| November 2010 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: This skillfully crafted research enables us to sort out the factors related to self-efficacy that are significant for low and high proficiency students to learn English as a foreign language.

The Influence of Self-Efficacy and Proficiency

on EFL Learners’ Writing

Massoud Rahimpour and Roghayyeh Nariman-Jahan

Australia and Iran

Abstract

The impetus of the present study was to investigate the impact of self-efficacy and proficiency on EFL learners’ written task performance regarding concept load, fluency, complexity and accuracy. One hundred and forty four low-proficiency and high-proficiency learners of English as a foreign language, between ages 18-25, were chosen. Each participant was requested to execute three tasks: a narrative task, a personal task, and decision-making task and fill out the self-efficacy questionnaire. The participants’ performances were then analyzed utilizing the Pearson correlation. The results demonstrated that there was a significant relationship between self-efficacy and narrative and personal tasks in terms of concept load but not in terms of fluency, complexity, and accuracy in high proficiency participants. Also, there was no relationship between self-efficacy and decision-making tasks in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy in both low and high proficiency participants.

Keywords: self-efficacy, proficiency, task type, concept load, fluency, complexity, accuracy, writing performance

Introduction

Self-efficacy is a cognitive construct that represents individuals’ beliefs about their ability to act and successfully produce outcomes at a given level (Bandura, 1977). Self- efficacy theory provides explicit guidelines on how to enable people to exercise some influence over how they live their lives. A theory that can be readily used to enhance human efficacy has much greater social utility than theories that provides correlates of perceived control but have little to say about how to foster desired changes.

As maintained by Bandura (1997) people make casual contributions to their own psychological functioning through mechanisms of personal agency. Among the mechanisms of agency, none is more central or persuasive than beliefs of personal efficacy. If people believe they have no power to produce results, they will not attempt to make things to happen. Unless people believe they can produce desired effects by their actions, they have little incentive to act. Efficacy belief, therefore, is a major basis of action. People guide their lives by their beliefs of personal efficacy. Thus, perceived self- efficacy refers to “beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (Bandura: 2-3).

Self-efficacy and Social Cognitive Theory

Bandura’s (1997) social cognitive theory is a theory of human functioning that subscribes to the notion that humans can regulate their behavior. Individuals possess self- beliefs that enable them to exercise control over their thought, feelings, and actions.

Social cognitive theory stresses the influential role of self- efficacy beliefs on human behaviors. Beliefs of personal efficacy are not dependent on one’s abilities but, instead, on what that person believes might be accomplished with his or her personal skill set. Such beliefs influence an individual’s pursued course of action, effort expended in given endeavors, persistence in the conformation of obstacles, and resilience to adversity. Self- efficacious individuals will therefore approach challenges with the intention and anticipation of mastery, intensifying their effort and persistence accordingly. These individuals rapidly recover their lowered sense of efficacy after enduring failure or difficulty, and attribute failure to insufficient effort or deficient knowledge. According to Bandura, “people’s beliefs of personal efficacy affect almost everything they do; how they think; motivate themselves, feel and have” (Bandura: 19).

Perceived self- efficacy occupies a pivotal role in social cognitive theory because it acts upon the other classes of determinants. Through choice of activities and the motivational level, beliefs of personal efficacy make an important contribution to the acquisition of the knowledge structures on which skills are founded. Beliefs of personal efficacy also regulate motivation by shaping aspirations and the outcomes expected for one’s efforts (Bandura, 1997). In short, perceived self- efficacy is concerned not with the number of skills you have, but with what you believe you can do with what you have under variety of circumstances.

Self-efficacy and Achievement

Perceived self-efficacy, or students’ personal beliefs about their capabilities to learn or perform behaviors at designated levels, plays an important role in their motivation and learning (Schunk, 2003). As Zimmerman (1997) said students’ perceived self- efficacy influenced their skills acquisition both directly and indirectly by highlighting their persistence. The direct effect indicates that perceived self- efficacy influences student’s learning through cognitive as well as motivational mechanisms. Considerable support has also been found regarding the effects of perceived self- efficacy on persistence. The overall findings of cross- sectional, longitudinal, and experimental studies are quite consistent in showing that beliefs in personal efficacy enhance effort and persistence in academic activities. Because perceived self- efficacy fosters engagement in learning activities that promote the development of educational competencies, such beliefs affect level of achievement as well as motivation. Efficacy beliefs have been shown to affect all three forms of academic performance (i.e. basic cognitive skills, performance in academic course work, and standardized achievement tests).

According to Bandura (1997) people’s beliefs in their efficacy have diverse effects. Such beliefs influence the courses of action people choose to pursue, how much effort they put forth in given endeavors, how long they persevere in the face of obstacles and failures, their resilience to adversity, whether their thoughts are self- hindering or self- aiding, how much stress and depression they experience in coping with taxing environmental demands, and the level of accomplishments they realize.

Furthermore, research findings demonstrate that more generalized self- efficacy perceptions are also good predictors of more generalized performances such as obtained grades, choice of academic majors, and intention to enroll in math- related courses speak to the practical utility both of self- efficacy and of expectancy beliefs in general (Pajares, 1996).

Self-efficacy and Writing

Mills, Pajares, and Herron (2007) pointed out that students’ self- efficacy beliefs powerfully affect their academic performance in various ways. Students with a strong sense of academic self- efficacy willingly undertake challenging tasks, expend greater effort, show increased persistence in the presence of obstacles, demonstrate lower anxiety levels, display their flexibility in the use of learning strategies, demonstrate accurate self- evaluation of their performance, and greater linguistic interest in scholastic matters, and self- regulate better than other students. As a consequence, they attain higher intellectual achievement. Conversely, students with low self- efficacy prefer to complete only uncomplicated academic tasks to which they apply minimal effort and limited persistence or they might choose entirely to avoid the completion of an academic assignment. For these reasons, self- efficacy beliefs are often said to be better predictors of academic success than are actual abilities (Bandura, 1997). In the case of writing the researchers demonstrated that self-efficacy plays a primary role in predicting student writing performance.

Pajares and Valiante (2001) investigated the influence of writing self-efficacy, writing apprehension, perceived usefulness of writing, and writing aptitude on the essay-writing performance of 218 fifth grade students. They found that self-efficacy beliefs made an independent contribution to the prediction of performance despite the expected powerful effect of writing aptitude.

Hidi, Berndorff, and Ainley (2002) examined the relation between students’ general interest in writing and their genre-specific liking and self-efficacy in writing. The results showed that children’s genre-specific liking and self-efficacy in writing are closely associated and that both of these factors are also associated with their general interest in writing.

Andrade, Wang, Du, and Akawi (2009) investigated the relation between long- and short-term rubric use (including self-assessment), gender, and self-efficacy for writing by elementary and middle school students (N = 268). They measured long-term rubric use with a questionnaire. They manipulated short-term rubric use by a treatment that involved reviewing a model and using a rubric to self-assess drafts. The authors collected self-efficacy ratings three Verdana. Results revealed that girls’ self-efficacy was higher than boys’ self-efficacy before they began writing. The authors found interactions between gender and rubric use: Average self-efficacy ratings increased as students wrote, regardless of condition, but the increase in the self-efficacy of girls in the treatment group was larger than that for girls in the comparison group, and long-term rubric use associated only with the self-efficacy of girls.

However, above studies and others examined the relationship between self-efficacy writing and writing. There is no research on relationship between general self-efficacy and writing. Also, there is no research on determining whether a different task type makes a difference or not. Moreover, whereas several studies have considered how the effect of self-efficacy varies according to the different factors imposed by the task or learner such as interest or aptitude, there has been almost no consideration of the interaction between self-efficacy and proficiency. Indeed, these studies have investigated learners with a very limited range of proficiency. They have examined mainly fifth grade students (e.g. Pajares and Valiante, 2001), junior intermediate learners (e.g. Hidi, 2002), elementary and middle school learners (e.g. Andrade, Wang, Du, and Akawi, 2009). Thus, to fill gap in the literature the main purpose of the present study was to investigate the relationship between general self-efficacy and task type in high and low proficiency learners.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

To achieve the purpose of the study, the following research questions and hypotheses were formulated:

1. What is the effect of self- efficacy on narrative tasks in low and high proficiency learners in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy?

2. What is the effect of self- efficacy on personal tasks in low and high proficiency learners in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy?

3. What is the effect of self- efficacy on decision-making tasks in low and high proficiency learners in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy?

Concerning the above- mentioned main research questions, the following hypotheses have been produced:

1. There is a significant relationship between self-efficacy and narrative tasks in low and high proficiency learners in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy?

2. There is a significant relationship between self-efficacy and personal tasks in low and high proficiency learners in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy?

3. There is a significant relationship between self-efficacy and decision-making tasks in low and high proficiency learners in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy?

Method

Participants

144 participants were chosen for this study on the understanding that they would be taking part in two tasks: 1) three tasks of writing and 2) a questionnaire. They were Iranian learners of English in Tabriz University. They formed two proficiency groups: 81 higher proficiency students and 87 lower proficiency students. They were all between 18 and 25 years old, and all were both females and males. At the time of data collection, most of them had been learning English as a foreign language in Iranian schools for 6 years, first in Junior school and then in high school. They had little opportunity to use English for communicative purposes outside the classroom. Although all the students, for pedagogical and practical reasons, were required to do all the tasks, several students were excluded from analysis in advance because they were absent in some of tasks.

The classes had begun 4 weeks before data- gathering was started. It was intended that this pre-research period would allow the classes to become established and would lead to more stable populations. All data were collected during normally scheduled class Verdana.

Materials

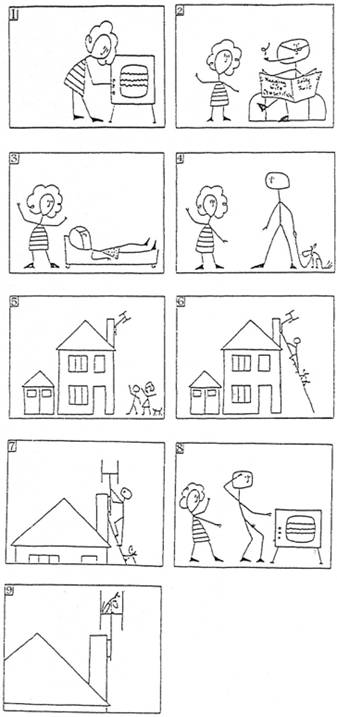

All tasks were carried out by participants in dyads. The three tasks (See Appendix A) used were a narrative based on pictures, a personal information exchange, and a decision- making task from Foster and Skehan (1996).

The General Perceived Self- Efficacy scale (Schwarzer and Jerusalem, 2000) was used to assess the participant’s self- efficacy (See Appendix B). Self- efficacy is commonly understood as being very specific; that is, one can have more or less firm self- beliefs in different domains or particular situations of functioning. But some researchers have also conceptualized a generalized sense of self- efficacy (Schwarzer and Jerusalem, 2000). The general self- efficacy scale aims at a broad and stable sense of personal competence to deal efficiently with a variety of stressful situations. The German version of this scale was originally developed by Jersalem and Schwarzer in 1981, first as a 20- item version and later as a reduced 10- item version. It has been in numerous research projects, where it typically yielded internal consistencies between alpha= 0.75 and 0.90. The scale is not only parsimonious and reliable, it has also proven valid in terms of convergent and discriminant validity. By confirmatory factor analyses it has found that the scale was unidimensional in all subsamples. The scale has 10 items with 4 point scale, ranging from A to D (A=not at all true), (B=barely true), (C=moderately true), and (D= exactly true).

Data collection procedures

After the participants and the materials were chosen, the procedure commenced. Each participant performed three tasks and filled out a questionnaire. Each class was visited on three occasions at weekly intervals and on each visit was one of the three tasks to do.

To find out the effect of self- efficacy on the participant’s performance, the participants were required to fill out the General Perceived Self- Efficacy questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of ten- item. The respondents were asked to rate how confident they are that they can do each of the 10 activities or tasks at present. Each item was rated by selecting a number on 4- point scale. Where 1 equals “not at all true” and 4 equals “exactly true”. A total score was calculated by summing the scores for each of the 10 items, yielding a maximum possible score of 40. Higher scores reflect stronger self- efficacy beliefs.

Measures

Measures of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy were developed to evaluate the quality of the participants’ written production.

The word types per square root of two Verdana the words was used as a measure of concept load (Ellis and Barkuizen, 2005), the number of words per T- unit was used as a measure of fluency (Ishikawa, 2006; Kuiken and Vedder, 2007), the ratio of clauses to T- units was used as a measure of complexity(Mehnert, 1998; Yuan and Ellis, 2003; Ellis and Yuan, 2004; Arnold, 2008; Wiggleworth and Storch, 2009), and the number of error- free T- units per t-units was used as a measure of accuracy Rahimpour (1997, 2008), Errasti (2003), Larsen- Freeman (2006), and Arnold (2008). These measures were used for analysis because these indices have been determined to be best measures of second language development in writing (Larsen- Freeman, 2006).

Results

In this section, the results were explained in two sections: 1) low proficiency learners and 2) high proficiency learners.

Self-efficacy: Low Proficiency Learners (Language Performances)

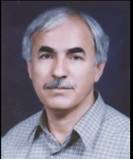

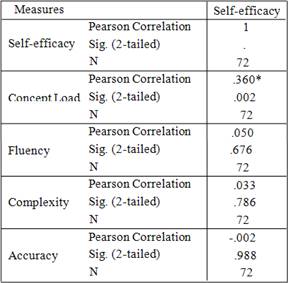

Table 1 provides a summary of the correlations for language performance of low proficiency participants in narrative tasks.

Table 1

Correlation between Self-efficacy and Language performance

in Narrative Tasks

As can be seen, the significance of Pearson correlation for concept load equals to 0.491, for fluency equals to 0.883, for complexity equals to 0.393, and for accuracy equals to 0.487 in low proficiency participants. According to Table 4.51, the research hypothesis predicting that “there is a significant relationship between self-efficacy and narrative tasks in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy in low proficiency learners” is not confirmed.

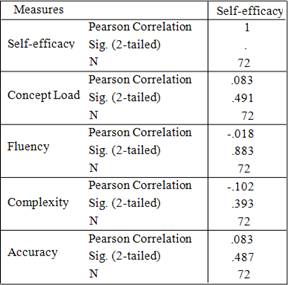

Table 2

Correlation between Self-efficacy and Language Performance

in Personal Tasks

Table 2 provides a summary of the correlations for language performance of low proficiency participants in personal tasks. As can be seen, the significance of Pearson correlation for concept load equals to 0.514, for fluency equals 0.217, for complexity equals to 0.767, and for accuracy equals to 0.559 in low proficiency participants. Therefore, the alternative hypothesis claiming that “there is a significant relationship between self-efficacy and personal tasks in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy in low proficiency learners” is not supported.

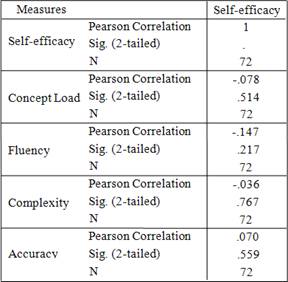

Table 3

Correlation between Self-efficacy and Language Performance

in Decision Making Tasks

Table 3 provides a summary of the correlations for language performance of low proficiency participants in decision-making tasks. As can be seen, the significance of Pearson correlation for concept load equals to 0.535, for fluency equals to 0.858, for complexity equals to 0.685, and finally, for accuracy equals to 0.539 in low proficiency participants. Accordingly, the null hypothesis stating that “there is no significant relationship between self-efficacy and decision-making tasks in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy in low proficiency learners” is confirmed.

Self-efficacy: High Proficiency Learners (Language Performances)

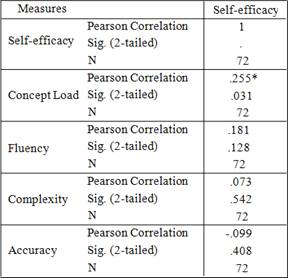

According to Table 4, the significance of Pearson correlation for concept load is 0.002, for fluency is 0.676, for complexity is 0.786, and for accuracy is 0.988 in narrative tasks in high proficiency participants. As a result, the alternative hypothesis predicting that “there is a significant relationship between self-efficacy and narrative tasks in terms of concept load” is supported. Still, the alternative hypothesis claiming that “there is a significant relationship between self-efficacy and narrative tasks in terms of fluency, complexity, and accuracy in high proficiency learners” is not supported.

Table 4

Correlation between Self-efficacy and Language Performances in Narrative Tasks

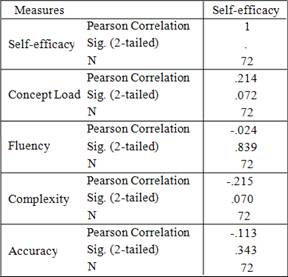

The result of Pearson correlation test is summarized in Table 5. As Table 5 indicates, the significance of Pearson correlation for concept load equals to 0.031, for fluency equals to 0.128, for complexity equals to 0.542, and for accuracy equals to 0.408 in high proficiency participants. In consequence, the research hypothesis predicting that “there is a significant relationship between self-efficacy and personal tasks in terms of concept load in high proficiency learners” is confirmed. On the other hand, the research hypothesis maintaining that “there is no significant relationship between self-efficacy and personal tasks in terms of fluency, complexity, and accuracy in high proficiency learners” is not confirmed.

A summary of the Pearson correlations for language performance of high proficiency participants in decision-making tasks is presented in Table 6. As can be seen, the significance of Pearson correlation for concept load equals to 0.072, for fluency equals to 0.839, for complexity equals to 0.070, and for accuracy equals to 0.343. Hence, the alternative hypothesis claiming that “there is a significant relationship between self-efficacy and decision-making tasks in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy in high proficiency learners” is not confirmed.

Table 5

Correlation between Self-efficacy and Language Performances

in Personal Tasks

Table 6

Correlation between Self-efficacy and Language Performances

in Decision Making Tasks

Discussions and Conclusions

As talked about earlier, to realize the relationship between self-efficacy and the written performance of task types in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy, the Pearson Correlation test was employed. The results confirmed that there was not a significant relationship between self-efficacy and narrative tasks in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy in low proficiency participants. As an alternative, the study recognized a significant relationship between self-efficacy and narrative tasks in terms of concept load but not in terms of fluency, complexity, and accuracy in high proficiency participants.

As well, the present research discovered that there was a significant relationship between self-efficacy and personal tasks in terms of concept load in high proficiency participants, but not in terms of fluency, complexity, and accuracy in both low and high proficiency participants.

Finally, this study enlightened that there is no relationship between self-efficacy and decision-making tasks in terms of concept load, fluency, complexity, and accuracy in both low and high proficiency participants.

In his review article, Klassen (2002) examined and summarized 16 research studies examining the writing self-efficacy beliefs of 6th- to 10th-grade students. In the majority of the studies, self-efficacy was found significant to play a primary role in predicting student writing performance. Moreover, the results of the study by Pajares and Valiante (2001) demonstrated that elementary student’s self-efficacy perceptions predict their writing performance and play the meditational role that social cognitive theory hypothesizes. Student’s self-efficacy beliefs about their own writing capability directly influenced their writing appreciation, perceived usefulness of writing, and essay-writing performance. Besides, Collins and Bissell (2004) established that there was a correlation between self-efficacy and grammar ability.

Thus, the results of this study offer partial verification to be held by the findings of these studies. In fact, the findings are confirmed just in the case of narrative tasks in connection with accuracy of performance in low proficiency participants and narrative tasks relating to concept load of performance in high proficiency participants. The results are not established in the other cases. The reason may be attributed to the different factors such as the participants’ gender, grade level, self-efficacy measure, and scoring writing method, and the interest of the participants in writing. As asserted prior, Klassen (2002) investigated and summarized 16 research articles in his review article. He maintained that several studies found gender differences, with boys rating their confidence higher than girls although their actual performance did not differ. Andrad, Wang, Du, and Akawi (2009) also found gender differences. Grade-level differences in perceived efficacy for writing were found in some studies but not in others. Difficulties with specificity of self-efficacy measures, and with correspondence between measure and criterial task were also found in several studies. The findings of the study by Hidi, Berndorff, and Aniley (2002) showed that children’s genre-specific liking and self-efficacy of writing are closely associated and that both of these factors are also associated with their general interest in writing.

What's more, researchers have reported that self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, constructs, and academic choices, changes, and achievement although, as will be seen, effects sizes and relationships greatly depend on the manner in which self- efficacy and criterial tasks are operationalized and assessed (Pajares, 1996).

References

Andrad, H., Wang, X., Du, Y., and Akawi, R. (2009). Rubric-referenced self-assessment and self-efficacy for writing. The Journal of Educational Research. 102 (4), 287-304.

Arnold, E. (2008). Measurements and perceptions of writing development: Omani academic writers in English. Indonesian Journal of English Language Teaching. 4 (1), 42- 55.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self- efficacy: The exercise of control. United States of America: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Collins, S. J. and Bissell, K.L. (2004). Confidence and competence among community college students: Self-efficacy and performance in grammar. Community College Journal of Research and Practice. 28, 663-675.

Ellis, R. and Barkhuizen, G. (2005). Analyzing learner language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. and Yuan, F. (2004). The effects of planning on fluency, complexity, and accuracy in second language narrative writing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 26, 59- 84.

Errasti, M. P. S. (2003). Acquiring writing skills in a third language: The positive effects of bilingualism. International Journal of Bilingualism. 7 (1), 27- 42.

Foster, P. and Skehan, P. (1996). The influence of planning and task type on second language performance. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 18, 299- 323.

Hidi, S., Berndorff, D., and Ainley, M. (2002). Children’s argument writing, interest, and self-efficacy: An intervention study. Learning and Instruction. 12, 429-446.

Ishikawa, T. (2006). The effects of task complexity and language proficiency on task-based language performance. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 3 (4), 193- 225.

Klassen, R. (2002). Writing in early adolescence: A review of the role of self-efficacy beliefs. Educational Psychology Review, 19 (2), 173-204.

Kuiken, F. and Vedder, I. (2007). Cognitive task complexity and written output in Italian and French as a Foreign language. Journal of Second Language Writing,17, Issue 1, 48-60.

Larsen- Freeman, D. (2006). The emergence of complexity, fluency, and accuracy in the oral and written production of five Chinese learners of English. Applied Linguistics. 27 (4), 590- 619.

Mehnert, U. (1998). The effects of different lengths of time for planning on second language performance. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 20, 52-83.

Mills, N., Pajares, F., and Herron, C. (2007). Self- efficacy of college intermediate French students: Relation to achievement and motivation. Language Learning. 57 (3), 417- 442.

Pajares, F. (1996). Self- efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research. 66 (4), 543- 578.

Pajares, F. and Valianate, G. (2001). Influence of self-efficacy on elementary students’ writing. The Journal of Educational Research. 90 (6), 353-360.

Rahimpour, M. (1997). Task complexity, task condition, and variation in L2 oral discourse. Unpublished PhD thesis, The University of Queensland, Australia.

Rahimpour, M. (2008). Implementation of task- based approaches to language teaching. Research on Foreign Languages Journal of Faculty of Letters and Humanities. 41, 45- 61.

Schunk, D. H. (2003). Self-efficacy for reading and writing: Influencing of modeling, goal setting, and self-evaluation. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19, 159-172.

Schwarzer, R. and Jerusalem, M. (1993). Rev. 2000. General Perceived Self- Efficacy.

Retrieved from http://web.fu-berlin.de/gesund/skalen/language_Selectio/Turkish/General_Perceived_Self-Efficac/hauptteil_general_Percieved_self-efficac.htm

Skehan, P. and Foster, P. (1997). Task type and task processing conditions as influences on foreign language performance. Language Teaching Research. 1, 185- 211.

Skehan, P. and Foster, P. (1999). The influence of task structure and processing conditions on narrative retellings. Language Learning.49, 93- 120.

Yuan, F. and Ellis, R. (2003). The effects of pretask planning and on- line planning on fluency, complexity, and accuracy in L2 monologic oral production. Applied Linguistics. 24, 1-27.

Wiggleworth, G. and Storch, N. (2009). Pair versus individual writing: Effects on fluency, complexity and accuracy. Language Testing. 26 (3), 445–466.

Zimmerman, B.J. (1997). Self- efficacy and educational development. In Bandura, A. Self- efficacy in changing societies (pp.202-231). United States of America: Cambridge University Press.

About the Authors

| Professor Massoud Rahimpour is an honorary research consultant at The University of Queensland in Australia. He holds a M.A in teaching English from Oklahoma City University in the USA and a Ph.D. in applied linguistics from The University of Queensland in Australia. Prof. Rahimpour has presented and published papers in international conferences and journals. He has supervised over 60 M.A and Ph.D theses. Professor RahimpourHe can be reached at: |

Miss. Roghayyeh Nariman-Jahan is an M.A graduate from the University of Tabriz. |

Appendix A:

Tasks given to the participants in each class

Narrative Task

Write a story based on the following picture series

Personal Task

Sending Somebody Back to Turn off the Oven!!

In the afternoon, you are at school, and you have an important examination in fifteen minutes. You suddenly think that you haven’t turned off the oven after cooking your lunch. There is no time for you to go home.

Explain to a friend who wants to help:

How to get to your house;

How to get into the house and get to the kitchen;

How to turn off the oven off.

Decision-making Task

Read the following problem and make sentencing judgment for supposed crime.

At the party, three teenage boys were having a fight with a fourth boy near a swimming pool. They threw him in the water and stood on him until he drowned.

The three boys (and the boy who died) were drunk. They cannot remember anything about the fight in the swimming pool. Another boy at the party said that the fourth boy started the fight.

Appendix B:

General Perceived Self-efficacy Scale

For each of the following statements, please mark the choice that is closest to how true you think it is for you. The questions ask about your opinion. There is no right or wrong answer.

1) I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true

2) If someone opposes me, I can find the ways and means get what I want.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true

3) I am certain that I accomplish my goals.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true

4) I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true

5) Thanks to my resourcefulness, I can handle unforeseen situations.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true`

6) I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true

7) I can remain calm when facing difficulties because I can rely on my coping abilities.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true

8) When I am confronted with a problem, I can find several solutions.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true

9) If I am in trouble, I can think of a good solution.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true

10) I can handle whatever comes my way.

(A) Not at all true

(B) barely true

(C) moderately true

(D) exactly true

Thank you for your cooperation and kindness