| March 2006 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: This study test three e-learning strategies based psychological theories of learning. A prior analysis shows a variety of factors influence learning; the research design compares implementation based behaviourist, cognitivist, and constructivist learning theories.

The Impact of an E-Learning Strategy

on Pedagogical Aspects

Felix Mödritscher

Abstract

Planning and implementing courses – no matter whether done for face-to-face education or within e-learning environments – deal a lot with pedagogical issues. Learning is influenced by factors such as attention, motivation, and emotions as well as by learner characteristics like prior knowledge, cognitive and learning styles, intellectual capabilities and constitutional states. This paper examines learner-centred aspects of e-learning by drawing conclusions from traditional learning in the classroom situation and outlining implications for the process of virtual learning. Furthermore, a case study carried out in the field of adult education tries to point out findings on the impact of different e-learning strategies on the factors influencing learning.

Keywords: pedagogical aspects of e-learning, factors influencing learning, learner characteristics, impact of e-learning strategy, virtual learning, case study.

Introduction

E-learning can be considered to be highly related to learning and teaching as stated in (Jain et al., 2002). Therefore, pedagogy and didactic are important aspects for all facets of e-learning, reaching from the creation of the courseware to application of an e-learning system to the evaluation of the learning progress. (Mödritscher et al., 2006) showed an online course for a certain topic may be implemented in various ways and each method differs in aspects of the teaching process such as the instructional design, effort for the teacher, effectiveness of the teaching strategy, or e-learning platform (in this case the platform used was Moodle).

In this paper, relevant factors of the learning process such as attention, motivation, emotional aspects, and students’ characteristics are examined according to different e-learning strategies. Therefore, section 0 derives relevant theoretical aspects for the virtual learning process by examining knowledge transfer within the classroom situation. In the following, section 0 describes the case study about implementing different e-learning strategies, which was carried out at the Graz University of Applied Sciences CAMPUS 02 (Campus02, 2006). In section 0 findings on pedagogical aspects in relation with these e-learning strategies are highlighted.

Pedagogical Aspects of Learning and Implications for E-Learning

Education can be understood as “activity undertaken or initiated by one or more agents that is designed to effect changes in the knowledge, skill, and attitudes of individuals, groups, or communities” (Knowles et al., 1998). In contrary, the term “learning” emphasises the person in whom the change occurs or is expected to occur. Thus, learning comprises “the act or process by which behavioural change, knowledge, skills, and attitudes are acquired” (Boyd et al., 1980). Tying up to this definition, the following subsections deal with the learner-centred aspects of the traditional learning process –relevant factors for learning, characteristics of learners, and further influences on learning – and examine them within the context of e-learning.

Factors Relevant for the Learning Process

Drawing conclusions from (Bransford et al. 2000), four factors significantly impact the learning process: (1) attention, (2) motivation, (3) emotions, and (4) experiences of the learner.

Focus of attention determines if a student mentally follows a lecture and, therefore, the degree of behavioural change. E-learning requires a strategy for getting and keeping the learner’s attention. It is necessary to consider cognitive processes such as the learner’s selection of incoming data into the sensory memory, organising and integrating this information by building connections in short-term memory and encoding it by transferring it to long-term memory. Thus, it is recommended to apply certain principles for instructional design (Fleming & Levie, 1993).

Motivational states of students are of importance for stimuli given by the teacher to promote the learning process. (Bransford et al., 2000) state that “motivation affects the amount of time that people are willing to devote to learning”. Yet, this willingness to learn results from different motives beginning with the intention to achieve something, competing against colleagues, helping other people, or emotional factors like anxiety. (Entwistle, 1981) classified three motivational orientation styles: (a) meaning-oriented, (b) reproducing-oriented, and (b) achieving-oriented motives. Motivational aspects for

e-learning may also depend on learning content, pointing out the relevance for an instruction or including interactive elements such as games and simulations. Furthermore, it is advantageous to create competition within a learner group and adapt to pre-knowledge in the subject domain to prevent the students from being under challenged. For instance, (Astleitner & Keller, 1995) describe a framework for adapting instruction to the learner’s motivational state in computer-assisted instructional environments.Emotions, similar to motivation, have a strong impact on the learning process.

(Tobias, 1987) points to findings on students’ performance depending on anxiety, in particular test anxiety, and proposes special methods for dealing with such problems. On the other hand, an emotion – whether negative and positive one – may influence learning due to its special nature. With respect to (Paulsen, 2005), “emotion is an unconscious arousal system that alerts us to potential danger and opportunities”. Thus, addressing a learner’s emotional channel can be seen as a key cognitive process for transferring data into the short- or even long-time memory. Within e-learning, the improvement of the learning process can be realised through emotions by storytelling, empathy, provocations, emotional figures and animations, and group works, enabling confidence in the learning content.Knowledge transfer can be improved if learners relate prior knowledge either in the same domain or in a similar context. (Anderson, 1995) states that “interference happens, when information gets mixed up with, or pushed aside by, other information”. At the beginning, the degree of mastery of the original subject influences the learning process (Bransford et al., 2000). In particular, an adequate level of initial learning is required. Then, learners can construct new understandings by tying up to previous experiences. In this way, learners become capable of understanding conceptual changes, adopt knowledge regarding their culture or everyday life, and even improve meta-cognitive abilities. Research findings have shown that the higher the level of prior achievement within a domain or a context, the less instructional support is required to accomplish a task (e.g. Tobias & Ingber, 1976). Referring to (Tobias, 1994), prior knowledge strongly relates to interest in the subject. Considering prior knowledge within online courses, the macro-adaptive instructional approach described in (Park & Lee, 2004) deals with the necessity to determine learning objectives, define dependencies between instructional units and assess the students’ competencies to grant access to restricted instructions. These aspects are highly dependent on the learning content so that well-established e-learning standards – such as the specifications of SCORM (ADL, 2004) – fulfil these requirements.

Learner Characteristics

Individual differences have a strong impact on learning (Cronbach, 1957). According to literature, learners differ from each other in learner characteristics:

Intellectual capabilities exhibit a unique profile for each learner that can be characterised by Multiple Intelligences (Gardner, 1993) or cognitive abilities (Snow, 1986). Education deals with the theory of multiple intelligences in two ways: On one side, teachers devise curricula addressing different intellectual capabilities. On the other side, educators focus on development of specific intelligences such as intra- or inter-personal skills. Although it is difficult to consider each learners’ intellectual abilities within the typical classroom or e-learning situation, (Kelly & Tangney, 2003) applied Gardner’s theory within an intelligent tutoring system named EDUCE.

Learning preferences are influenced by context and predispositions or orientations to learning (Jarvis & Woodrow, 2001). Preferences can be classified in four different areas: (a) environmental, (b) emotional, (c) sociological, and (d) physical (Dunn et al., 1989). Preferences are considered in e-learning environments in various ways such as adapting language, presentation of learning content, and group models (Brusilovsky, 1996).

Cognitive and learning styles are related to intellectual capabilities and preferences to provide practical models for teachers. Cognitive styles, such as field-dependence, reflectivity versus impulsivity, haptic versus visual, and the forth, characterise modes of perceiving, remembering, thinking and decision making. Learning styles like holist versus serialist, perception styles, and concept formation approaches, describe the connection between instructional presentation and materials with a student’s preferences and needs (Schmeck, 1988). Practical models like the WAVI model by (Riding, 1991), the AdeLE project (AdeLE, 2006), learning styles (Kolb, 1984), and the AHA! System (Stash et al., 2004), have been developed.

Constitutional attributes and states of learners involve physical properties of the body like disability, age, and amblyopia as well as short-term conditions such as tiredness, concentration, emotional and motivational states (Mödritscher et al., 2004). These factors are well-documented; for instance disabilities as stated in (Sànchez & Flores, 2004) and constitutional states of learners such as learner attention (Ueno, 2004).

Self-efficacy and meta-cognition influence the learner achievement (Bandura, 1982). Self-efficacy comprises a student’s evaluation of the ability to perform a given task through different senses. Meta-cognition stands for the awareness of the process of learning and consists of two basic processes: (a) monitoring the learning process and (b) adapting the learning strategy (Winn & Snyder, 1996). According to (Park & Lee, 2004), meta-cognitive abilities examined by various researchers within the area of aptitude-treatment interaction (ATI) are highly related to the learners’ experiences and have an impact on different variables, such as the degree of feedback and tutoring, the locus of control, and personality attributes. In particular, various systems in the scope of adaptive hypermedia, as with methods like adaptive navigation support, focus on learner control (Brusilovsky, 1996).

Background knowledge of a learner comprise language and computer skills as well as experience in a related situations and contexts. The impact on learning is illustrated by reports that students from abroad have problems understanding the language (Campbell et al., 2004), and these are connected to learning styles s. (Felder & Henriques, 1995) Thus, (Mödritscher et al., 2005) suggest providing translations for problematic phrases to support the learning process. Various approaches in e-learning focus on experience in work related areas, the user’s profession, experience with the learning platform (Brusilovsky, 1996), and foreign language students (EPHRAS, 2005). The INCENSE system offers the ability of identify and analyse different learning situations and, if necessary, automatically switching among them(Akhras & Self, 2000).

Prior knowledge and experience in the domain is the last and most relevant characteristic of learners. (Vassileva, 1996) differentiates between experience and real knowledge about a topic, where experience determines the user’s model of a knowledge space, the way of browsing through and mastering tasks in a domain, etc. Similarly, (Bransford et al., 2000) state that people having developed expertise in a particular area are able to think effectively about problems in this area and, therefore, differ from novices. Both factors are relevant for the learning process as shown in the last section. Thus, most theoretical models – e.g. the macro-adaptive instructional approach dealing with adaptation of the learning process according to the student’s pre-knowledge and dependencies between instructional units (Park & Lee, 2004) – and systems – like AHA, ELM-ART, INTERBOOK, KBS, PT, and the forth (Henze, 2000) – focus on the prior knowledge of a learner. Experience is considered within the field of various research fields such as adaptive hypermedia, e.g. by methods like adaptive navigational support for browsing through a hyperspace (Brusilovsky, 1996).

Based on these seven classes of learner characteristics, it is clear that the result of learning is highly dependent of the individual learner. Therefore, teachers, e-learning content creators and online instructors have to know pedagogical aspects and provide alternate methods to support different learner needs. Additional factors influence learning as shown in the upcoming section.

Further Influences on Learning

The previous section dealt with learner-dependent attributes that affect the learning process. Further aspects – given by didactics or related to learner characteristics – may influence learning.

Referring to (Krapp et al., 1992), interest in a certain domain depends on aspects of prior knowledge, emotions, and motivation as discussed earlier. It is assumed that interest is derived from expertise and positive experiences that enhance the learner’s self-confidence. When supported by a didactical strategy, e-learning can adapt to support the interest factor. For example, the learner may be allowed to choose preferred learning content, or this can be derived by statistical methods from learner responses, taxonomies and IR-based strategies. Learning management systems may focus on motivation or prior knowledge, or self-organising hypertext maps like the KnowledgeSea (Brusilovsky & Rizzo, 2002) or environments supporting constructivist learning that navigate course concepts (Mödritscher et al., 2005).

A didactical key issue is about remembering and forgetting. While these processes are highly related with intellectual capabilities, meta-cognition, prior knowledge and motivation of learners, a teacher might antagonise the forgetting curve (Ebbinghaus, 1964) by regularly repeating relevant content. To define such key concepts within a course, teachers choose learning objectives, appropriate teaching strategies, e-learning environments and specific learning content. Examples include typical concepts with a macro-adaptive instructional approach (Park & Lee, 2004), competency-driven strategies realised in the study introduced in this paper, and options for instructional sequencing within the specifications of SCORM (ADL, 2004).

Another didactical aspect is time to learn or the so-called time on-task. (Bransford et al., 2000) point out the necessity to give the student enough time to reach an appropriate level of experience within the scope of a certain domain, especially for a complex subject matter. Nevertheless, learners are often faced with a situation in which a teacher tries to “cover” too many topics too quickly, which hinders effective knowledge transfer for different reasons. On the other hand, time on-task should be limited so that the learner is sufficiently challenged and self-efficiency is able to increase. It is particularly important for e-learning to plan the time allocated for learning and the time really spent on learning. As pointed out in (Dietinger, 2003), one advantage of e-learning is that learners can go through course materials at their own pace. Deadlines must be set realistic in order not to frustrate students. Ability to define and manage deadlines for instructional units is provided by commonly known specifications for e-learning content and learning management systems, even by open source solutions such as Moodle (Moodle.org, 2006).

Depending on the given learning objectives, issues like feedback and tutoring might be of relevance for the learning process. In particular, if a course aims at mediating high-level objectives, skills, or behaviour, immediate feedback is important for successful learning (Thorndike, 1913). With respect to (Park & Lee, 2004), various research areas, such as aptitude-treatment interaction or the micro-adaptive instructional approach, deal with giving feedback and provide technical solutions like intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) or techniques for natural language dialogues. Furthermore, (Mödritscher & Sindler, 2005) suggest methods such as simulations, games, automatically graded essays, and quizzes created with professional authoring software.

Finally, learning is also affected by the context in which knowledge transfer takes place. According to (Bransford et al., 2000), learners might be able to learn in a certain context, but fail to learn or transfer experiences gained to other contexts. Contextualised knowledge is used in e-learning environments such as INCENSE. As this issue is highly related to constructivist theory, new paradigms, such as application of a dynamic background library to support context-driven learning (Mödritscher et al., 2005), are import.

Concluding this section, it has to be pointed out that the issues depicted so far comprise just the most relevant and learner-centred factors of the learning process. A complete overview detailing the complexity of learning can be read in (Bransford et al., 2000). Nevertheless, it can be stated that the most critical factor for successful learning is the learner. The most important difference between the classroom situation and e-learning is that a teacher can adapt the learning process much more effectively by holding a lecture in the class, since communication in both directions – from the teacher to the learners and vice versa – is faster and more effective. It is much harder to evaluate and react to factors in the learning process or learner characteristics via e-learning platform. Nevertheless, research mainstreams such as adaptive instructional systems or adaptive e-learning (Park & Lee, 2004) are designed to deal with these aspects of adaptation in e-learning environments to improve the learning process.

To examine pedagogical issues, the next two sections report a case study implementing different e-learning strategies and examine their impact on the learning process.

Setup of the E-Learning Study

After identifying the need for realising e-learning phases within its educational concept at the Graz University of Applied Sciences CAMPUS 02 (Campus02, 2006), an internal project was initiated with the aim to support lecturers to implement their e-learning strategy within the area of adult education. The study introduced in this section is one of the project’s outcomes and describes an online course about the topic “document formats”. The course was carried out over a period of two month and realised according to a full virtual concept using a customised version of the Moodle e-learning platform.

The course was essentially a lecture on basics of information technology to teach competencies and some higher levels of objectives. Based on Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom et al., 1956), the learning objectives comprise five “Level I”, four “Level II”, and two “Level III” objectives of the cognitive domain, two “Level III” objectives of the psychomotor domain and one “Level III” objective of the affective domain. To realise different e-learning strategies, three courses were implemented and each of the 38 students was assigned to one of these courses according to the achievement levels of a prior topic-related lecture. Referring to (Mödritscher et al., 2006), the three courses can be characterised in the following ways:

Course A was planned with respect to Behaviourism. The teacher organized objectives and content into three modules. Fourteen students were assigned by the teacher to study each module and on completion, measured achievement levels using an online examination. The course included game related activities, allowing several attempts in the exam, an increasing difficulty level, a task to gain a bonus, and other interactive ways to keep learners motivated. The learning process was assessed by typical behaviourist tools like multiple-choice questions, task assignments, or short written answers. To examine the high-level objectives of the psychomotor and affective domain, ITS methods were simulated by the teacher.

Course B employed the ideas of Cognitivism. Tasks were characterised by classical cognitive elements, for instance repeating learning content in different ways, working out parts of the course within a group work or re-structuring the content. This course was divided into two phases: First, three groups consisting of four students each had to work out a part of the overall objectives. In the second phase, the groups were reassembled to four groups with three members, while each group had to restructure the results of the first phase using a WIKI environment. To motivate groups, the best work of the second phase was awarded a bonus. To assess the learning process, the results of each phase were graded by the teacher based on the quality and quantity of students’ work within the group. The WIKI environment allowed reproducing the student’s effort within the group.

Course C employed constructivistic learning realised in four groups consisting of three students with the materials and task to create a manuscript for mediating all learning objectives of the course. In the second phase, the three members of each group had to compare the works of the other groups and evaluate them by distributing a certain amount of points and reasons this distribution. Again, the group with the best work received a bonus. Group works were graded by the teacher on basis of the students’ peer reviews.

While the e-learning phase was in progress, students were instructed to document certain aspects, such as the effort for learning, a self-assessment on reaching the objectives, the learning materials used. An unannounced and challenging examination as well as a post-questionnaire was carried out in the lecture held after the e-learning experiment. Based on the whole amount of data retrieved from this e-learning experiment, the next section examines the impact of the e-learning strategy on pedagogical issues.

Findings on pedagogical Aspects

In accordance with section 2, this section deals with two issues of evaluating the e-learning study. On the one hand, selective learner characteristics are examined in two ways, for all participants and for the students of each course. On the other hand, the factors relevant for the learning process are analysed for each e-learning strategy. For both approaches, all data collected during and after the e-learning phase is exploited.

Assessing the Learner Characteristics

Findings on the learner characteristics are derived from the post-questionnaire, where the students had to evaluate and rate certain statements. As the literature manifests, students’ self-assessment of learning behaviour is often wrong and psychological tests are more reliable. The statements of this questionnaire are formulated in a way that students cannot infer the learner characteristics. Furthermore, the questionnaire was performed immediately after the e-learning phase, so that significant differences between the courses might be found. Results of the post-questionnaire concerning typical learner characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Considering prior knowledge (1) about the course’s topic, most students agreed with this statement and meant to have good experiences and knowledge within the course’s domain. This can be reasoned due to the students’ experiences from their jobs as well as to former lectures dealing with a few parts of the learning content. The even distribution across the three courses may be a result of the students’ assignment to the courses described in section 3. While the overall interest on the online course (2) is rather average, students of behaviourist e-learning strategy seem to be less interested in the topic than the other students that mastered the course with group tasks.

The students’ preferences (3a-e) underlie some surprises. First of all, students through all courses strongly dislike learning on the screen. Secondly, their attitudes towards preferring online tests to written exams differ from disagreement in course B to a slight agreement in course C. Similarly, students of course C more strongly prefer open-ended to closed questions than students of course B. Furthermore, students of the behaviourist approach are slightly negative about learning in a group, while the students of the other courses are positive. Applying interactive elements seems to be neutral and evenly distributed amongst the students of all courses.

Table 1

Results of the Post-questionnaire Concerning Learner Characteristics

(each statement rated with a number between 1 and 5 comprising the range from

“absolute disagreement” to “strong agreement”)

Self-assessment of | Overall ( EQ \O(x;¯) /σ) | Course A ( EQ \O(x;¯) /σ) | Course B ( EQ \O(x;¯) /σ) | Course C ( EQ \O(x;¯) /σ) |

1. Extensive prior knowledge about topic | 3.7/1.0 | 3.7/0.9 | 3.6/1.3 | 3.8/0.9 |

2. Interest in the course’s topic | 3.1/1.2 | 2.8/1.3 | 3.2/0.9 | 3.3/1.2 |

3a. Preferring online learning to reading printouts | 1.8/0.9 | 1.8/1.0 | 1.9/1.1 | 1.7/0.9 |

3b. Preferring online tests to written exams | 2.9/1.2 | 2.8/1.4 | 2.5/1.2 | 3.3/1.1 |

3c. Preferring open-ended to closed questions | 3.5/1.1 | 3.5/1.3 | 3.2/1.1 | 3.8/0.9 |

3d. Preferring learning within a group | 3.1/1.1 | 2.8/1.1 | 3.5/1.0 | 3.1/1.0 |

3e. Preferring interactive elements | 3.0/1.1 | 2.8/1.2 | 3.2/0.8 | 2.9/1.3 |

4a. Acquiring knowledge by typical cognitive processes (structuring, summarising) | 4.0/1.0 | 4.2/0.7 | 3.8/1.3 | 4.0/1.0 |

4b. Intensively studying complex content | 4.2/0.9 | 4.5/0.7 | 4.1/1.0 | 4.0/1.1 |

4c. Need to practice new skills | 3.9/0.9 | 4.2/0.9 | 3.9/0.6 | 3.7/1.0 |

4d. More wholist than analyser | 3.5/1.2 | 3.7/1.3 | 4.1/0.9 | 2.8/1.2 |

4e. More imager than verbaliser | 3.5/1.1 | 3.7/1.0 | 3.3/0.8 | 3.5/1.0 |

5a. Understanding background by research or questions (related to Kolb’s “converger”) | 2.9/1.0 | 3.3/1.0 | 2.7/0.9 | 2.6/1.1 |

5b. Meaning-oriented learning of important concepts (related to Kolb’s “assimilator”) | 4.4/0.7 | 4.5/0.8 | 4.6/0.5 | 4.2/0.7 |

5c. Tying up to own experiences (related to Kolb’s “diverger”) | 3.9/0.9 | 4.2/0.7 | 3.7/0.9 | 3.8/1.1 |

5d. Finding practical examples for theoretical content (related to Kolb’s “accommodator”) | 4.1/0.8 | 4.4/0.7 | 4.2/0.6 | 3.7/1.0 |

6. Easy to be motivated by game-based elements or competitions | 3.3/1.3 | 3.5/1.3 | 2.9/1.3 | 3.6/1.2 |

7. Preferring autonomous to teacher-driven learning | 3.1/1.1 | 3.2/1.2 | 3.3/0.9 | 2.7/1.2 |

Summarising the findings on cognitive styles (4a-e), the students’ ratings for the statements were rather high, which means they agreed about acquiring knowledge by typical processes or the need to practice new skills. The self-assessment of the so-called WAVI-factors outlines that students consider themselves to be more wholist and visualiser. Particularly, the wholist factor shows strong differences between course A and B to course C. Nevertheless (Phillips, 2005) states that learners are – for different reasons – not good judges of their style and that even psychological tests are not fully reliable in assessing cognitive styles.

Referring to Kolb’s learning style inventory, four questions (5a-d) focussed on evaluating the students’ learning behaviour by means of being more active or reflective in the learning process as well as thinking in a more abstract or pragmatic way. Overall, the students participating in the three courses see themselves as rather reflective learners, while there is no clear tendency for abstract or pragmatic thinking. Analysing the groups of the three courses, students of course A seem to rate their attitudes towards diverging and converging higher than the participants of the other courses. In contrary, students in course C do not consider themselves being as good accommodators as in the other courses. Generally, these results of the students’ self-assessment are unreliable due to the reasons stated above for the ratings of the WAVI-factors.

Concluding the results of the post-questionnaire, both game-based elements (6) as well as autonomous learning (7) are rated neutral by the overall class. Hence, students of course A and C are more convinced of the fact that game-based elements improve their motivational states slightly. On the other side, self-directed learning is seen much more positive in course A and B – the two courses mainly driven by the teacher – than in course C, which implemented a constructivistic approach.

Finally, it has to be stated that background knowledge was considered by the teacher in three ways: Firstly, the course was given in German, the students’ mother language. Secondly, the teacher introduced the students to the Moodle platform in the lecture, before the e-learning phase was started. Thirdly, the students attended a technology-focused study for two and a half year. Overall, the students should not have had problems with the course’s language as well as with the usage of the system. Analysing the questions about the system’s usability and the quality of the learning material, these two aspects were – excluding some problems about using the WIKI module in course B – not mentioned at all by the participants. In contrary, students stated that the Moodle platform can easily and intuitively be used.

Analysing the Factors of Learning

Considering the factors influencing the learning process (see subsections 0 and 0), two sources are of relevance for the findings of this analysis: (a) the distribution of the students’ activities, and (b) the students’ ratings of the statements of the post-questionnaire.

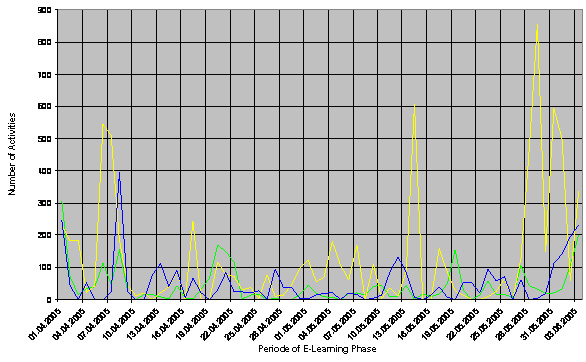

Analysing the students’ attention within the online courses, the distribution of the course activities and certain characteristics is useful, but does not cover all findings concerning attention. Particularly, it is not possible to infer something about the students’ behaviour while learning offline. Nevertheless, Table 2 (the courses’ characteristics) as well as Figure 1 (overall number of students’ activities) document that students of course B had to work much more with the Moodle system than the participants of the other courses. Interpreting the results of the concluding examination in this context, the high degree of learning within the Moodle platform does not really imply a high degree of attention, because students of course B performed worse than others. Further, several students of this course stated that the WIKI module lacks of good usability and they had to concentrate more on the tool than on the learning content. Thus, good usability of a learning management system is an important factor for a high degree of the students’ attention and adequate results in learning.

Table 2

Characteristics of three Courses based on Students’ Documentation about Learning and raw Database Queries within the Moodle System

Characteristic | Course A | Course B | Course C |

Students’ self-assessment of average effort [in h] | 12.2 | 9.4 | 7.6 |

Students’ self-assessment of mastering objectives | 92.9% | 46.8% | 74.3% |

Students’ self-assessment of the necessity for the lecturers notes | 68.8% | 31.3% | 62.1% |

Students’ self-assessment of using external material | 14.3% | 43.3% | 29% |

Students’ self-assessment of learning alone rather than in a group | 96.9% | 69.2% | 98.8% |

Results of the concluding exam | 54.8% | 37.4% | 43.2% |

Overall number of the students’ activities | 2696 | 8037 | 3162 |

Emotional states of the students can be summaries by three observations: Firstly, the instruction to upload a photo of each student as profile avatar causes a lot of activities in the discussion groups of all three courses (see lines in REF _Ref129276818 \h \* MERGEFORMAT Figure 1 around the 5th of April). Students considered this to hurt their privacy; some started emotionally driven discussion threads, while others refused to upload a valid photo.

Figure 1: Distribution of the students’ activities for the courses

A (green), B (yellow), and C (blue)

Secondly, the evaluation of course B was worse than the one of the other courses due to the usability problems and the higher effort resulting already depicted. Thus, several rather emotional comments such as “I hate e-learning”, “The task is senseless”, etc. were written down in the post-questionnaire, while students in the other two courses were not that offensive and negative. Further, the higher effort compared with the other courses was criticised (see Table 2). Thirdly, the curiosity about the learning content was rather neutral and evenly distributed over the three courses (see statement 1 in Table 3).

The students’ motivation for learning is examined by the following three findings: Firstly, in course A the deadlines (see the green line in Figure 1 around the 21st April, the 19th May, and the 2nd June) are more obvious than in the courses implementing group works (see the yellow line around the 6th May and the 2nd June as well as the blue line around the 13th May and the 2nd June). Due to the increasing activities ahead of the deadlines, it seems that a behaviouristic approach enforces students to accomplish the examination right before the module ends. Secondly, each course included some motivational elements as stated in section 0 as well as some statements about the necessity to reach the objectives. Yet, students of the courses A and C meant to master the objectives better than the participants of course B, which highly correlates with the results of the concluding exam (see Table 2). Thirdly, the motivation to complete the tasks was, according to the questionnaire’s statement 2 (see Table 3), average in course A and slightly negative in the courses B and C.

Table 3

Results of Post-questionnaire concerning the Factors relevant for Learning

(each statement rated with a number between 1 and 5 comprising

the range from “absolute disagreement” to “strong agreement”)

Self-assessment of | Overall ( EQ \O(x;¯) /σ) | Course A ( EQ \O(x;¯) /σ) | Course B ( EQ \O(x;¯) /σ) | Course C ( EQ \O(x;¯) /σ) |

1. Curiosity about learning content | 3.1/1.1 | 3.2/1.3 | 3.0/1.2 | 3.2/1.0 |

2. Strong motivation to accomplish the tasks | 2.6/1.0 | 2.9/1.0 | 2.5/1.0 | 2.4/1.1 |

Aspects of prior knowledge were already examined in the last subsection. Moreover, the teacher considered the tying up to prior knowledge by giving practical and well-known examples for theoretical learning content as well as cross-references to other lecturers. According to cognitivism, issues concerning remembering and forgetting were realised only in course B. Yet, these considerations seemed to have failed due to the bad learning results of this course. Finally, feedback and tutoring for each course differed depending on the three learning theories: While it was necessary to actively stimulate the participants’ learning in course A, students of course B required immediate feedback about the completed tasks. In course C, the teacher had to suppress any comment on the works submitted. Overall, the three courses as well as the learning outcomes differed in several aspects of the learning process as shown in this section.

Conclusions and Recommendations

To conclude this paper, I have to outline that learning is a very complex process depending of various factors and influences with each of them concerning especially the learners themselves. Thus, an instruction implementing online courses has to consider two relevant aspects: On the one side, the target group of a course needs to be analysed by means of the learner characteristics. If required, the teacher might also apply some classroom assessment methods to assess certain information about the learner within the learning process. On the other side, it is necessary to adapt the learning process towards the findings about the learners. Yet, it is not worth evaluating all characteristics, whether the effort to assess one is too high or the relevance or applicability to serve as a basis for adapting of the learning process is missing.

Summarising the study, it was shown that each e-learning strategy following one of the commonly known learning theories – the Behaviourism, the Cognitivism, and the Constructivism – is realisable for an online course within the scope of adult education. Further, each didactical strategy has a more or less strong impact on the factors influencing the learning process and the self-assessing of learner characteristics. For applying one of the e-learning strategies, it is recommended to analyse certain learner characteristics, particularly prior knowledge and motivation, to prevent the learners from failing to finish the course and to assess various characteristics to optimise the learning process. Nevertheless, there are also some didactical aspects to be considered for realising an e-learning strategy. Issues such as the impact of the learning objectives determined or the assessment strategy implemented have to be examined as part of my future work.

Acknowledgements

I have to thank my employer, the Institute for Information Systems and Computer Media (IICM) at Graz University of Technology, for arousing my interest in hypermedia and e-learning as well as the Austrian ministries BMVIT and BMBWK for founding my research work through the FHplus impulse programme. Furthermore, I have to acknowledge the support of the Graz University of Applied Sciences Campus02 for offering me competencies and the playground for this case study as well as the 38 students that had to participate in this experiment.

References

AdeLE (2006). Research project AdeLE. http://adele.fh-joanneum.at (2006-03-12).

ADL (2004). Sharable Content Object Reference Model (SCORM) 2004 2nd Edition. Advanced Distributed Learning. http://www.adlnet.org/downloads/70.cfm (2005-08-04).

Akhras, F.N., & Self, J.A. (2000). System intelligence in constructivist learning. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 11, 344–376.

Anderson, J.R. (1995). Learning and memory: An integrated approach. New York: Wiley.

Astleitner, H., & Keller, J.M. (1995). A model for motivationally adaptive computer-assisted instruction. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 27 (3), 270–280.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147.

Bloom, B.S., Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., and Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of Education Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. New York: David McKay.

Boyd, R., & Apps, J. (1980). Redefining the discipline of adult education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L. & Cocking, R.R. (2000). How people learn (expanded edition): Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Brusilovsky, P. (1996). Methods and techniques of adaptive hypermedia. User Modeling and User Adapted Interaction, 6 (2-3), 87–129.

Brusilovsky, P. & Rizzo, R. (2002). Map-based horizontal navigation in educational hypertext. Proceedings of Hypertext 2002, 1–10.

Campbell, M., Goold, A., and Goward, P. (2004). Using Online Technologies: Does Culture Matter? Proceedings of E-Learn 2004. Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 2300–2307.

Campus02 (2006). Graz University of Applied Sciences CAMPUS 02. http://www.campus02.at (2006-03-01).

Cronbach, L.J. (1957). The two disciplines of scientific psychology. American Psychologist, 12, 671–684.

Dunn, R.S., Dunn, K.J., & Price, G.E. (1989). Learning styles inventory. Lawrence, KS: Price Systems.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1964). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York: Dover.

Entwistle, N. (1981). Styles of learning and teaching. Chichester: Wiley.

EPHRAS (2005). Research project EPHRAS. http://www.ephras.org/ (2005-12-23).

Felder, R.M. & Henriques, E.R. (1995). Learning and teaching styles in foreign and second language education. Foreign Language Annals, 28 (1), 21–31.

Fleming, M., & Levie, W.H. (1993). Instructional message design: Principles from the behavioral and cognitive sciences (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice. New York: Basic Books.

Henze, N. (2000). Adaptive Hyperbooks: Adaptation for Project-based Learning Resources. Dissertation, University of Hannover, 2000.

Jain, L.C., Howlett, R.J., Ischalkaranje, N.S., & Tonfoni, G. (2002). Virtual environments for teaching & learning. Series of Innovative Intelligence, 1, preface.

Jarvis, J., & Woodrow, D. (2001). Learning preferences in relation to subjects of study of students in higher education. Proceedings of the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, 2001.

Kelly, D., & Tangney, B. (2003). A framework for using multiple intelligences in an ITS. Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 2003. Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 2423–2430.

Knowls, M.S., Holton, E.F., & Swanson, R.A. (1998). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (5th ed.). Houston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as a source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Krapp, A., Hidi, S., & Renninger, K.A. (1992). Interest, learning, and development. In K.A. Renninger, S. Hidi, & A. Krapp (Eds.), The Role of Interest in Learning and Development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 3–26.

Mödritscher, F., García-Barrios, V.M., and Maurer, H. (2005). The use of a dynamic background library within the scope of adaptive e-learning. Proceedings E-Learn 2005. Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 3045–3052.

Mödritscher, F., Gütl, C., García-Barrios, V.M., & Maurer, H. (2004). Why do standards in the field of e-learning not fully support learner-centred aspects of adaptivity? Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 2004. Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 2034–2039.

Mödritscher, F., & Sindler, A. (2005). Quizzes are not enough to reach high-level learning objectives. Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 2005. Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 3275–3278.

Mödritscher, F., Spiel, S., & García-Barrios, V.M. (2006). Assessment in E-Learning Environments: A Comparison of three Methods. In: Proceedings of SITE 2006, Chesapeake, VA: AACE. (to appear)

Park, O., & Lee, J. (2004). Adaptive Instructional Systems. In D.H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 651–684.

Phillips, M. (2005). Cognitive Style’s influence on Media Preference: Does it matter or do they know? Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 2005. Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 1023–1028.

Paulsen, T. (2005). Emotion, memory, and stories. In B. Hoffman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Educational Technology. http://coe.sdsu.edu/eet/articles/storyemotions/index.htm (2006-03-05).

Riding, R. (1991). Cognitive style analysis. Birmingham: Learning and Training Technology.

Sánchez J., & Flores, H. (2004). AudioMath: Blind children learning mathematics through audio. Proceedings of ICDVRAT 2004, Oxford, United Kingdom, 183–189.

Stash, N., Cristea, A., & De Bra, P. (2004). Authoring of learning styles in adaptive hypermedia: Problems and solutions. Proceedings of WWW 2004, 114–123.

Thorndike, E.L. (1913). Educational Psychology (Vol. 2). New York: Columbia University Press.

Tobias, S. (1987). Learner characteristics. In R.M. Gagné, (Ed.), Instructional Technology: Foundations. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Tobias, S. (1994). Interest, prior knowledge, and learning. Review of Educational Research, 64 (1), 37–54.

Tobias, S., & Ingber, T (1976). Achievement-treatment interactions in programmed instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 68, 43–47.

Ueno, M. (2004). Animated agent to maintain learner’s attention in e-learning. Proceedings of E-Learn 2004. Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 194-201.

Vassileva, J. (1996). A task-centered approach for user modeling in a hypermedia office documentation system. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 6 (2-3), 185–224.

Winn, W., & Snyder, D. (1996). Cognitive perspectives in psychology. In D.H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology. New York: Macmillan, 115–122.

About the Author

| Felix Mödritscher is researcher, software engineer, and project manager at the Institute for Information Systems and Computer Media (IICM) at the Graz University of Technology. Further, he is lecturer on the courses information design and knowledge management at the Graz University of Applied Sciences Degree Program in IT and IT-Marketing (CAMPUS 02). He has a M.Sc. (Dipl.-Ing.) in Computer Technics (Telematics). His research interests focus on pedagogical, didactical, and technological issues of e-learning as well as knowledge management. Felix Mödritscher Phone: +43 316 873 5622 Email: fmoedrit@iicm.edu |