| October 2007 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: There is a continuing dialog about alternative methods for teaching different subject matters online. The key seems to be engagement of the student in productive interactions.

Using Comparative Reading Discussions in Online Distance Learning Courses

Jeffrey W. Alstete

United States

Abstract

This article proposes the use of online discussion board-based writing exercises that compare and contrast specific paired readings to enhance the distance learning experience. After examining the background of active learning and the use of asynchronous discussions, specific techniques from current graduate level management courses show how faculty members can create informative conversation threads that utilize existing course related literature and provide the students with opportunities to learn and reinforce deeper understanding of the course topics. The suggested method involves pairing specific faculty selected reading assignments and requiring student participation in graded asynchronous discussions. Results from student feedback comments report very high satisfaction, and supports previous research on epistemological and social aspects of online teaching strategies. Stated learning objectives can be achieved using collaborative techniques such as comparative reading assignments throughout the course term, as part of a multiple assessment methodology.

Keywords: active learning, collaborative learning; comparative reading; distance learning; online teaching, student engagement, asynchronous discussion.

Introduction

As faculty members and educational leaders continue to grapple with the multitude of changes in education and society today, new opportunities for facilitating online learning are emerging. Aspects such as the increased growth in distance learning enrollment, changing student demographics that increasingly include adult learners, expectations that faculty engage learners more actively, and omnipresent instructional technology usage have combined to create strong pressures that educational courses use more than traditional lectures and examinations. Even the relatively widespread use of case studies, simulations, role-playing and other active learning techniques to the educational repertoire have not diminished the continued need for even newer and ever-improving strategies for engaging learners today. In addition, educational institutions and faculty are faced with an increased overall demand for online distance learning courses and programs, encouraged largely by expanding competition, new teaching opportunities and strategies, increased research about distance education, reaching diverse more diverse audiences, and educational globalization (Ferdig & Dawson, 2006; Frank, 2000; Howell, Williams, & Lindsay, 2003). Consequently, this article seeks to explore the background of active learning theories and propose a particular active learning technique using two books that can be called comparative reading discussions. The article begins with a review of the literature to explore background and rationale to establish a conceptual framework of instructional approaches for online courses. The author of the article then proposes a teaching technique that has been used in nine graduate business course sections, and reports student feedback regarding the experience. This proposed tool is not recommended to be the only learning and assessment technique that faculty members should use in distance learning courses. Ideally, this approach is part of a comprehensive pedagogical strategy used by faculty members to engage students in an active learning format in online courses that encourages students to become deeply involved in their learning experience. Other elements can and probably should include regular faculty-led discussions, online exams, writing assignments, and simulation/gaming where appropriate for the goals and stated course learning objectives. At this point, it is important to understand the background and importance of active learning in education today and how comparative reading discussions can be leveraged for courses and programs.

Background and Rationale

Distance learning is having a profound effect on the education field, particularly in the planning, organizing, marketing, supporting, and delivery of post-secondary programs (Howell et al., 2003; Katz, 1998; Lamb, 2000; Lentell & Peraton, 2003; Watts, 2003). These effects often influence faculty members’ course preparation, teaching style, technical knowledge, and contact hours. The online instructional methodologies are becoming more learner-centered, non-linear, and self-directed instead of the traditional model where the teacher is merely a transmitter of knowledge to the student such as through lecture and testing. This coincides with the many traditional campus-based active learning strategies that have become increasingly popular in recent years (Bonwell & Eison, 1991; Meyers & Jones, 1993; Sutherland & Bonwell, 1996). Active learning is commonly described as a teaching technique that connects students effectively in the education method (Prince, 2004). Fundamentally, active learning involves students in performing important educational activities and reflecting on their actions (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). This approach places the responsibility for understanding on the students who are learning (Barak, Lipson, & Lerman, 2006; Keyser, 2000; Niemi, 2002) and enables a broad variety of learning modes in students. It has been stated that directing students to actively decipher questions, discuss what they have learned, and contemplate their thoughts is very valuable for effective instruction and educational outcomes.

New preparation for online courses combined with the increasing expectations by students and institutions for active learning are encouraging faculty members to consider additional techniques and approaches to use in their syllabi. Active learning has been criticized as being especially challenging for courses that have very large enrollments, but is nonetheless necessary to nurture dialogical methods and enable large courses to appear smaller for students (Mattson, 2005). Faculty members are now seeking to create noteworthy encounters in their courses, and use more facilitation or demonstration instead of traditional collegiate lecturing (Levin & Ben-Jacob, 1998). Part of this evolution in the student-faculty relationship is the willingness and ability of the instructor to concentrate on the arrangement and direction of the learning process, and then move aside to allow the students the opportunity to conduct discussions intelligently and more independently. This perceived change of role can be challenging for some faculty members, especially those who may have many years of experience in the more traditional teaching styles that were less focused on active learning methods. Although some argue that this is a false premise for success because skilled faculty are the true key for effective online learning (Markel, 1999). In addition, the growth and development of highly experienced faculty is still possible and can even be encouraged by departments and institutions with proper policies and organizational policies. (Alstete, 2000).

The literature on education and theories of instruction further explains how knowledge can be imparted to students using an objectivist or constructivist model (Hung & Chen, 1999), and that there are social dimensions to consider such as group or individual learning (Benbunan-Fich & Hiltz, 2003) .

In the objectivist model, the ideas are certain and will be instructed directly to students for assimilation. Whereas the constructivist model is based on the notion that knowledge is created by the student learners and that students can learn more effectively when they are involved in the discovery of knowledge rather than being merely instructed (Rovai, 2003). The concept of group-learning contains the premise that students can learn more when they participate in group activities, as opposed to individual learning. Important to note for reading this paper is previous research that specifically examines relationship between the aforementioned teaching approaches and student learning outcomes in online graduate business courses (Arbaugh & Benbunan-Fich, 2006). The research findings in that study reveal that there are significantly elevated results of apparent learning and student satisfaction with instructional method in courses that utilized objectivist methodology reinforced by collaborate learning procedures. Therefore it will be informative to examine if using a particular collaborate learning technique (such as the proposed comparative reading discussions) in a series of online graduate business courses will support the conceptual framework and findings in the previous study.

The collaborative learning approach, which is part of the relatively large movement toward active learning methods, are especially effective in distance learning courses (Bernard, Rubalcava, & St-Pierre, 2000; Levin & Ben-Jacob, 1998). Collaborative learning activities require students to work in teams or groups on the same assignment, reflecting collectively on concepts and resolving issues that are sometimes difficult to grasp. These approaches create a common vision and understanding among the learners, and with the use of distance learning instructional technology, the participants can be at different locations yet still be active in the collaboration. In fact, for some students who may be a bit more hesitant to speak or participate in traditional face-to-face classroom settings, the distance learning setup offers a level of perceived protection that can free their minds for engagement with less concern about shyness and awkwardness when speaking publicly or working collaboratively in person. In addition, using the actual process of collaborative learning is a valuable experience in itself because as students enter a world that is increasingly expecting lifelong learning, on-the job training, retraining, and team-based work duties, their background and ability to function effectively in this kind of group-based communication activity is probably going to be leveraged many times throughout their careers and lives.

Collaborative learning and related styles of pedagogy involve a shift away from the learner as a passive recipient of information, and a correlated shift in the roles of faculty and students (Barr & Tagg, 1995; Levin & Ben-Jacob, 1998). In this schema, the student learners are required to take on a larger amount of duties and accountability for their learning, and not leave it entirely to the faculty members. The students actually develop into energetic examiners and researchers, taking the lead in collaboration with other students and allowing the faculty member to become more of a facilitator. The faculty member is no longer the sole repository of knowledge, and the students are no longer mere empty vessels that need to be filled. Instead, certain assumptions about the experience that students have and their abilities to learn are leveraged more fully in the collaborative learning strategy. There are examples and guidelines available in the educational literature on these approaches, and the techniques for distance learning often include the use of online web-page based discussion boards (Levin & Ben-Jacob, 1998). The faculty member often writes opening questions on these student discussion boards for the learners to read and then become actively involved in. The beginning questions start discussion threads that push or facilitate the students into taking a point-of-view on specific issues related to the course topics that are to be learned. Faculty members who use this approach often start new discussion topics periodically with specified beginning and ending dates. Students are expected to provide a minimal number of participatory comments in the discussion, and may be evaluated on the quality and quantity of their discussion participation by the faculty member.

In addition to general group-based collaborative learning, a particular active learning technique called “talk throughs” is worth examining because it reinforces the concepts behind student elaboration on course topics (Simpson, 1994). The concept in this approach is that after readings have been assigned, students are directed to verbally present ideas that have been read so as to create deeper understanding and memory retention of the topics. Some of the educational and learning theories behind talk-through strategies are that selective allocation (the capacity to encode importance ideas), generation (converting and reorganizing data) and cognitive monitoring are enhanced by conducting a talk on specific themes (Einstein, Morris, & Smith, 1985; Simpson, 1994; Thomas & Rohwer, 1989). As students are forced to think aloud in a traditional classroom setting, it is understandable how they are stimulated into greater understanding, retention of the topics, and appreciation for material learned. However, since distance learning courses are largely conducted asynchronously and often not in a live synchronous format where this kind of talk-through strategy could be easily implemented, other approaches that leverage educational reinforcement concepts need to be used instead. Experienced faculty in these active and collaborative learning strategies have often found that to be effective, transparent instructions should be provided to students about what is expected, because the nonverbal nature of distance learning requires extra attention by faculty to infuse clarity and understanding. The use of paired reading exercises proposed in this paper suggests using collaborative discussions that require students to elaborate on their understanding of the readings could be a fundamental base tool for communicating and expanding the student learning.

Fundamentally, the use of comparative reading assignments involves Socratic questioning to promote critical thinking skills and deep exploration the course topics. This Socratic approach of using questions (although not specifically comparative paired reading assignments questions as proposed shortly) in asynchronous discussion forums has been investigated in previous research and results show that students demonstrate a higher level of critical thinking skills and maintained their critical thinking skills after exposure to Socratic questioning in asynchronous discussion boards (Yang, Newby, & Bill, 2005). Therefore, the use of active learning techniques such as Socratic questioning in collaborative online discussions can be a powerful tool for instructors to use.

Using a Comparative Reading Strategy

Many collegiate textbook publishers today offer supplementary electronic materials for traditional and established college courses. These extremely useful content cartridges for the Blackboard/WebCT, textbook publisher tools, and other e-learning course management systems often provide solid instructional content in the form of course documents, presentations, discussion board topics (often with opening questions already posted), external links, quizzes, and other useful features. However, there are many specialized and advanced course topics for which readily made learning support materials such as this are not yet available, so faculty members are often required to create suitable content for these distance learning courses that use active learning strategies. This need can be somewhat challenging for busy faculty members, yet it can also offer the opportunity for instructional creativity and demonstration of faculty insight regarding the learning process. In addition, faculty members may wish to expand beyond the standard textbook content to emphasize aspects they believe are important for achieving stated learning objectives.

The author of this article has had experience teaching over 50 distance learning courses from 2000 to 2007 in the management department at a medium-sized private college in the New York metropolitan area. These courses were at both the undergraduate and graduate level (MBA) and used the Blackboard e-learning system, in the Fall, Winter, Spring trimesters and two Summer sessions. The comparative reading assignments discussed management here were implemented primarily in nine sections of three advanced graduate level courses on the following topics: 1) Knowledge Management; 2) Managing Business Complexity; and 3) Competitive Intelligence. These are upper-level electives in a respected internationally accredited graduate management program, and the student body is typically mid-level managers who are employed full-time. However, this primarily part-time MBA program also enrolls a mixture of recent college graduates, experienced corporate employees, and visiting students (particularly in the distance learning courses which often attract outsiders) who are from other institutions.

The first step in creating an effective distance learning experience using collaborative techniques such as the comparative reading assignments is to decide upon the course learning objectives. Once the goals have been set, the faculty member can then write the syllabus, select the required readings and prepare the course outline that seeks to achieve these objectives using the best tools and techniques that are available. This faculty member chooses to use a multiple assessment strategy in online courses, which includes required weekly discussions (asynchronous), quizzes, and separate individual writing assignments such as article/book reviews and research papers. Official student feedback from end-of-semester evaluation forms has been very positive, and the learning objectives are achieved using the multiple approach with some variability depending on the course topics and nature of the student body. It should be noted here that advanced graduate electives are normally enrolled with students who are seeking in-depth learning on these very specialized topics, and this self-selection may have some impact on the student performance and learning outcomes. Yet this should probably not preclude the comparative reading assignments for undergraduate or other graduate courses, particularly if there is proper course planning and effective assignment direction provided by the instructor.

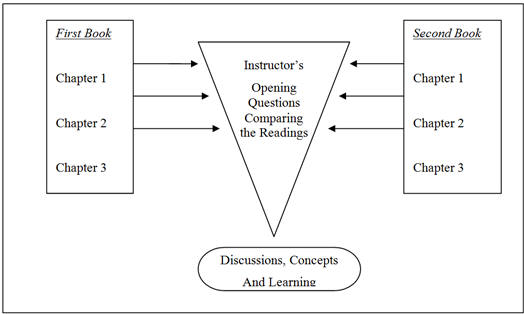

As part of the syllabus creation, the faculty member must choose appropriate reading assignments and/or textbooks for the courses. This is a critical decision step in the preparation of collaborative learning strategies such as comparative readings. Readings and textbooks can be chosen that are similar or quite different in style, content, and reading-level. For the purpose of effective comparative reading assignments this faculty member has found that using books and readings with clear differences in style and content perspective can yield better results. This is because students are encouraged to openly discuss the differences in not only the subject matter, but the way in which the authors treat the subject matter and the way topics are presented in the books. These discussions about and around the topics of learning help solidify the understanding and retention of these advanced topics, and provide useful forums for very interesting and informative discussions by students. Figure 1 shows an illustration of a typical two-part comparative reading structure for a course with two textbooks. The book chapters form the basis for the opening discussion thread questions by the instructor each week, and the students are often asked to explain the differences and/or similarities in the various chapters.

Aside from explaining the differences and similarities in the book chapters, students are also sometimes asked elaborate on one or more topics from certain chapters and then carry on the discussion using concepts from the second book readings (see example opening questions below). The resulting active discussion can become quite lively and engaging, and students are evaluated on the both the quantity and quality of their comparative reading postings. In a typical course with 10 to 20 students, the assignment typically calls for two to three substantive comments posted over the week-long discussion period. Therefore, if the faculty members posts three or four opening question thread discussions for a set of readings, the students are required to write between six and twelve postings during the discussion period. Posting on only one day, or only late the weekly time period, will result in a lesser grade for the student. This strategy strongly encourages the students to become very actively involved from the outset and throughout the learning period of each discussion.

Figure 1 – Comparative Reading Process Illustration

To begin the discussions that examine specific paired reading assignments, instructors should consider the learning objectives, materials being reviewed, student abilities and number of students in the course. Learning modules can be created that divide the objectives into achievable targets that can be measured, and the individual paired assignments can then be appropriately structured. Book chapters, journal articles, academic papers, websites, and related documents could all be used to stimulate the comparative analysis by students, and this is where the instructor has great latitude in using intellectually creativity and judgment. Some examples of opening comparative reading assignment discussion threads are shown below. Note that the proper names below refer to specific books that are being used as textbooks in the courses, and the citation reference is normally not included on the course discussion board (since it is already stated on the course syllabus as required reading material) but is included here as a formality for proper documentation of secondary sources in this paper:

After reading the first chapter of both Tiwana (Tiwana, 2001) and McElroy (McElroy, 2003), what are your initial thoughts on their approaches to KM, and how they are similar and how do they differ?

Do you see a relationship between McElroy's Knowledge Life Cycle and Tiwana's 10 Step Knowledge Road Map? If so, where? or Why not?

McElroy's Chapter 9 seems to have concepts that can and probably should be considered in approaching KM as Tiwana recommends in his Chapter 9 on staffing. How can Tiwana's approach to designing the KM team use McElroy's Learning Drive and PSM Approaches. Explain your thoughts on this.

What similarities and differences do you see in Gharajedaghi's (Gharajedaghi, 2006) Chapter 1 "How the Game is Evolving" and Mitleton-Kelly's (Mitleton-Kelly, 2003) principles of complex evolving systems (CES) in Chapter 2?

Once these opening questions have been posted in the discussion board by the instructor, students will typically begin answering the questions slowly at first. The instructor may intervene in the discussion to assist and guide the discussion forward. Since the students are specifically directed by the instructor to not repeat other students’ comments, but to engage in informative conversations about the thread topics with other students, the ensuing discussions then become quite involved. Students are directed on the syllabus and course website system to write informative and reasoned comments that expand the conversations, and not merely answer the opening question posted by the instructor or to just write “I agree” as responses to other students. The faculty member provides rapid feedback by posting grades on the online gradebook shortly after each weekly discussion is completed. At the end of the course, students in several sections (four) of the courses examined in this paper were asked for the feedback about the comparative reading assignment technique. Overall results were very positive, with 84 percent of the students reporting affirmative learning experiences supplemented with interesting insights about their participation in the course. Some selected examples of student feedback from completed courses on knowledge management and managing complexity in business concerning the strengths and challenges of using comparative readings are as follows:

“The two readings, though different, helped (me) to get a more well-rounded picture when it came to Knowledge Management. Some people preferred one book over the other. I think it was very unique and useful to see the same topic described differently. One problem I saw is not getting into one of the books and relating to it. As I stated before I was nervous about this class in the beginning but enjoyed it very much.” N.P.

“From my point, the course and the subject of KM were quite difficult and challenging itself, so the reading of two different books, with two very different approaches, thoughts, perspectives, etc. gave me the better understanding. It became more realistic, rather than just theoretical. They were - to me - fulfilling each other's gaps, complementary.” M.T.

“The advantages of reading both books with two quite different perspectives are that it allows us to see and understand both authors' opinions on the subject. It also helped me at times that one's point of view would complement or clarify a point that wasn't completely clear by the other author. Throughout the course I was glad to have both books in hand because it definitely gave me and probably the class a broader view of the subject and different approaches to KM. I don't see any problems at all with having the comparative reading technique. I think it only benefits the student's learning process and again it enhances the material and the overall goal of the class. I thought it was a very dynamic class and your constant participation in the discussion boards helped the course to flow more fluently. “ C.B.

“At first I wasn’t enjoying the comparative reading technique because it made the initial part of the course difficult as far as keeping up on readings and material. As the course moved on I began to use both books as a tool to better understand the material covered in the discussion boards. Instead of just having one source of concrete material to use towards the course, we had two and I believe it definitely helped in the material provided and the topics brought up in the discussion boards. The answers varied as well as the opinions and it was definitely easier than in the past to start up a discussion on the board. Sometimes opinions and materials from the books would cross and some confusion was there, but most labeled their opinions and posts accordingly to either McElroy or Tiwana.” W,M.

“I think the discussion boards for the readings provide an exchange of ideas and interpretations of the material. It also allows the students to discuss the concepts discussed in the text and how it has been used in the workplace. There have been points that I may not have picked up in the readings that other students have discussed on the message boards. This has greatly enhanced my learning experience through this course. I think the major challenge of the class structure is that students have to be extremely disciplined and manage their time well in order to get the most of the course (which the students in this class did very well based on the interesting posts throughout the course). For me personally, those courses that are the most challenging, turn out to be the most rewarding in the end.” G.G.

Some of the other positive student comments included some qualification that there were concerns or disadvantages to using the comparative reading strategy approach. Those who students commented in this way also stated that overall they were very satisfied with the experience and were therefore tabulated as positive in the count for this research. However, not all students reported overall positive feedback regarding the use of comparative readings in their course:

“Speak for yourself! I was overwhelmed by the amount of material that we had to read, it was for me, way too much demanding and McElroy's writing, simply put, very scholarly, as he clearly has grasped the English languish. For me a chore.” K.P.

“I guess I should start by saying both books were very difficult to read when in the beginning of the class I had no idea what KM was. Comparing the books is very difficult because the styles were fairly different and while some parts did overlap, they were not in parallel chapters. I think I would prefer to have not done the comparative readings, but instead be asked a thought provoking question on each chapter and have to relate to situations we have encountered in our academic and professional experiences.” M.R.

Nevertheless, using two books can improve the course learning experience and does more than offer students differing perspectives on course content. Students reported that the comparative discussion facilitates informative conversations with others about the differences between the authors, and elaborates different perceptions by students about the readings as well. In advanced courses, the readings are often difficult for students to independently grasp, particularly without in-person contact in a traditional classroom setting with peers and the instructor. Therefore the comparative reading strategy can be an especially valuable tool for online learning, and the findings from the examples in this paper support the previous research on objective group-oriented teaching approaches (Arbaugh & Benbunan-Fich, 2006).

Although these are only selected examples and show the overall positive feedback that was provided publicly in several final week course ending discussions, they are generally indicative of the more comprehensive course evaluations that are performed anonymously and confidentially at the completion of each course. In those official feedback documents, the course evaluation results are only supplied to the faculty member once the official grades have been recorded. Again, those other responses also showed positive student feedback on this learning experience. More importantly, the faculty member found that student performance on regular quizzes and individual writing assignments such as article/book reviews and traditional research papers appear to have been enhanced by the use of comparative discussions throughout the course term. By requiring students to actively discuss, debate, and elaborate on complex topics in the discussions, faculty member can facilitate deeper learning of important topics that are chosen for instruction. This approach is supportive and complementary of the other active learning techniques examined in the previous section, such as the collaborative learning strategies, Socratic questioning, and talk-throughs. Faculty members can decide the best approach for using these tools depending on the course topics, learning objectives, study body characteristics, faculty interests, and other factors.

Conclusion

There are many advantages of using comparative paired reading assignments including greater student involvement, active learning strategy diversification, and overall enhanced learning. When students are engaged with others, either in small student groups or with the class as a whole, they are thereby encouraged directly and indirectly to read the specific assignments periodically, and communicate their understanding and thoughts about the material in an intelligent and informative manner. Student peer influence can support and enhance faculty directions on course assignments, and push the students to new levels of engagement. Experienced students in advanced courses may be especially prone to weariness from repeated styles of teaching assignments, and new approaches that encourage dialogue can assist them in maintaining energy and enthusiasm for the learning process. Faculty members as well, often need additional experiences in their professional endeavors to help maintain professional satisfaction and personal rewards. This author believes that understanding and implementing active learning methods are not only effective in achieving increased student learning and engagement, but are actually intellectually stimulating, professionally rewarding, informative and enjoyable for both students and the instructor. Thoughtful dialogue that is created and facilitated by faculty members and leveraged by their expertise is one additional method to support faculty growth. The general quest by institutions, academic departments, and individual faculty members for engaging and flexible teaching approaches will continue to be expanded as distance learning becomes more common. Therefore comparative paired reading assignments will probably become just one more tool in a useful repertoire of effective syllabi techniques that are available.

References

Alstete, J. W. (2000). Post-Tenure Faculty Development (Vol. 27). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Arbaugh, J. B., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2006). An Investigation of Epistemological and Social Dimensions of Teaching in Online Learning Environments. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(4), 435-447.

Barak, M., Lipson, A., & Lerman, S. (2006). Wireless Laptops as Means for Promoting Active Learning in Large Lecture Halls. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 38(3), 245-263.

Barr, R. B., & Tagg, J. (1995). From Teaching to Learning -- A New Paradigm for Undergraduate Education. Change, 27(6), 13-25.

Benbunan-Fich, R., & Hiltz, S. R. (2003). Mediators of the effectiveness of online courses. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 46(4), 298-312.

Bernard, R. M., Rubalcava, B. R. d., & St-Pierre, D. (2000). Collaborative Online Distance Learing: Issues for Future Practice and Research. Distance Education, 21(2),

260-277.

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. Retrieved May 1, 2002, from www.ed.gov/databases/ERIC_Digests/ed340272.html

Einstein, G. O., Morris, J., & Smith, S. (1985). Notetaking: Individual Differences, and Memory from Lecture Information. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 522-532.

Ferdig, R. E., & Dawson, K. (2006). Faculty Navigating Institutional Waters: Suggestions for Bottom-up Design of Online Programs. TechTrends: Linking Research and Practice to Improve Learning, 50(4), 28-34.

Frank, T. (2000, October). Universities Compete for a Presence Online. University Affairs, 10-14.

Gharajedaghi, J. (2006). Systems Thinking: Managing Chaos and Complexity (2nd ed.). Burlington, Massachussetts: Butterworth-Henemann.

Howell, S. L., Williams, P. B., & Lindsay, N. K. (2003). Thirty-two Trends Affecting Distance Education: An Informed Foundation for Strategic Planning. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 6(3).

Hung, D. W. L., & Chen, D.-t. (1999). Technologies for implementing social constructive approaches in instructional settings. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 7(3), 235-256.

Katz, R. N. (1998). Dancing with the Devil: Information Technology and the New Competition in Higher Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Keyser, M. W. (2000). Active learning and cooperative learning: Understanding the difference and using both styles effectiveley. Research Strategies, 17(1), 35-44.

Lamb, A. C. (2000). Ten Facts of Life for Distance Learning Courses. TechTrends: Linking Research and Practice to Improve Learning, 44(1), 12-15.

Lentell, H., & Peraton, H. (Eds.). (2003). Policy Issues for Open and Distance Learning. Oxford: Routledge.

Levin, D. S., & Ben-Jacob, M. G. (1998). Using Collaboration in Support of Distance Learning. Paper presented at the WebNet 98 World Conference of the WWW.

Markel, M. (1999). Distance Education and the Myth of the New Pedagogy. Journal of Business & Technical Communication, 13(2), 15.

Mattson, K. (2005). Why "Active Learning" Can Be Perilous to the Profession. Academe, 91(1), 23-26.

McElroy, M. W. (2003). The New Knowledge Management: Complexity, Learning, and Sustainable Innovation. Burlington, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Meyers, C., & Jones, T. B. (1993). Promoting Active Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mitleton-Kelly, E. (Ed.). (2003). Complex Systems and Evolutionary Perspectives on Organisations: The Application of Complexity Theory to Organisations. Kidlington, Oxford: Pergamon.

Niemi, H. (2002). Active Learning-- a cultural change needed in teacher education and schools. Teacher and Teacher Education, 18(8), 763-780.

Prince, M. (2004). Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3), 223-231.

Rovai, A. P. (2003). A constructivist approach to online college learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 79-93.

Simpson, M. L. (1994). Talk Throughs: A Strategy for Encouraging Active Learning Across Content Areas. Journal of Reading, 38(4), 296-304.

Sutherland, T. E., & Bonwell, C. C. (1996). Using Active Learning in College Classes: A Range of Options for Faculty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Thomas, J. W., & Rohwer, W. D. (1989). Hierarchical Models of Studying. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association.

Tiwana, A. (2001). The Essential Guide to Knowledge Management. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall PTR.

Watts, M. M. (Ed.). (2003). Technology: Taking the Distance out of Distance Learning (Vol. 94). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Yang, Y.-T. C., Newby, T. J., & Bill, R. L. (2005). Using Socratic Questioning to Promote Critical Thinking Skills Through Asynchronous Discussion Forums in Distance Learning Environments. The American Journal of Distance Education, 19(3), 163-181.

About the Author

Jeffrey W. Alstete is Associate Professor in the Department of Management and Business Administration in the Hagan School of Business at Iona College, New Rochelle, New York. He is the author four books and various journal articles on higher education administration and business management. He earned a doctorate from Seton Hall University, and also holds an MBA and an MS Iona College, as well as a BS from St. Thomas Aquinas College. Dr. Alstete has nearly twenty years experience in higher education, and previously worked briefly in the financial services industry. He has also consulted for higher education institutions and international professional associations. His areas of research interest include distance learning, strategic management, competitive benchmarking, teamwork, faculty development, administration effectiveness, and organizational improvement.