| March 2010 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: Many factors influence successful use of instructional technology – ease of use, acceptance by faculty and students, reliability and technical support, and quality of instructional design, communication and feedback, and overall effectiveness. This study focuses on student experiences with e-learning and Learning Management Systems.

Learning from Group Interviews: Exploring Dimensions of Learning Management System Acceptance

Muneer Abbad

Saudi Arabia / Jordan

Abstract

This study aims to identify some of the main factors that affect students’ intentions to adopt e-learning systems. The paper reports the results of group interviews with students and tutors studying and teaching at the Arab Open University in Jordan. Content analysis was used to analyze qualitative data obtained from the interviews. The main categories used to analyze the data were derived from prior studies using the technology acceptance model (TAM) and the literature on IT systems’ acceptance in general and in the specific e-learning domain. The main categories that were used to analyze qualitative data were ease of use, perceived usefulness, subjective norms, prior Internet experience, system interactivity, self-efficacy and availability of technical support.

Introduction

The Internet and the web offer new opportunities to restructure the learning and knowledge transfer environment. For example, Rosenberg (2001: 80) suggested that, “Internet technologies have fundamentally altered the technological and economic landscapes so radically that it is now possible to make quantum leaps in the use of technology for learning”. Czerniak et al. (1999) stated that the new technologies in the twenty-first century have stimulated efforts towards shifting pedagogy from its conventional classroom-centered stronghold into a vibrant electronic web-based interactive learning environment. In addition, the advanced technology it uses offers distinct advantages to both educators and students (Banga and Downing, 2000). Many institutions of higher education now adopt web-based learning systems for their e-learning courses. However, there is a lack of empirical examination of factors underlying the student adoption of web-based learning systems (Ngai et al., 2007). Successful adoption requires a solid understanding of user acceptance processes and how to entice students to accept these technologies (Saadé and Bahli, 2005).

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) of Davis (1989) has set the basis for research in information and computer technology adoption and use (Gefen and Straub, 2000; Gefen, 2003; Stoel and Lee, 2003). TAM is an intention-based model that was developed specifically for explaining and predicting user acceptance of computer technology. Although the TAM initially focused on system usage in the workplace, researchers have employed the model to help understand website usage (Teo et al., 1999; Moon and Kim, 2001). Recently, technology acceptance has been applied to the domain of e-learning (Carswell and Venkatesh, 2002). The TAM posited the beliefs of perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) as the determinant factors for the intention to use IT (Davis, 1986). IT usage intentions, in turn, are assumed to directly influence actual use. The two variables (PU and PEOU) have thus been hypothesized to be fundamental factors of user acceptance of information technology.

Much research has addressed the antecedents of technology use (Mahmood et al., 2001), but the overwhelming majority of studies have focused on users in developed countries. Developing regions of the world have much to gain from the Internet and IT in general, but have received relatively little research attention (e.g. Hasan and Dista, 1998) even though culture may influence technology use (Veiga et al., 2001). Jordan is witnessing rapid developments in information technology. It has convenient telecommunication facilities among neighboring countries and it applies the latest technologies in Internet services. Jordan was chosen by the World Economic Forum (WEF) in 2003 to serve as a pilot country for the initiative and to serve as a benchmark for development in other countries in the region (WEF, 2003). In addition, The WEF is expected to launch a global education initiative based on the Jordanian model to be implemented in several countries in the region and beyond, including Egypt, India, and Pakistan. The Arab Open University (AOU) was the first Jordanian university to adopt e-learning on a widespread basis and plays a critical role in e-learning development nationally. It operates in partnership with the UK Open University (OU) and uses a Moodle-based e-learning management system to deliver courses and support to learners.

The Technology Acceptance Model

Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness

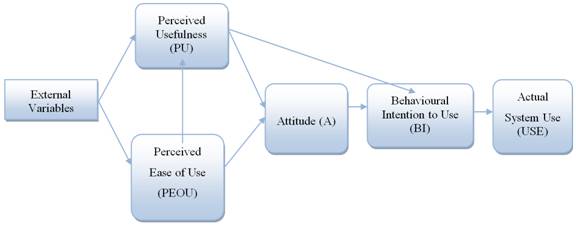

Davis (1989) stated that the goal of the TAM is to provide a basis for tracing the impact of external factors on internal beliefs, attitudes, and intention to use computers. The TAM model (see Figure 1) posits that two particular beliefs, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU), are of the primary relevance for computer acceptance behaviours.

Figure 1: Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

Perceived usefulness (PU) is defined as “the prospective probability that using a specific application system will increase his or her job performance within an organizational context” (Davis, 1986: 26). Perceived ease of use (PEOU) refers to “the degree to which the prospective user expects the target system to be free of effort” (Davis, 1986: 26). In the e-learning context, perceived usefulness refers to the extent that a student believes that use of the LMS will improve his or her performance.

However, perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness may not fully reflect users’ intentions to adopt a system, and researchers need to address how other factors affect usefulness, ease of use, and user acceptance (Davis, 1989). These factors are likely to vary with the technology, target users, and context (Moon and Kim, 2001). Selim (2003) used the TAM model to assess students’ acceptance of course websites as an effective learning tool. The results showed that course website usefulness and ease of use proved to be key determinants of the acceptance and usage of course websites.

Subjective Norm (SN)

Davis et al. (1989) believed that in some cases people might use a system to comply with the mandates of others rather than their own feelings and beliefs. Adler (1996) argued that social pressure could affect behaviour of individuals in varying degrees in different societies depending on the culture. In terms of technology acceptance, individuals from a collectivist culture may be predisposed to use computers because of the perceived social pressure from superiors and peers.

Empirical support for the relationship between social norms and behaviour can be found in many studies (e.g. Tornatsky and Klein, 1982; Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). Individuals can choose to perform a specific behaviour even if they do not feel positive towards the behaviour or its consequences. The choice depends on how important the individuals think that key referents believe that they should act in a certain way (e.g. Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975, Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). Recently, Lee (2006) found that the effects of subjective norms (SN) significantly influenced perceived usefulness. In the e-learning context, Kim et al. (2005) suggested that SN influences the learner’s satisfaction with and motivation for e-learning. In addition, the SN was a significant prediction of students’ satisfaction (Gunawardena and Zittle, 1997). Frith (2002) found that social factors enhanced students’ motivation and satisfaction.

Technology in e-learning does more than just supplement traditional communication. Gay and Lentini (1995) argued that e-learning is built through conversations between the instructor and students or among peers using chat rooms, electronic mail, and discussion groups. Although the TAM is useful in determining factors affecting technology acceptance and use, it is not capable of examining the effect of user communication patterns. In this study, subjective norm refers to a student’s perception of opinions or suggestions of the significant referents concerning his or her acceptance of an e-learning system (LMS) at AOU. This need not be an explicit statement or order from the instructors, friends, and/or family. The focus of the measurement was to examine how a student subjectively evaluated the thought of important referents in their decision process.

Internet Experience (IE)

Research studies suggest that prior experience is important in an individual’s acceptance of IT. Additionally, prior experience has been found to strongly influence intention to use and usage of a specific system through perceived ease of use (Agarwal and Prasad, 1999) and through perceived usefulness (Jiang et al., 2000). As O’Cass and Fenech (2003) point out, when Internet users have accumulated sufficient personal experience via their adoption of computer technology, it creates a belief in their ability to use the Internet for learning purposes. Kerka (1999) stated that, in (online) distance learning, learner success depends on technical skills in computer operation and Internet navigation, as well as the ability to cope with technical difficulty. Conrad (2002) found that students who had more experience in e-learning courses were less likely to feel anxious about e-learning. Similarly, Arbaugh and Duray (2002) found that students who had more experience in e-learning courses were more likely to be satisfied with e-learning systems.

System Interactivity (SI)

Previous research suggests that system characteristics can influence the intention to use and usage behaviour of the system. For example, Davis et al. (1989) proposed that system characteristics exhibit indirect effects on usage intentions or behaviours through their relationships with perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Davis (1993) showed that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use mediates the effects of system characteristics on usage behaviour. Bates (1991) noted that the main advances in distance education would come from technology that allowed increased learner interaction. Two types of interaction would be provided by a web-based learning system: instructor-to-student and student-to-student interactions. Palloff and Pratt (1999: 5) stated that “the key elements of learning processes are the interactions among students themselves, the interactions between faculty and students, and the collaboration in learning that results from these interactions”.

Tools are used to facilitate interaction include discussion forums, chat systems, e-mail, and more recently, social software and desktop conferencing systems. Interaction can be asynchronous or synchronous. In asynchronous discussions, there is no time and space constraint for students to engage in discussions on diverse topics with facilitators and peers. The availability of interactive applications such as discussion forums and e-mail facilitates the interactivity. In the opinion of some, the asynchronous learning environment is the preferable method for fostering in-depth student-rich interactions (Bonk et al., 1998). There is also a significant relationship between interactivity and learning effectiveness. Poon et al. (2004) found that students’ grades are highly correlated with students’ interactivity. Hence, system interactivity is expected to be one of the factors that may affect students’ adoption of e-learning systems.

Self-Efficacy (SE)

Self-efficacy is a belief in an individual’s capability to perform certain behaviours or it is one’s personal belief about his or her ability to perform certain tasks successfully (Bandura, 1986, 1997). With respect to Internet-related tasks, self-efficacy can be an important factor in considering whether or not a new process is adopted (O’Cass and Fenech, 2003). Davis et al. (1989) and Venkatesh and Davis (1996) suggested that self-efficacy is an antecedent of perceived ease of use and object usability. Compeau and Higgins (1995) also found that computer self-efficacy was a significant determinant of behavioural intention to use information technology. Dishaw et al. (2002: 1024) note that “self-efficacy constructs have been widely used in the educational literature to study academic performance”. Lu and Hsiao (2007) and Rao and Troshani (2007) used computer self-efficacy as a proxy for an individual’s internal control in the IT usage context. Venkatesh and Davis (1996) found computer self-efficacy acts as a determinant of perception of ease of use at all times. Agarwal et al. (2000) found that self-efficacy is an important determinant of perceived ease of use.

In the e-learning context, self-efficacy is interpreted as one’s self-confidence in his or her ability to perform certain learning tasks using an e-learning system. For example, students with a high sense of educational self-efficacy believe that they can study using an e-learning system while students with a low sense of educational self-efficacy may believe they cannot study using an e-learning system. A student who has a strong sense of his or her capability in dealing with an e-learning system has a more positive perception of ease of use and usefulness and he or she is more willing to accept and use the system. A student’s self-efficacy affects her/his actual behavioural decision or intention toward the educational process as well as their specific educational activities.

Technical Support (TS)

Ralph (1991) defined technical support as people assisting the users of computer hardware and software products, which can include hotlines, online support service, machine-readable support knowledge bases, faxes, automated telephone voice response systems, remote control software and other facilities. Technical support is an important factor in acceptance of technology for teaching (Sumner and Hostetler, 1999; Hofmann, 2002; Williams, 2002) and in user satisfaction (Mirani and King, 1994).

Technical support from the university is essential to achieve significant success in applying information technology in learning. In addition, technical support is especially important in the beginning stage of technology adoption. Hadley and Sheingold (1993) noted the importance of day-to-day help with problems of time, space, supervision, operation, and access that must be addressed to accomplish successful information technology adoption in schools by teachers through staff development and technical support. Venkatesh (2000) found facilitating conditions and external control served as anchors that users employ in forming perceived ease of use about information technology. In contrast, some e-learning projects that were not successful in achieving their goals did not have access to technical advice and support (Alexander and Mckenzie, 1998; Soong et al., 2001). If technical support is lacking, e-learning will not succeed (Selim, 2003). Recently, Ngai et al. (2007) extended the TAM to include technical support as a precursor in user acceptance of WebCT.

Methodology

Group interviews were conducted at the Arab Open University (AOU) in Jordan. The AOU has two main branches in the biggest cities in Jordan, namely Amman (the capital) and Irbid. Participants in the study consisted of undergraduate students who were taking the last lecture of the first basic computer literacy course. Three group interviews were conducted in the Irbid branch and three group interviews were conducted in the Amman branch. All the sessions were video-recorded for later analysis. Nine to twelve students per group and five tutors participated in the group interviews. Two of the tutors were working full-time and three of them were working part-time. All the tutors have more than four years experience in teaching using e-learning systems (First-class and LMS). Table 1 shows variables with regard to gender and school of students who participated in the group interviews. Table 2 shows the distribution of students’ age.

Distribution of Students’ Gender and School

Student | Number of participants | Male | Female | School |

1 | 10 | 6 | 4 | IT |

2 | 9 | 5 | 4 | IT |

3 | 11 | 6 | 5 | IT |

4 | 10 | 5 | 5 | Education |

5 | 12 | 5 | 7 | Education |

Total | 52 | 27 | 25 |

Distribution of Students’ Age

Age | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | Total |

18-22 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 13 |

23-27 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 15 |

28-32 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

33-37 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

Over 37 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, 27 of the students were male and 25 were female. Three groups from the IT school (TU170 course) and two groups from the education school (GR100 course) participated in the interviews. In addition, the sample covers different ages: 13 of the participants were 18-22 years old, 15 of the students were 23-27 years old, and the remainder (24 students) were over 27 years old.

The group interviews were semi-structured. However, there was an openness to change of sequence and forms of questions in order to follow up the answers given. A pilot test of the interview design was conducted with 10 students at AOU in Jordan. The time required for each session was between 60 to 90 minutes.

In this research, the categorization approach was used to analyze group interviews. This was compatible with the research goals and concerned with the main factors that may affect students’ adoption of e-learning systems with an openness to add, delete, or modify the main categories. The interviews were categorized independently by two coders and their coding was combined. Several meetings were held with the coders to confirm coding and resolve disagreements.

All group interviews in this phase were converted into text by transcribing the recorded interviews and auditing the transcripts against the recordings prior to analysis. All the sessions were conducted in the Arabic language.

Quantitative and qualitative coding methods were used to identify the principal factors that affect students’ adoption of the LMS. Categories were identified to classify the data within different categories. Categories were based on the factors collected from the literature and TAM model, namely: ease of use, usefulness, subjective norms, Internet experience, system interactivity, self-efficacy, and technical support.

Content analysis is a method that is used regularly to analyze qualitative data obtained from group interviews (Morgan, 1996; Merriam, 1998). Based on the indicators used in the literature, the main subcategories were given to the coders to explain the categories in much more detail. Accordingly, the coders identified the subcategories by grouping similar themes associated with the main categories.

Findings

In this section, the analyses of students’ responses about the main factors that may affect their intention to use the LMS are described. Under each category, the coders identified subcategories by grouping similar themes associated with the main categories. A summary of the main categories and subcategories are illustrated in Table 3.

The Main Categories and Subcategories of Factors

Main Categories | Subcategories |

Ease of Use | Easy; clear |

Usefulness | Useful; speed; performance |

Subjective Norms | Colleagues’ effect; tutor’s effect |

System Interactivity | Interactivity between students and tutor; interactivity among students |

Self-Efficac y | Confidence; comfort |

Internet Experience | Frequency of use; familiarity of use |

Technical Support | Training; university support. |

Additionally, the numbers of students who agreed or disagreed with main categories as factors that may affect their adoption of the LMS are summarized in Table 4.

The Number of Students who Identified the Categories as being Important

Main Categories | Agreed | Disagreed |

Useful | 37 | 0 |

Ease of Use | 37 | 5 |

Internet Experience | 24 | 3 |

Technical Support | 22 | 4 |

System Interactivity | 21 | 8 |

Self-Efficacy | 18 | 8 |

Subjective Norms | 15 | 10 |

Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)

Most of the students stated that the LMS was easy to use. The total number of students in all groups who accepted that ease of use of LMS is one of the factors that affects their intention to use LMS was 37 of 52 and the number of students who disagreed was 5 (see Table 4), and some students had did not give any comment in relation to this factor. Therefore, the results in general accepted that ease of use influenced students’ intention to use LMS, although there were differences between the groups This varied from 9 of the 10 students of the first group agreeing (none disagreed) to 6 of the 12 students of the fifth group who agreed and 2 who disagreed. Additionally, the coders identified two subcategories of this factor according to the indicators used in the literature, namely ‘easy’ and ‘clear’. of the system In the literature, easy and clear are the main important indicators used to measure the perceived ease of use construct (Davis, 1986; Venkatesh and Davis, 2000).

For instance, one student said that:

“I find the LMS is very easy to practice on, and I find out what I want from it”

Another student reported that:

“Because the LMS is clear, it motivates me to use the system and helped me a lot to learn”

Some students gave some indications about the relationship between ease of use and usefulness. As an example, one of the students said that:

“I am very happy with it. It is easy to take the information by practice, where things were not understood in lectures and that helped me to learn”

However some students believe they have to use a system even if it is difficult. For instance, one of the students said:

“Whatever the system is easy or not I will use it to submit my assignment”.

Perceived Usefulness (PU)

In the e-learning context, perceived usefulness refers to the extent that a student believes that use of the LMS will improve his or her performance. Table 4 shows the results of the students’ responses to this factor. The results in general support the idea that perceived usefulness influenced students’ intention to use the LMS. This varied from 8 of the 11 students of the third group (none disagreed) to 7 of the 12 students of the fifth group accepting and none disagreeing.

The coders classified the words and themes that students used to express their feelings and beliefs about this factor into three main subcategories (see Table 3), namely useful, speed, and performance. Most of the studies that have used the TAM model as a framework used these subcategories as main indicators to measure the perceived usefulness construct (Davis, 1986; Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). Students in this study referred to these indicators. For instance, one of the students explained how she got the motivation to study through LMS when she said:

“LMS is useful for me to see the announcements about each course. Also, I used the system to download the PowerPoint presentations”.

Many students interviewed in this study noted the usefulness of LMS as the most important factor affecting students’ intention to use LMS. Since the LMS helped them to accomplish their tasks quickly, practice for the exam and complete assignments, it had a positive influence on their use of LMS, as noted in the following comment:

“I can finish my tasks quickly through LMS, I visited the website regularly to complete assignments, and it also gave me practice for the actual exams and quizzes”

Another student stated:

“LMS is very easy and useful for me. I usually use LMS to learn and solve assignments”

External Factors

Without incorporating external factors, the TAM provides only very general information on users’ opinions about the system, but does not yield “specific information that can better guides the system development” (Mathieson, 1991: 173). Several previous studies have shown that there are various external factors that indirectly influence the acceptance of technology through perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (Davis et al., 1989; Szajna, 1996).

Students were asked whether they agreed or disagreed about some factors that make the system easy to use and useful for them. Table 4 shows that the main factors that may affect students’ adoption of LMS through perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness were Internet experience, technical support, system interactivity, self-efficacy, and subjective norm. Additionally, Table 4 depicts how many of the 52 students agreed or disagreed with the five factors. This varied: 24 of 52 students of all groups agreed, and 3 disagreed that Internet experience makes LMS easy to use and useful for them; to 15 of 52 students agreed and 10 students disagreed that subjective norms make LMS easy to use and useful for them.

5

Selected Representative Positive and Negative Comments about each Factor

Factor | Aspect | Comment |

SN | Representative positive comment | I am very impressed; most colleagues used the system and motivated me to use LMS. They taught me how to use it. |

Representative negative comment | LMS is a great system but I feel that some tutors don’t understand or know how it works. | |

IE | Representative positive comment | LMS is very useful. I am using my Internet experience to find what I want. |

Representative negative comment | I have access to the system in the university and I think it is a waste of time. | |

SE | Representative positive comment | LMS is easy and useful for me and I feel comfortable with it. |

Representative negative comment | It seems good but it is too hard to use. | |

SI | Representative positive comment | I found LMS very useful because I got answers from other students and my tutor to my questions on the discussion forum |

Representative negative comment | The tutors didn’t reply even when I tried to send questions to them a few times. | |

TS | Representative positive comment | Staff is accessible at any time and they resolve queries and questions. |

Representative negative comment | There is not as much support and facilities from the university as I expected. |

Under each main response category, the coders identified subcategories by grouping similar themes associated with the main category. Table 3 illustrated the main categories and subcategories for each factor. Two main themes are specified for system interactivity, namely the interactivity between students and tutors and the interactivity among students. Two main themes are specified for self-efficacy, namely confidence and comfort. For Internet experience, the main themes are the colleagues’ effect and the tutor’s effect. Finally, for technical support, the main themes are training and university support. Table 5 provides selective representative positive and negative comments from which the coders identified the main subcategories. Some examples are discussed in the following subsections.

System Interactivity (SI)

When students believe that the system provides for effective student-student and student-tutor interactions, they will be more likely to use the LMS. As one student stated:

“I found LMS very useful because I got answers from other students and my tutor to my questions on the discussion forum”

On the other hand, other students disagreed , they found the LMS was not useful because they did not get answers to their questions from either students or tutor. The students had to wait a long time to get answers, as one student noted as follows:

“The students and tutor didn’t reply even when I tried to send questions to them a few times”.

In general, the students commented that interactions with other students and their tutor in the LMS were beneficial for them.

Self-Efficacy (SE)

Self-efficacy is defined as “Judgment of one’s capability to use what has been done in the past, but rather with judgment of what can be done in the future” (Compeau and Higgins, 1995: 192). If users are struggling, they may actually believe that the system is not easy to use and that the benefits of using the system in terms of performance are outweighed by the effort of using it (Pituch and Lee, 2006).

Two subcategories were identified to the self-efficacy factor, confidence and comfort. The system will be useful and easy to use when students have the confidence in their ability to perform learning tasks using the LMS. Some students commented on the confidence of using LMS:

“LMS is very useful because I can print the lecture notes, I can take the pre-quiz at home, and I can check announcements”.

Subjective Norm (SN)

Subjective norm is defined as an “individual’s perception that most people who are important to him/her think s/he should or should not perform the behavior in question” (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975:302).Tutors can play a supporting role by motivating students to use the system and teach them how to use it. A student commented on this role:

“Our tutor motivates us to do the required assignments and I like working on LMS”.

Another student commented on the motivation from her colleagues:

“I am very impressed; most of my colleagues used the system and motivated me to use LMS. They taught me how to use it”.

Other students found the system good and useful but the tutors did not understand and know how it worked. As one student said:

“LMS is a great system but I feel that some tutors don’t understand and know how it works”.

Prior Internet experience influences students’ perceptions of ease of use and usefulness of the LMS. The students can use their experience to find what they want from the system. Frequency and familiarity of use of the Internet are the main themes that describe this factor. A student commented on using his Internet experience to find what he wanted:

“I have good Internet experience, I found LMS very easy to find what I want”.

Another one said:

“I am not familiar with the Internet but I frequently use the system to learn and submit assignments”.

Technical support is defined as people assisting the users of computer hardware and software products, which can include hotlines, online support service, machine-readable support knowledge bases, faxes, automated telephone voice response systems, remote control software and other facilities (Ralph, 1991).

Training and university support were the main themes of this factor. Most students focused on the training because they felt that training was very import in the earlier stage. The following are some students’ comments on the usefulness of training and university support:

“Staff are accessible at any time and they resolve queries and questions”.

“I use the university system to download material and submitting assignments because the system of the university is quicker than the system I have at home”.

“If I need technical support in the evening, I have to go to the university to ask. There are no enquires by e-mail”.

“I took a training course at AOU and that helped me a lot to understand and use LMS”.

“I didn’t take the training course; this course is just available in one branch Amman, because of that I have to ask before using the system”.

“LMS could be easy and useful if all the students take training”.

Tutor Interviews

The factor identified above was discussed with tutors who were working at AOU. The discussion started with the same general question that was asked of students:

“What are the main factors that may affect students’ adoption of e-learning systems?”

Then, discussion moved to specific questions and issues about each factor. For instance, one of the part-time tutors said that:

“Part-time tutors usually access the system less than the full-time tutors because the part-time tutors have a full teaching load in their universities and there is no time to check and collaborate with students. While full-time tutors usually work frequently on the system and they are active with their students”.

Thus, this tutor focused on the system interactivity factor and he did not have time to collaborate with his students as full-time tutor. On the same factor, another tutor said:

“There are no questions from the students because most of them are working and they don’t have time to access LMS”.

Discussion and Conclusion

The results showed that five external factors, namely subjective norms, Internet experience, system interactivity, self-efficacy, and technical support, could explain the students’ intention to use e-learning systems, in addition to the main constructs of the TAM model (perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use).

The findings showed that self-efficacy is an important determinant of students’ adoption of an e-learning system. This is consistent with that results reported by Venkatesh and Davis (1996). A student’s Internet experience does influence perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. This finding is consistent with those of Igbaria et al. (1995) that the level of computing experience had a significant direct influence on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. This study also showed that subjective norm had an effect on students’ intentions and this result was consistent with the extended model of the TAM (TAM2) (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). Students who had stronger subjective norms have greater motivation to use the e-learning system.

System interactivity is the perception of students of the system’s ability to provide interactive communications between instructor and students and interactive communication among students. From the results, technical support (such as training and support) was found to have an effect on intention to use. This result was consistent with Ngai et al. (2007) findings. This showed the importance of user support and training in influencing the perceptions of students.

References

Adler, R. (1996) Older adults and computers: Report of a national survey [online] available from http://www.seniornet.org/php/default.php?PageID=5476&Version=o&Font=oFrissen. [15 December 2005].

Agarwal, R. and Prasad, J. (1999) ‘Are individual differences germane to the acceptance of new information technologies?’ Decision Sciences 30, (2) 361-91.

Aggarwal, A. (2000) Web-based learning and teaching technologies: Opportunities and challenges. London: Idea Group Pub.

Alexander, S. and McKenzie, J. (1998) An Evaluation of Information Technology Projects in University Learning. Department of Employment, Education and Training and Youth Affairs, Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Services.

Arbaugh, J.B. and Duray, R. (2002) ‘Technological and structural characteristics, student learning and satisfaction with Web-based courses: An exploratory study of two online MBA programs.’ Management and Learning 33, (3) 331–347.

Bandura, A. (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs: NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997) ‘Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change.’ Psychological Review 82, (2) 191-215.

Banga, S. and Downing, K. J. (2000) Moving towards global education in the twenty-first century. Abramson, M., Towards the Global University: Reading Excellence in the Third Millennium, University of Central Lancashire, Preston.

Bates, A. W. (1991) ‘Third generation distance education: The challenge of new technology.’ Research in Distance Education 3, (2) 10-16.

Bonk, C. J. and Cunningham, D. J. (1998) Searching for learner-centered, constructivist, and socio-cultural components of collaborative educational learning tools. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associated, Publishers.

Carswell, A. D. and Venkatesh, V. (2002) ‘Learner outcomes in an asynchronous distance educational environment.’ International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 56, (5) 475-494.

Compeau, D.R. and Higgins, C.A. (1995) ‘Computer self-efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test.’ Management Information Systems Quarterly 19, (2) 189-211.

Conrad, D.L. (2002) ‘Conrad, Engagement, excitement, anxiety, and fear: Learners' experiences of starting an online course.’ American Journal of Distance Education 16, (4) 205–226.

Czerniak, C. Lumpe, A., Haney, J. and Beck, J. (1999) ‘Teachers’ beliefs about using educational technology in the science classroom.’ International Journal of Educational Technology [online] 1, (2), available from http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ijet/v1n2/czerniak/index.html [10 July 2007].

Davis, F. D. (1986) A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results. (Doctoral dissertation, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P. and Warshaw, P. R. (1992) ‘Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace.’ Journal of Applied social Psychology 22, (14) 1111-1122.

Davis, F.D. (1989) ‘Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology.’ MIS Quarterly 13, (3) 319-340.

Davis, F.D. (1993) ‘User acceptance of information technology: system characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts.’ International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 38, (1) 475-87.

Dishaw, M. T., Strong, D. M. and Bandy, D. B. (2002) ‘Extending task-technology fit model with self-efficacy constructs.’ Human-Computer Interaction Studies in MIS, (1) 1021-1026.

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975) Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Frith, K. H. (2002) Effect of conversation on nursing student outcomes in a Web-based course on cardiac rhythm interpretation. Doctoral dissertation, Georgia State University, Atlanta.

Gay, G. and Lentini, M. (1995) ‘Use of communication resources in a networked collaborative design Environment.’ Journal of Computer Mediated Communication [online] 1, (1) available from http://cwis.usc.edu/dept/ annenberg/vol1/issuel/ contents.html [5 July 2007].

Gefen, D. (2003) ‘TAM or just plain habit: A look at experienced online shoppers.’ Journal of End User Computing15, (3) 1-13.

Gefen, D. and Straub, D. (2000) ‘The relative importance of perceived ease of use in IS adoption: A study of e-commerce adoption.’ Journal of the Association for Information Systems 1, (8) 1-30.

Gunawardena C.N. and Zittle, F.J. (1997) ‘Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer-mediated conferencing environment.’ American Journal of Distance Education 11, (3) 8–26.

Hadley, M. and Sheingold, K. (1993) ‘Commonalties and distinctive patterns in teachers’ integration of computers.’ American Journal of Education 101, (3) 261-315.

Hasan, H. and Ditsa, G. (1998) ‘The Impact of Culture on the Adoption of IT: An Interpretive Study.’ Journal of Global Information Management 7, (1) 5-15.

Hofmann, D.W. (2002) ‘Internet-based distance learning in higher education.’ Tech Directions 62, (1) 28–32.

Igbaria, M., Gamers, T. and Davis, G.B. (1995) ‘Testing the determinants of micro-computer usage via a structural equation model.’ Journal of Management Information Systems 11, (4) 87-114.

Jiang, J.J., Hsu, M.K., Klein, G. and Lin, B. (2000) ‘E-commerce user behavior model: an empirical study.’ Human Systems Management19, (4) 265-276.

Kerka, S. (1999) Distance learning, the Internet, and the World Wide Web. ERIC Digest, ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 395214.

Kim, K., Liu, S. and Bonk, C.J. (2005) ‘Online MBA students' perceptions of online learning: Benefits, challenges, and suggestions.’ The Internet and Higher Education 8, (4) 335-344.

Lee, Y.C. (2006) ‘An empirical investigation into factors influencing the adoption of an e-learning system.’ Online Information Review 30, (5) 517-541.

Lu, H. and Hsiao, k. (2007) ‘Understanding intention to continuously share information on weblogs.’ Internet Research17, (4) 43-66.

Mahmood, M. A., Hall, L. and Swanberg, D. L. (2001) ‘Factors Affecting Information Technology Usage: A Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Literature.’ Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce 11, (2) 107-130.

Mathieson, K. (1991) ‘Predicting user intentions: comparing the Technology Acceptance Model with the theory of planned behavior.’ Information Systems Research 2, (3) 173-191.

Merriam, S. B. (1998) Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Mirani R. and King, W.R. (1994) ‘Impacts of end-user and information center characteristics on end-user computing support.’ Journal of Management Information Systems 11, (1) 141–166.

Moon, J. and Kim, Y. (2001) ‘Extending the TAM for a World Wide Web Context.’ Information and Management 38, (4) 217-231.

Morgan, D. (1996) ‘Focus Groups.’ Annual Reviews Inc 22, 129-152.

Ngai, E.W.T., Poon, J.K.L. and Chan, Y.H.C. (2007) ‘Empirical examination of the adoption of WebCT using TAM.’ Computers and Education 48, (2) 250-267.

O’cass A. and Fenech, T. (2003) ‘Web retailing adoption: exploring the nature of internet users Web retailing behavior.’ Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 10, (1) 81–94.

Palloff R.M. and Pratt, K. (1999) Building learning communities in cyberspace: Effective strategies for the online classroom. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, CA.

Pituch, K. A. and Lee, Y. (2006) ‘The influence of system characteristics on e-learning use.’ Computers and Education 47, (2) 222-244.

Poon, W., Low, K. L. and Yong, D. G. (2004) ‘A study of Web-based learning (WBL) environment in Malaysia.’ The International Journal of Educational Management 18, (6) 374-385.

Ralph, W. (1991) The art f computer technical support. California: Peachipt Press.

Rao, S. and Troshani, I. (2007) ‘A conceptual framework and propositions for the acceptance of mobile services.’ Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2, (2) 61-73.

Rosenberg, M.J. (2001) E-learning: Strategies for delivering knowledge in the digital age. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Saadé, R. and Bahli, B (2005) ‘The impact of cognitive absorption on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use in on-line learning: an extension of technology acceptance model.’ Information and Management 42, (2) 317-327.

Selim, H.M. (2003) ‘An empirical investigation of student acceptance of a course websites.’ Computers and Education 40, (4) 343-360.

Soong, M.H.B., Chan H.C., Chua, B.C. and Loh, K.F. (2001) ‘Critical success factors for on-line course resources.’ Computers and Education 36, (2) 101-120.

Stoel, L. and Lee, K. H. (2003) ‘Modeling the effect of experience on the student acceptance of web-based courseware.’ Internet research: Electronic Network Applications and Policy 13, (5) 364-374.

Sumner M. and Hostetler, D. (1999) ‘ Factors influence the adoption of technology in teaching.’ Journal of Computer Information Systems 40, (1) 81–87.

Szajna, B. (1996) ‘Empirical evaluation of the revised technology acceptance model.’ Management Science 42, (1) 85–92.

Teo, T., Lim, V. and Lai, R. (1999) ‘Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in Internet usage.’ Omega International Journal of Management 27, (1) 25-37.

Tornatsky, L.G. and Klein, K.J. (1982) ‘Innovation characteristics and innovation adoption-implementation: a meta-analysis of findings.’ IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management,

(1) 28-45.

Veiga, J. F., Floyd, S. and Dechant, K. (2001) ‘Towards modeling the effects of national culture on IT implementation and acceptance.’ Journal of Information Technology 16, (1) 145-158.

Venkatesh, V. (2000) ‘Determinants of perceived ease of use: integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model.’ Information Systems Research 11, (4)

342-365.

Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F. (2000) ‘A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies.’ Management Science 46, (2) 186-204.

Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F.D. (1996) ‘A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: development and test.’ Decision Sciences 27, (3) 451-481.

WEF (2003) World Economic Forum: Report 2003. [online] Available from http://www.weforum.org

[21 October 2005].

Williams, P. (2002) ‘The Learning Web: the development, implementation, and evaluation of Internet-based undergraduate materials for the teaching of key skills.’ Active Learning in Higher Education 3, (1) 40-53.

About the Author

Muneer Abbad is from Effat University in Saudi Arabia.