London) that explored a computationally-based, explorative approach to design. Parametric and generative design tools were combined with digital fabrication and rapid-prototyping techniques, in a cyclical process, to generate and evaluate alternative, innovative design solutions to a design problem. The design problem focused on light. 10 MIT students were involved in the workshop, and considering the entire learning community 20 people were involved in this design workshop.

In both workshops, the learning community used a complex collaborative environment, using different interactive media to collaborate and achieve their design project.

Remote collaborative learning environment communication technologies

The goal of the workshop was to use communication technologies to create a continuous space to connect remote communities for a better learning and design experience. One of the innovative aspects of these workshops is the use of different technologies, the way that the learning community collaborated in exchanging knowledge and documents, jointly working on projects and the team-to-team interaction. Here below is a description of the different media we use to connect distant communities.

StudioMIT

StudioMIT (http://studio.mit.edu) is an on-line educational environment that complements the physical studio environment; it is a Web-based platform that supports the community of students, staff, and faculty. During the semester, the learning community used Studio MIT to share files, upload and download documents, create mailing lists, interact in discussion forums, communicate and exchange project related information.

Video and Audio Conferencing

NetMeeting's audio and video conferencing features allow you to communicate with anyone on the Internet (http://www.microsoft.com/windows/NetMeeting/Features/default.ASP). This allows both parties to see and talk to each other; in the case of this collaboration, it allowed the class to present their projects, collaborate and gain valuable and immediate feedback and comments. Features in NetMeeting also include a whiteboard for simultaneously sharing documents, program sharing, and chat and file transfer.

iCom

This is an MIT-Media Lab project; it connects distant sites. Its normal mode is background, providing continuous ambient awareness between all stations, but at any time it can be transformed into a foreground mode for ad-hoc Tele-meetings or casual interaction, without the need of dialing telephone numbers or waiting for connections to be established (http://www.medialabeurope.org/hc/projects/icom/). We also used PictureTel, establishing a high quality of video conferencing.

Email and Instant messaging.

With Instant Messaging people are able to communicate via instant messages, to chat individually or in a group and send/receive pictures. The students also used email to communicate and participate in the class mailing lists or forum discussions.

Research and evaluation methodology

The research methodology we used is based on 3 complementary steps and it is part is of a wider research project on the use of digital media in education (creativity & learning with digital media: (http://www.media.mit.edu/federico~/creativity).

[1] Experts

The first step of the methodology consists of interviewing education and interactive digital media experts. These interviews drive us to investigate the relationship between interactive media and learning, especially focusing on the pedagogical issues emerging with the implementation of new collaborative learning environments and with the use of computational tools for education. This stage provides essentially a generic theoretical framework.

[2] Ethnographic observation

The second step consists of carrying out ethnographic observation during the workshops, observing students and on-going pedagogical activities. Throughout the class and the online and face-to-face collaboration, I took notes and annotate all kinds of information gathered by observing the learning community work in progress. On the other side, I had access to all the students’ work through the Studio MIT on-line collaborative platform, or accessing the mailing list where the learning community discussed not only about the logistics of the class but also about the social dynamics and the collective works that the class was doing.

[3] One-to-one interviews

The last step consisted in doing one-to-one interviews with all the students involved in the class, using a qualitative research methodology. These interviews took place in a face-to-face situation (Boston, Lisbon and London) and I followed the same interview grid with all the students. The interviews’ content has been divided into categories, classified and analysed. I interviewed the entire learning community members at the MIT in Boston, at the IST in Lisbon and at Fosters and Partners in London

Design Exchange at a Distance

Design studio

The definition of a design studio dates back as far as 1823 with methods of teaching with a strict focus on classical design. The school was composed by four stages of learning leading to the designation of a diploma of architecture. [1] The makeup of the Ecole has been transferred to the US by William Ware to the halls of MIT in the late 1860s [2]. The typical MIT studio environment for architects is an open space where students design in groups, where students glance over a desk at fellow students work or exchange comments through late night interactions. The open studio environment started (library). In most schools that environment continues as a model of collaborative learning environments. Now, thanks to new communication technologies, we connect distant learning environments, creating learning connected communities that learn, work and interact from distant places. In that context, a major issue within design studios is to form effective learning communities and to use communication technologies that improve their capabilities. Video communication tools help create stronger connected communities and enormously expand their ability to create and work jointly.

Audiovisual technologies for education

Television and audiovisual techniques for educational purposes have been introduced in the mid fifties [3]; since then, the evolution and the variety of these technologies increased enormously and the debate concerning the pedagogical use of audiovisual techniques for better educational results is still very open. Those techniques are important for two main reasons: the first one considers the fact that audiovisual techniques allow knowledge transmission and effective information sharing. From a media theory point of view, J. Mayrowitz [4] showed the importance of the introduction of television in educational settings, and of creating a common cultural background between spread communities. From a psychological point of view, D. Kerkchove [5] pointed out how audiovisual techniques deeply influence our cognitive thinking models. From a communication and design point of view, Steve Wittaker [6] studies the implications of using audiovisual technologies for interpersonal communication. The second main reason is that those techniques efficiently improve the collaboration between distant communities. Audiovisual technologies are crucial in the educational process because they are at the crossroad between the exchange of information among communities and their ability to process, assimilate and transform it into knowledge [7]. Moreover, these technologies have an enormous impact on connecting distant communities. Hereafter we are interested in reporting our experience in using audiovisual technologies to connect communities and to improve distant design.

Using videoconferencing in design projects to connect communities

In distant design projects, videoconferencing technologies were mainly used in four complementary ways in order to: lecture at a distance, discuss ongoing projects, allow team-to-team collaboration and, finally, to provide video-cafes and common meeting places for students. These modalities of using video communication technologies foster the emerging of an active learning connected community.

Lectures at a distance and import critics’ expertise

In this case videoconferencing was mainly used to transmit knowledge thus favoring forms of distant teaching and learning. Distant universities could benefit from remote professors in an effective way. Lessons were given from one university to the other in order to create a common knowledge background and to allow different communities of students to share the same level of knowledge and to have the same intellectual tools to work on their design projects.

Fig. 1: Distant teaching in studio environments

Secondly, critics from remote experts enriched the team’s works. Thanks to audiovisual techniques, students could present their work to critics and benefit from their comments and remarks. Learning from experts at a distance where practitioners teach their specialty in studio, anywhere studio happens, is a very important aspect of the use of audiovisual techniques.

|  |

Figs. 2, 3: Students present and discuss with remote experts in London

Project based group discussion

Project teams regularly presented their works to the entire learning community (including professors, students and invited experts), updating all the members on the state of the art of their projects and favoring exchanges and critics between the various communities.

Fig. 4: Cross presentation between MIT and IST.

Team-to-team collaboration.

Each small team used the videoconferencing techniques to cooperate with their distant team, to create, comment and discuss their on going projects in a regular basis.

Fig. 5: Team-to-team collaboration.

Fig. 6: Team-to-team collaboration, students sharing sketches.

Video Cafes and common meeting places

It’s very important to have strong ties among community members to improve learning community dynamics. In order to do so, and to develop social capital, mutual trust and to better know each-other, students used videoconferencing systems to chat about non educational issues and mostly focusing to simply getting to know each other, to converse about cultural differences, common hobbies and other topics that improved the community cohesion.

Using videoconferencing in these four different settings allowed us to create a video mediated environment and to provide an efficient technological setting for different modalities of communication. At the same time, this allowed us to foster communication and practice, transforming two separated groups of students into an efficient community of practice. With this methodology, distant communities could interact on aspects related to their design projects and remotely work together in common design projects, but they could also discuss and chat on all kind of topics.

Videoconferencing was the first modality we used and it allowed us to transmit knowledge from the top level of the learning community, from professor to students. It was the most formal modality of interaction, but it was fundamental, from a content point of view, to create a common knowledge background and, from a logistic aspect, to organize the workflow among distant communities.

The second modality was important because it forced each group to systematically produce some sort of sharable artifacts to discuss with the entire learning community.

We designed our learning environments to foster what Seymour Papert [8] defines as constructionism: “[Constructionism] … attaches special importance to the role of constructions in the world as a support for those in the head, thereby becoming less of a purely mentalist doctrine. It also takes the idea of constructing in the head more seriously by recognizing more than one kind of construction (some of them as fare as removed from simple building as cultivating a garden), and by asking questions about the methods and material used” (S. Papert, 1993, p. 143). S. Papert emphasizes the importance of externalised, socially sharable entities, artefacts or objects in the learning process. Learning process is based on the internalisation of the external information and by the externalisation of internal information, in a cyclic perpetual dynamic. This is the way we structured the learning process: students had weekly assignments that they had to work on, print 3D artefacts and construct models that they had to share and comment with the entire learning community. The use of audiovisual techniques is in this case fundamental because it obliges the entire learning communities to work on sharable artefacts that they can talk about during the videoconferences.

The third modality in which we used audiovisual techniques was characterized by a more informal interaction where communication was work related, improving the exchange and the implementation of ideas into design project. As J. S. Brown and P. Duguid point out, “ … the talk and the work, the communication and the practice are inseparable. The talk made the work intelligible, and the work made the talk intelligible. As part of this common work-and-talk, creating, learning, sharing, and using knowledge appear almost indivisible. Conversely, talk without the work, communication without practice is if not unintelligible, at least unusable. Become a member of a community, engage in its practices, and you can acquire and make use of its knowledge and information. Remain an outsider, and these will remain indigestible1”.

The last modality was very important in order to develop social ties among distant communities. Conversation about non-project related topics reinforced the construction of stronger social ties among distant communities. It is an efficient way for people to share experiences and we observed a direct proportional relationship between the success in designing innovative projects and the amount of non-project related conversations. Moreover, the continuous video linking was a success for the studio interaction during reviews and non-reviews times. Socialization was just as much a part of the learning and collaboration process as design exchange. Students spent many hours on personal exchange before discussing their design projects.

As in a physical design studio situation, people mix socialization times at the cafés and working times at the desk with socialization times at the desk and working times at the cafés, we fostered the same kind of dynamics using multimode kind of interaction also through video connection. The synergic combination and the parallel use of these four videoconferencing modalities provoked a very important result. We provided the students and the entire learning community a multimode communication visual channel for remote interaction: they used it in multiple ways thus creating a real space for connected communities remote collaboration. Thanks to this multimode videoconferencing they filled a place with human interaction creating a living space for learning.

Social Capital, gaze and object oriented talk

Social Capital

Audiovisual tools, and the communication dynamics that derives from the implementation of those tools in the educational environments, allowed distant communities involved in the workshop to build social capital and increase mutual trust: this is an important as well a fundamental condition to perform collaborative distant design projects [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. First of all, interacting through video transforms a distant individual into a real person. When people see their partners during videoconferencing they become “real” people, as one of the interviewed students pointed out: “The visual more about a social use... I mean we could see them, so they became real people… I think it was most useful if we were showing them some sketches, so they can understand what’s going on…”. Media are useful to provide different type of interaction: some are more suitable for transmitting strategic-oriented information and others are more suitable for favoring socialization processes. And both are necessary. Videoconferencing is a very important tool for socializing: “I think it was really important because I feel it made me connected with people particularly since we spend so much time on a computer for instant messages and email, I get a lot of mail from people I’ve never seen … I felt like when we started meeting with them over NetMeeting, it started to be more personal, so I felt like the visual part was really helpful”.

Secondly, a relevant remark on the social capital building dynamics, not related to video-collaboration, concerns the physical meetings. In fact, one of the most relevant aspects of the social capital community building is that communities, to develop social capital, have to meet physically and independently from their purposes. It is during the co-presence interaction that people build mutual trust and social capital. For our workshop, one of the key issues to foster the building dynamics of the community was the face-to-face interaction among participants. Workshops participants met at least one time during their design projects. This element helped in a very consistent way the construction of social ties among people, transforming a group of spread students into a connected community For example, the travel to London solidified internal relationships among MIT community but also the external relationship with the entire learning community. In this case, the visit was necessary to obtain important strategic information for the design projects but also to playfully socialize. The synergy between these two dimensions created an experiential community and created the connected learning community.

Another very important element to understand the building of social ties among the community is that what created a solid ties among community members' is not the structural elements but, on the contrary, the shared experience. For instance, some of the MIT students were Portuguese native speakers. A first hypothesis we had is that Portuguese MIT speaking students would be more reliable and they would help build community ties with IST students. This did not happen because what students were looking for, and what helped the community construction dynamics, was a mixture of conversation on everyday life and design project, socializing and working. In this sense, American students were playfully discussing with Portuguese students, trying to understand another language and another culture, and vice-versa. This was an element that helped to mix socialization and work, and that constructed an experience-based connected community.

It is because we used so extensively multiple modalities of videoconferencing, in a relatively short period, that two distant communities who didn’t know each other before starting the collaboration started to socialize and increased their social capital Social capital is important to successfully achieve distant design projects between remote communities.

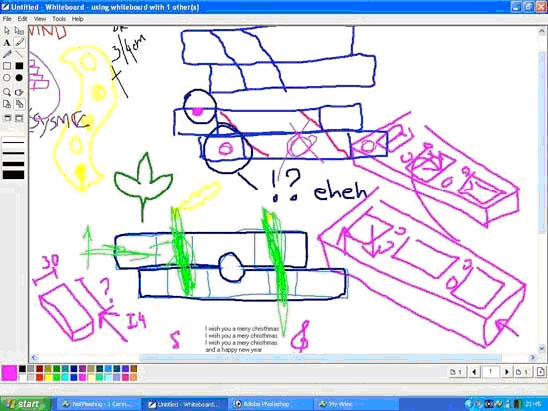

Fig. 7: Students collaborating and jointly working in the same document

with on-line videoconferencing.

Fig.8: Students commonly working in their design projects and, in the same documents, making fun and adding personal communication.

Gaze and object oriented talk

A relevant issue about people involved in collaborative processes through videoconferences is the way people look at each other and how we design workspace with interactive audiovisual technologies. Bell Laboratories carried out the very first studies on the impact of visual perception during videoconferences [14] and since then research on the field grows. As a matter of fact, according to where the two speakers are looking at, you have a more or less important impact in the collaboration processes mediated by videoconferences [15]. From the empirical research, it also emerges that gaze and the perception of it by the others is so important that even when we are not sure whether the other is actually looking at us, we think that our interlocutor is looking us in the eyes. During face-to-face conversation it is fundamental to cross our gazes because it favors collaboration. To this extent the Snap to contact theory suggests [15, p.54] that people cannot always judge gaze direction accurately and they will bias their perception toward contact unless they are certain that the looker is not looking at them. Latest research on this topic show that in a collaborative design process, more than focusing on the mutual feedback that the participants send each other during the video-communication interaction, it’s important that they first socialize and, second, they use the videoconferencing to focus on the “object” they are discussing more than trying to capture each other’s visual signs, gaze and posture to decrypt the meaning of the conversation. In our case, the workspace and the shared “object” that students were working on were the main focus during the video conferencing. Participants, while working on their design project, focused on their work rather than in their visual expression or gaze. As Whittaker points out [16], in videoconferencing the speech alone is often sufficient for effective conversation, visual information about objects is generally more valuable than visual information about work participants. These two conclusions bring him to suggest the failure of current technologies to support talk about objects, arguing that these technologies need to be better integrated with existing communication applications. Also Kraut at al., Luff et al. [17, 18] explore the “objects, not participants” hypothesis, showing how research have focused so far on the “talking heads” communication dynamics rather than exploring the talk about objects during the video conferencing interaction.

Fig.9: Students sharing and discussing printed 3D models.

In our design workshop the sharing of artifacts that happens both in synchronous mode, when students accomplish their assignments and discuss through video conferences their artifact – PowerPoint documents, 3D models, computer models – and in asynchronous mode, when they posted in the Studio MIT on-line environments their work [19], was crucial. This also fosters the creative design process: students used to think about a possible design solution, discuss it, build an artifact, and share it with the learning community, playing with their ideas and deconstructing the artifact. And they started again this process of creating, sharing, deconstructing, storing and starting again. This creative process continuously generates new artifacts that can be shared, discussed and stored thanks to new communication technologies and media environments. This creative model has been studied by Finke, Ward and Smith [20], that proposed two related but distinct phases in the process of creativity: the generative process, where people create the project’s structures, and the exploratory process, where people deconstruct these structures and play and brainstorm with ideas in order to generate the creative results. Though the videoconferences and the class dynamics we fostered these process.

Fig. 10: Students sharing objects and discussing.

Fig. 11: Sharing documents and distant messaging.

Sharing context and content

The importance of the “object and not participants” paradigm in the video conferencing doesn’t have to hide the importance of the shared context during the interactions. Firstly, Kraut et al. [21] showed that having the shared visual space helps collaborators understand the current state of their task and enables them to communicate and ground their conversations efficiently. These processes are associated with faster and better task performance. Delaying the visual update in the space reduces benefits and degrades performance. Also Steve Wittakher [6] stresses the importance of a “shared context” in order to make a remote interpersonal communication effective. According to him, the shared context can be a linguistic or a physical context. The video, in order to contribute to this process, must give us information about (1) the object we are discussing and (2) the person who is communicating. He shows how technological work has focused on one specific function of visual information, to support non-verbal communication and neglected functions such as using visual information to initiate communication or depict shared work objects. According to the non-verbal communication hypothesis, visual information is also useful in order to coordinate collaborative process. Moreover, accordingly to the idea of situatedness, the interaction between the designer and the environment strongly determines the course of designing. This idea comes from Dewey’s works [22], and it is summarized by J. Gero as “where you are when you do what you do matters” [23]. In new learning collaborative mediated environments, interactive video technologies create new shared environments between distant communities; this influence the design process. According to this view, technologies that do not support non verbal communication are inadequate to favor collaboration between distant communities in technologically mediate environments. On the contrary, all the technologies that give information about facial expressions, gaze and postures of the participants help interpersonal communications. Technology as iCom that are conceived expressly to improve chance encounters and to connect places through permanent visual connections help distant communities create a shared context and increase the sense of awareness. This helps the distant design process.

Digital Fabrication and the Exchange of Design Artifacts

S.F. Russel, R. Kraut J. Siegel [24] speak of Grounding referring to the interactive process by which communicators exchange evidence about what they do or do not understand over the course of a conversation, as they accrue common ground. They underline three important points to successfully perform conversational subtasks, and they mention that interlocutors (a) they must identify what their partners are attending to, in order to determine whether an object is part of their joint focus of attention; (b) they must monitor their partner's level of comprehension, so that they may expand or clarify their utterances if necessary; and (c) they must strive for efficiency in message formulation by constructing their utterances in accordance with Gricean norms for informativeness, brevity, and the like. During the distant design process visual tools are very important to establish a common culture, especially in remote environments. As stated by an interviewed student, “… even if it’s not easy for me as an international student sometimes to describe like designer static or the form or shape because that kind of descriptive language is not easy for me to articulate but it’s much easier to draw it and show them and then as soon as you see the drawing you understand what this person is trying to do, so one time we had a session with those two people in Portugal who had the same program on their computer and so we sketched and then we showed them and then they just sketched back, so like that kind of communication, visual tool it was really much more helpful!” So visual tools are very important because they give clues of the other team environments as well as clues of the person they are collaborating with (the way people dress, move, talk, make gesture). On the other side, they allow people to jointly work in real time on the same documents, co-creating and exchanging information, comments and feedback on the projects. For many of the students, these visual inputs during the collaboration considerably increased the ties and the cohesion between teams giving the sense of working together.

Moreover, it is fundamental to stress the importance of working together, with “objects” that students mutually manipulate with an innovative communication system that creates a real new communication dynamics. The hypothesis of the object-not-participants underlines the importance of creating a space for communication and not a place for communication. A space where communities collaborate and communicate.

Conclusions

Multimode videoconference system

What made our design workshop successful was the combination of different videoconference modalities. One modality was more incline to make the socialization processes affective, bringing participants to better know each-other and socialize, increasing the social capital within the learning community. The other videoconferences modalities allowed the remote interaction among participants to focus on shared artifacts and objects, increasing the creative process and allowing students to achieve their design goals. Videoconference tools allow at the same time a dynamics for communication and socialization and a dynamics to discuss work-related and design related topics. First, the synthesis of these two dynamics creates the real richness of the use of multimode videoconferences in educational setting. Secondly, this synthesis creates a real space for interaction and learning, transforming a distant group of people into a connected community. The learning community that emerged from this project is an experiential community: it is not true to say that the design project is a pretext for socialization, or that the socialization is a pretext to accomplish a design work but two dimensions are one the complement of the other. Socialization communication dynamics and communication for working related aspects are strictly correlated and inextricable and create a performing connected community. Sociality and talking about work create the community even in such a short period of interaction and in a geographically distant setting. A community is not sustainable if structured on a communication merely based on work related topics. Likewise, a community is not sustainable if it is exclusively based on socialization a-finalized communication dynamics. In our workshops, videoconferencing technologies, mixing these two dimensions created a successful connected learning community.

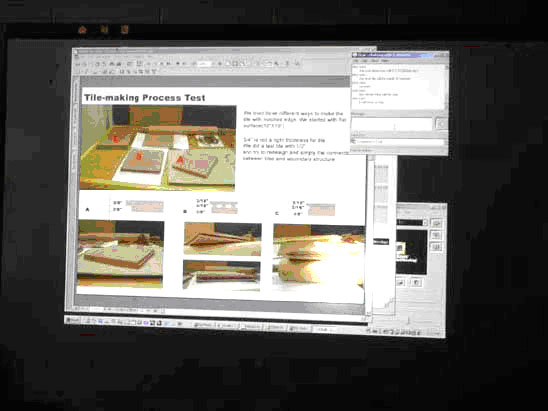

Evaluation

The final review, that also happens through video-conferencing illustrates the positive results of the distant design workshops. The evaluation of the design projects was, generally speaking, very positive: the teams accomplished their design projects successfully and had positive academics notes. The final interviews with students demonstrate that 75% of them were more than satisfied about the implementation of the media environment and the use of videoconferencing for their design projects. 25% of the students who didn’t appreciate the videoconferencing tools made up for the minority of the community that used the communication tools only to discuss working and design related topics. They didn’t make any effort to discuss about non-design related topics, or they simply didn’t look for it. Failing to find other common territory for discussion affected the results of the design projects and the community building dynamics.

Fig. 12: Final Presentation

Fig. 13: Final Presentation.

Creating a real space for community interaction

One of the key success elements for these workshops is that we considered that the videoconferences were situated in different places and we had to provide not a mere place for connections but a space for interaction. If in the physical place people interact in multiple ways, we also wanted to provide multiple ways of videoconferencing so people could use the same multimode way to communicate, but taking advantages from the technological tools. In this sense, we worked in order to use the communication efficiently, and not to simply sustain the communication among students. Thanks to interactive media, we fostered the creation of a real space for interaction: to obtain this, we provided a media environment where people could “bring” their own experiential world into the project, transcending the specific functional space. Because people can use videoconferencing to talk simultaneously about their own project and personal life, they became a community that managed to efficiently achieve their design projects.

References

[1] Robin Middleton (ed) The Beaux-Arts and nineteenth-century French architecture, London, Thames and Hudson, 1982.

[2] John Andrew Chewning, William Robert Ware and the beginnings of architectural education in the United States, 1861-1881. Published c1986. MIT Ph.D. Thesis Arch, 1986. http://architecture.mit.edu/htc/research/degree_phd.html

[3] Newsom, C.V. and Hungerford, A., A television policy for education: Proceedings of the Television Programs Institute held under the auspices of the American Council on Education at Pennsylvania State College, April 21–24, 1952. Washington: American Council on Education, 1952.

[4] Meyrowitz, Joshua, No sense of Place. The impact of electronic media in social behaviour, Oxford University Press, May 1986.

[5] De Kerckhove, Derrick, Brainframe: technology, mind and business, Utrecht, Netherlands, Bosh & Keuning, 1991.

[6] Steve Witthaker, Rethinking video as technology for interpersonal communication: theory and design implications, International Journal of Human Computer Study, Vol. 42, Issue 5, 1995.

[7] Brown, J.S., Duguid, P., The social life of information, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, USA, 2000.

[8] Papert, Seymour, The Children’s machine, Basic Books p. 143, 1993.

[9] Coleman, James S.: Social Capital in the creation of human capital, University of Chicago, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 94

[10] Putnam, Robert, Bowling Alone. Simon and Schuster, New York, NY, 2000

[11] Preece, J. (Ed.) (2002) Supporting Community and Building Social Capital. Special edition of Communications of the ACM, 45, 4. 37-39

[12] Will Allen, Margaret Kilvington, Garth Harmsworth, and Chrys Horn, The role of social capital in collaborative learning, Nov. 2001 http://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/research/social/social_capital.asp

[13] Wellman, Barry, Anabel Quan-Haase, Jeffrey Boase, and Wenhong Chen, Examining the Internet in Everyday Life, http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~wellman/publications/euricom/Examinig-Euricom.htm

[14] R. Stokes. Human Factors and Appearance Design, Consideration of Mod II PicturePhone Station Set. IEEE Transactions on Communication Technology, p.318-323, 1969.

[15] Milton Chen, Gaze: Leveraging the asymmetric sensitivity of eye contact for videoconference, April 2002, Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems: Changing our world, changing ourselves, Letters CHI, April 2002, Vol. No 4, Issue No 1.

[16] Whittaker, Steve, Running head: things to talk about, http://dis.shef.ac.uk/stevewhittaker/talking_about_things.pdf

[17] Kraut, R. E., Miller, M. D. & Siegel, J. (1996). Collaboration in Performance of Physical Tasks: Effects on Outcomes and Communication. Proceedings, Computer Supported Cooperative Work Conference, CSCW'96, 57-66. New York: ACM Press.

[18] Luff, P., Heath, C., Greatbatch, D. (1992). Tasks-in-Interaction: Paper and Screen Based Documentation in Collaborative Activity, In Proceedings of Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work: 163-170. New York, ACM.

[19] Leonard, Jim, Classroom and Support Innovation Using IP Video and Data Collaboration Techniques, CITC4’03, October 16–18, 2003, Lafayette, Indiana, USA.

[20] Finke, R. A., Ward, T. B. and Smith, S. M. (1992). Creative Cognition -Theory, Research, and Applications, Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press.

[21] Robert E. Kraut, Darren Gergle, Susan R. Fussell, The Use of Visual Information in Shared Visual Spaces: Informing the Development of Virtual Co-Presence, CSCW’02, November 16—20, 2002, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

[22] Dewey, J. The reflex arc concept in psychology, Psychological Review, 3, (1896 reprinted in 1981), 357-370.

[23] John S Gero Computational Models of Creative Designing Based on Situated Cognition, C&C'02, October 14-16, 2002, Loughborough, Leic, United Kingdom

[24] Susan R. Fussell, Robert E. Kraut, Jane Siegel, Coordination of communication: effects of shared visual context on collaborative work, December 2000, Proceedings of the 2000 ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work

______________________

1. Brown, J.S., Duguid, P., 2000, Chapter V, community support. See also Orr Julian, Talking about machines: an ethnography of a modern job, IRL Press, Ithaca, NY

About the Authors

Federico Casalegno, Ph.D. is a Research Scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab

Email: federico@media.mit.edu

Larry Sass, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department Of Architecture

Email: lsass@mit.edu