| September 2009 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: Open and flexible learning via the Internet provide educational opportunities for underserved populations and an alternative source of education and training to fit the complex lifestyles of adult learners. This paper discusses key aspects of design and production to ensure relevant and high-quality learning outcomes. The research goal is to evaluate content quality in management education.

Quality in E-Learning Management Education:

The Content Dimension-Factor-Area

Mario Arias Oliva, Leonor González Menorca,

Fermín Navaridas Nalda, Raúl Santiago Campión

Spain

Introduction

A set of activities which tend to be grouped and implemented together by the same firms is called a “mode of innovation”. One involves some form of new-to-market innovation linked to the generation of technology (in-house R&D and patenting). The second involves process modernising and includes, alongside staff training, the use of embedded technologies (acquisitions of machinery, equipment and software). The third is wider innovation, which clusters organisational and marketing-related innovation strategies.

The ability to create, distribute and exploit knowledge is increasingly central to maintaining competitive advantage. Investment in knowledge, defined as public and private spending on higher education, expenditure on research and development (R&D) and investment in software. Improving our knowledge of innovation in firms is crucial for designing innovation policies (OECD, 2008). Knowledge is increasing at such a rate that it becomes obsolete ever more quickly. This is especially true in technical fields. For example, the technical knowledge acquired by students in their first year at university will become obsolete by the time they finish their degree [Davis and Botkins, 1994]. This makes it necessary to analyze knowledge management and the various learning models that support the knowledge operations. Due to this, individual and organizational learning is becoming an increasingly critical success factor because of the need to create flexible structures and strategies that can manage constant change [Dodgson, 1993; Peters y Waterman, 1982; Kanter, 1989; Senge, 1990].

It is imperative to find new learning methods to fulfill new knowledge environmental demands in management education. Advances in information and communications technologies are bringing major changes in teaching and learning methods [Alavi, 1994; Webster and Hackley, 1997]. The incremental transformation model, which served adequately for several decades [Ives and Jarvenpaa, 1996] is no longer enough to cope with new organizational and social learning demands. E-learning emerges as keystone to cope with new conditions.

We can define e-learning as the appropriate application of the any Information and Communication Technology, with special emphasis on the Internet, to support the delivery of learning, skills and knowledge in a holistic approach not limited to any particular courses, technologies, or infrastructures. E-learning has many implications in management education, such as:

- It must find new systems of training-learning where interactivity and bi-directional information will carry more weight.

- Knowledge must be accessible to more people, which will lead to a virtual learning based on multimedia technologies.

- It is necessary to develop customized training programs and, as far as possible, adapted to each need.

Therefore, any person, at any time, virtually anywhere, at any pace will be able to undertake the educational tasks necessary to develop the competences he/she requires. This is the aim of e-learning. This implies a change in the paradigm of education, its concept and administration:

OLD PARADIGM | NEW PARADIGM |

Education is the end | Performance is the end |

The course is only available when it is taught | The course is available when needed |

The classroom is always necessary | The training can occur anywhere |

Education is the same for all the students and is taught at the same pace | Education is customized and adapted to each student |

The trainer is the “boss” | The student is the “boss” |

The contents are regularly updated | The contents are updated every day |

Explanations are based on reference models | Explanations are adapted to the individual needs of the students |

Within this view, the core products of e-learning are technology, services and content (Henry, 2001). Technology includes all ICT[1] including hardware, software and communications that support an e-learning process. Services include strategy and design of your overall e-learning program. And content is the wide range of materials available to the learner. To assure quality in e-learning management education, we should take into account all dimensions. The e-learning methodologies will combine appropriately all dimensions. In this paper, we focus just on the content. Content is a critical variable. In many occasions, traditional learning contents such as Word or PowerPoint files, are considered as content just because they are on an e-learning technological platform. Are these quality contents for e-learning? The aim of this paper is to define a methodology to assure that an e-learning content has reached a standard quality level.

Content Quality: The Creation Process

In order to guarantee quality in any content developed based on ICT, we should distinguish two main phases:

- The creation process before the content is going to be used

- The mechanism to assure that the content, after it has been used, has reached a standard quality level.

We begin analyzing the content creation process. Any process should follow these stages:

1. Identification of training demands or gaps. In the case of higher education, it is also necessary to add the potential “knowledge” it generates (leadership in research or education, specialized publications). In this sense, priority medium/long-term content contexts are necessary either because they are identified as unavoidable or desirable or because the institution has developed a potential worth organizing and exploiting.

2. Acquisition. This stage implies “acquiring” and producing contents. In a first stage,

the process can be “manual” or automated with on-the-shelf specialized tools or by customizing databases. This is an intensive managerial task (contracts, technical and academic requirements of the materials, exploitation of intellectual property rights).

3. Production of digital contents. It covers three main areas: (1) the didactic design inherent to the content that structures it as a material suitable for online training activities; (2) the digital treatment of information: selection of the general format and architecture of the hypermedia: html, dhtml, pdf, flash; (Internet, intranet, CD-ROM, e-mail distribution); (3) the selection of the format of the media (mp3, video streaming, images, animations, etc), application of templates, supporting materials: self-evaluation, glossaries, etc. Note that it is necessary to develop a graphic environment (interface) as intuitive, friendly and simple as possible to facilitate the access to the resources and materials.

4. Organization. Once we have identified, acquired and produced the contents, and considering that they must be as versatile and adjustable to different training programs as possible, we must “tag” or “catalogue” each unit of knowledge according to the variables chosen. Some obvious variables are: author, year of publication, duration, workload; target audience (potential user); prerequisites (a given level of knowledge, diploma or degree). The “tagging” process will allow us to generate “knowledge banks” that will subsequently facilitate the identification and search of materials useful to structure training programs of different nature, educational intensity and duration.

- Publication. It implies making available to the (internal or external) public detailed and varied information on the materials available.

- Distribution. This stage is on the borderline between Knowledge Management and Learning Management. So long as previous stages have been undertaken according to some quality patterns and controls adjusted to the objective of developing virtual learning materials, we should have a large bank of digitalized knowledge suitable for online education. This can be arranged as a system or platform designed to distribute, update, monitor and control the training activities of the students in a given context: the Internet.

The process described presents the transformation of information into knowledge. The following stage implies using this knowledge to stimulate a process of efficient learning.

- The aim of e-learning is to enable people to learn, allowing them to control the training process, studying when they need it, at the request of the student and with a high level of retention and applicability.

- The problem arises when there is a high rate of abandonment in e-learning, when disoriented students are discouraged by a number of issues such as the lack of incentives to learn, problems with technology and poor design of the materials. In principle, students have a clear incentive in higher education (i.e., get a degree), although the following errors must be avoided:

- The lack of relationships among the students; the trainer must try to make the students feel as human beings instead of as software robots.

- Technological problems; it is necessary to watch issues such as the download Arial of the documents, incompatibilities, networks, links, etc.

- The belief that the course can be studied anywhere provided that there is a computer.

- A poor design of the course. Most of the training is not appealing enough and trainers are not prepared to give this kind of courses.

Therefore, higher education institutions are key pieces in the process of production and dissemination of knowledge and will use e-learning to add more value for their students, while providing a more flexible learning. The learning methods proposed in this model imply changes in the definition of the contents and subjects to be studied, as well as in the attitudes and cognitive mechanisms implemented.

Quality Management In E-Learning

Any virtual business model must be based on a new and comprehensive strategy. Therefore, this strategy cannot be confined to some information on the enterprise accompanied by a marketing action: it is necessary to create a new business model with a process of continuous and synchronic feedback that integrates in the new environment a number of related aspects and factors (logistics, production, marketing, human resources, finances, etc.). In the context of online education, we find a similar situation: “traditional” patterns and procedures cannot be accommodated into the new environment, as they need the so-called innovative educational models, a comprehensive strategy both from a managerial and a technical/methodological point of view. The aim is to adjust the objectives (which indeed are the not very different from the traditional ones, that is, make the students learn) to the new circumstances of the technological advances and changes in the habits and ways of working.

But this new conception of the educational space implies a large number of technical, educational and managerial resources that must be homogenized and revised to ensure that the resulting product meets high quality standards. We think that it is necessary to review the main areas and processes where quality management can and must be paramount.

Quality management in e-learning: fields of action

As a Europe-wide study by Massy (2002) highlighted, the main elements of quality perceived by the users are “a smooth running” and “clear explicit principles of pedagogical design adequate to the students, their needs and context”. This study also mentioned that 61% of the interviewees (teaching staff and trainers) gave a “bad mark” to e-learning and qualified it as “bad” or “poor”.

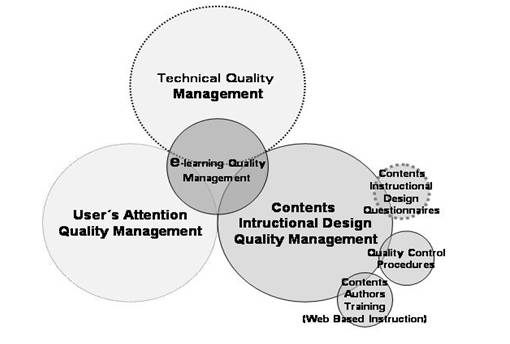

Within the context of quality management, these aspects can be integrated into three different fields of action: first, those related to the technical quality of the materials and the virtual environment where the learning-teaching process takes place; second, the processes of administration of the autonomous and virtual users; and finally, the management of quality in the technical-educational design that must be implemented both in the production of the didactic materials (Knowledge Management) and in the process of the online learning process (Learning Management). This aspect is essential to our proposal and thus will be analyzed in more detail in the following pages. Then, we will describe, briefly, the two first fields of action within the context of quality management in online education.

Quality management in e-learning: technical issues

According to Horton (2000), the technical requirements necessary to design and set up an interface increase the feeling of complexity among its users. Therefore, use of the recommended browser and the possible extensions necessary to display multimedia elements can be insuperable barriers for unskilled users or for those who are not particularly keen on technology. SomeArial, students spend more time learning how to use the tools of the course or looking for a solution to technical problems than studying the subject itself. The broken promises of 24:7 learning as a consequence of failures in the servers or problems of configuration of the Internet accesses damage the confidence of the students. Over and above the innovative state of this changing technology, it is necessary to adjust the internet and computer standards of virtual training programs to the minimum and most easily accessible standard for the users. The provision of a system to help, solve problems and give general information to the students on the telephone seems to be absolutely necessary nowadays.

For Brandon (1997), “the guarantee of the technical quality of online training courses requires a systematic process of revision of each link on the screen in order to detect bugs and problems of referral or execution of the commands that must be reported to the relevant technical staff. Obviously, this refers not only to internal or external hyperlinks, but also to more general issues that imply testing a number of versions of different browsers, operative systems and hardware requirements.

Quality management in e-learning: administrative and customer service issues

Online education occurs in a context unfavorable to learning. The advantages of tele-education is terms of time and space flexibility conflict with the physical context where it is developed: the house or workplace can cause many lapses of concentration due to the freedom of movement and the variety of activities the student can perform at the same time. This real context is always linked to the virtual one, as the Internet can also invite the student to “surf” out of the training program. All these aspects (related to the environment of the learning process and some technical issues) must be taken into account to determine the process necessary to manage quality.

Quality management in e-learning: technical-educational design issues

One of the determining factors of quality in the transformation of knowledge and training products is the educational design. We refer to a whole set of factors that provide the adequate pedagogical and didactic consistency whereby the products are not simple electronic texts but materials properly supported from a temporal point of view, with a balance between learning resources, study aids, activities, distributed academic resources and capable of developing efficient systems of self-assessment. This can be justified in two ways: on the one hand, the attitude of the students who do not understand the arrangement (in terms of learning) necessary to develop an optimal virtual education. This is the result of years of education based on a model focused on the contents (or on the teacher!) that have created an urgent need of “guidance”. On the other hand, and as a logical consequence of all the previous issues, there is a majority profile of online teachers insensible to the need to give some autonomy to the students and develop programs closer to the programmed training than to the exploitation of their autonomy and self-training capacity.

Therefore, online education requires an educational design and production of specific materials adequate to the environment, considering that in the first stages of any traditional training process, the teacher can always adjust the objectives of the course to the real situation of the students (in terms of prior knowledge). Of course, this is more complex and difficult in online education. Besides, the adequate use of the e-mail, forums, mailing lists, etc. as reference and customization tools increases significantly the work of the tutor. The absence of personal contact causes an increased demand of attention on the part of the students. This demand seems to decrease after the third edition of a program or course, as the tutor solves the problems beforehand and anticipates mort of the questions of the students. The crux of the matter might be an inadequate educational approach in the materials of the course that many Arial are a mere electronic version of conventional materials. The design of didactic materials particularly focused on the virtual environment can imply an investment four (4) Arial higher when compared to traditional materials.

The increased commitment to educational activities is transferred to the final user; the lack of immediate and spontaneous feedback, body language, tone, arrangement of the classroom and other elements of a “physical” traditional training, implies that they must be offset, in part, by an increased workload imposed on the student (estimated from 20 to 40 %) and “intense” communication activities: online discussions, resolution of problems in (virtual) groups or individually and communicative actions to enrich the informative channels of the group or the tutor. All this implies that the training of the trainer must be continuous, progressive and up-to-date, which is a fact to be included in expenditure schemes and estimations.

In this sense, there are two elements that might help to ensure the quality of the materials; on the one hand, the production of “Quality Control Materials” with the information necessary to design adequate resources (Piskurich, 2000). There are several examples of suppliers of online training courses that have developed this kind of initiatives among their contributors of training materials (FUR, 2000). On the other hand, there needs to be production of different scales and tools useful to assess with coherence, consistency and comprehensiveness the technical-educational quality of the materials (that is, their adequacy to the environment) provided to the students.

Here is a graphic summarizing the key concepts developed so far. These concepts are also the guidelines to approach our study.

Within the range of possibilities to manage quality in e-learning, we have chosen the analysis of the technical-educational quality of the didactic materials, as we consider that this is the key element of this kind of training and the comprehensive perception on the part of the user. A particular proposal for the tool chosen and its justification are described in the following section.

As Dobbs (2003) said, online training is “thirsty for quality” nowadays.

Evaluation Scale for Virtual University Courses:

Structure And Validation Of The Contents

The scale we describe in this paper has undergone different stages during the elaboration and validation process and accommodates varied input in this final version.

It is a simple Likert range scale extremely useful for the subsequent analysis of the results. Apart from classifying the participants, it includes a constant unit where the difference between the values in the scale is significant. It allows the expert evaluator to express the degree or agreement or any other kind of intensity level for each item in the scale. (Aldrich, 1999, 1996; Barbero, 1993; Chang, 1994; Likert, 1932, López, 1989).

First, and from a theoretical point of view adequate to our object of study, we will try to identify the dimensions that compose the features and basic elements of a virtual university education of quality. We will identify and select the mort relevant descriptors and try to ensure the validity of their content within the contextual framework of our study (that is, we will check to which extent each category represents the features and elements it purports to represent in our research field). To this aim, in a second stage of the process, we will collect the opinions of experts in order to ensure an increased didactic and content validity of the tool proposed.

These experts received the draft version of the scale together with a validation test where they had to assess the following issues:

- the clarity of the instructions;

- the accuracy of the questions;

- the possibility of adding or removing any element;

- a comprehensive assessment, from bad (1) to excellent (5), of the different items covered (dimensions, variables and questions).

As it can be seen in Table 1, the final scale applied revolves around 3 main dimensions. These dimensions gather a number of variables that can be assessed and on which we will base our criteria to evaluate the course. In this sense, and in order to assess all the variables classified, we have adopted a Likert scale with an open field for the experts to enter their feedback on each element of the evaluation (see Annex 1).

Table 1

Structure and levels of the scale used to evaluate virtual university courses

(created by the authors)

DIMENSIONS | VARIABLES | QUESTIONS IN THE SCALE |

PLANNING | · Formulation of objectives | 1 |

· Structure of the contents | 8 | |

· Methodological consistency | 2 | |

· Evaluation of the learning | 10 | |

ADMINISTRATION | · Course guide | 3 |

· Use of the platform | 4, 5. | |

· Flexibility of the program | 6 | |

COMPREHENSIVE | · Fundamental unity | 7 |

· Innovation | 9, 11 | |

· Further possibilities | 12 |

As it can be seen in the Table above, the variables considered in the scale can be classified in three main groups according to their aim:

a. Planning variables:

They gather the pedagogical elements necessary to organize efficient education processes at any level. The first part of the scale includes questions referred to each variable considered in this category:

ü Formulation of objectives: The objectives are the knowledge the students are expected to acquire; this knowledge will be evaluated at a given moment (Doménech, 1999). In this context, properly defined objectives cannot be ambiguous and must describe clearly and accurately the tasks to be performed by the students (thus, they determine the type and quality of the learning produced).

ü Structure of the contents: In order to ensure the quality of the course, it is necessary to select and structure its contents in terms of learning dynamics. Therefore, the initial structure of the contents is determined by educational criteria such as:

§ Sequence: Going from simple to complex things. It is assumed that the trainer must take into account the background capacities and prior knowledge of students.

§ Relation: The initial introduction of the contents (index, roadmap, etc.) must provide a comprehensive picture of the learning process to make the students understand clearly and accurately its continuity and progress. Furthermore, the contents should be structured in an interrelated way, and furthermore, the arrangement of the contents must promote connections or links with other contents of related courses.

ü Methodological consistency: The methodology basically depends on the didactic objectives set and the nature of the course. Thus, the objectives-contents will suggest appropriate strategies to enable the students to attain the expected results. Nevertheless, the methodology must be aimed at the dynamization and autonomous development of the students rather than at a mere transfer of information (Zabalza, 2002).

ü Evaluation of the learning: Note that it is necessary to use varied evaluation tools instead of a single procedure or resource. The variety of evaluation resources enriches and stimulates the quality of the learning. The resources chosen and used to register data on quality will depend on the objective to be evaluated (memorized knowledge, understanding, application, synthesis…), on the approach selected for the evaluation (formative, cumulative…), on the time when it is used (at the beginning, in the middle or at the end of the course), as well as on the relevance and nature of the selected contents.

b. Variables of administration:

They include several variables linked to the teaching activity implemented in the course:

ü Course guide: To fulfill its “guiding role” during the process of teaching and learning, it must be realistic (focused on the prior knowledge of the students, resources and time available, etc.), clear, precise, efficient, understandable and challenging.

ü Use of the platform: It refers to the “academic profitability” of the resources hosted by the system of tele-education: use of tools, configuration, adaptation and customization of the sections available and exploitation by the users.

ü Flexibility of the program: The basic plan of the trainer must foresee and implement any necessary adjustments without detriment to the basic unity of the program.

c. Product variables (comprehensive view):

This group includes the variables related to the pedagogical product (formal appearance, innovation and appeal of the course) and its medium/long-term potential. A comprehensive view can bring to light some neglected aspects that might be a source of concern or issues that might be improved even if they do not any particular problem to implement the course.

ü Fundamental unity: It refers to the general image of the course from a double perspective: the formal image (graphic design, uniformity of color, protocols used, etc.), and the conceptual image (meaning of the icons, value of the glossary, navigability, etc.).

ü Innovation: It refers to the capacity to develop new learning experiences and arrange creative structures of knowledge using the resources of the platform (multimedia/hypermedia) or complementary tools of the author (Light&Light, 1997).

ü Further possibilities: The aim is to collect data on the chances of promoting the medium/long-term technical-educational development of the program or the different types of training contents.

Conclusions

E-Learning is an emerging method in management education. The growing importance of new methods make imperative to transform learning methodologies, but quality indicators for measuring new learning techniques are not very much developed. We define a method to measure quality content, taking into consideration that technology, services, and the whole integration through e-learning methodologies are the final factors to determine the quality of any e-learning process in management education. The Assessment Test created by the taskforce must be administered by an external observer (an expert on this particular learning system) for its correct administration. On the other hand, and in order to collect the information necessary to evaluate the course, this expert will have to analyze each item in the encored test using his/her own professional experiences as a starting point. Therefore, particular attention should be paid to the didactic principles of the design and development of the Study Guide, as well as to the tools used, the relevance of the pedagogical resources implemented in the virtual classroom and the integration of the “physical” didactic part of the learning process. According to the criteria set to evaluate the course as a whole, the maximum score that can be obtained in the test is 26 points[2].

Based on a very useful example, from the scores of 30 subjects taught in a mixed model in the University of La Rioja, it can be concluded that 50% of them have obtained at least one half of the points (that is, at least 13 out of 26). Some of the more relevant data obtained in the evaluation have to do with the level of quality acquired by the education system and to measures or proposals derived from the analysis aimed at improving education on a regular basis. We see clearly that this method is an appropriate tool for our research goal: to evaluate content quality in management education.

References

Alavi, M., “Computer-mediated collaborative learning: an empirical evaluation”. MIS Quarterly (1994), Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 159-174.

Andrich, D. (1989). The application of an unfolding model of the PIRT type for the measurement of attitude. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12, 33-51.

Andrich, D. (1996). A hyperbolic corine latent trait model for unfolding polytomous responses: Reconciling Thurstone and Likert methodologies. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 49, 347-365.

Barbero, M.I. (1993). Métodos de Elaboración de Escalas. Madrid. UNED.

Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas (2001): Plan de acción e-learning, Bruseelas

Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas (2002): Invertir eficazmente en educación y formación: un imperativo para Europa, Brúcelas

Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas (2003): Programa plurianual para la integración eficazmente de las TIC´s en los sistemas de educación y formación en Europa, Brúcelas.

Consejo de Coordinación deUniversidades (2001): II Plan de Calidad en las Universidades.

Chang, L. (1994). A psychometric evaluation of 4-point and 6-point Likert-type scales in relation to reliability and validity. Applied psychological measurement, 18 ( 3), 205-215.

Davis, S., Botkin J., “The Coming of Knowledge-Based Business”. Harvard Business Review (Seep-Oct 1994), Vol. 72, p.170.

Dodgson, M., “Organizational learning: a review of some literatures”. Organizational Studies (1993), Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 374-394.

Doménech, F. (1999): Proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje universitario. Universitat Jaume I

Ellis, R.A., Jarkey, N., Mahony, M.J., Peat, M., Sheely, S. (2007): “Managing quality improvement of eLearning in a large, campus-based university. Quality Assurance in Education.

Henry, P., “E-learning technology, content and services”. Education + Training (2001), Vol. 43, No. 4, pp.249-255.

Ives ,B., Jarvenpaa S., “Will the Internet revolutionize business education and research?”. Sloan Management Review (1996), Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 33-41.

Kanter, R., When Giants Learn to Dance, Simon and Schuter,1989.

Light & Light (1997): Computer mediated support for conventional university courses. Journal of computer assisted learning

Likert, R. (1932). A Technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 140, 1-55.

López Pérez, J. (1989). Las escalas de actitudes (2). En Morales (Comp.) Metodología y Teoría de la Psicología. Madrid. UNED.

OECD (2008), Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2001: Towards a Knowledge-based economy. Washington DC, OECD.

Peters, T. Waterman, R., In Search of Excellence: Lessons Of America’s Best-Run Companies HarperCollins, 1982.

Senge, P., The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Doubleday, 1990.

Webster, J., Hackley, P., “Teaching effectiveness in technology-mediated distance learning”. Academy of Management Journal (1997), Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 1282-1309.

Zabalza, M. (2002): La enseñanza universitaria. El escenario y sus protagonistas. Narcea,Madrid.

About the Authors

Mario Arias Oliva, mario.arias@urv.net is a teacher of organization of companies in the University Rovira i Virgili. It(he,she) investigates in new technologies applied to the company.

Leonor González Menorca, leonor.gonzalez@unirioja.es is a professor of Organization of Companies, in the University La Rioja, and nowadays Director of the Department of Economy and Company. She investigates in quality topics and gives teaching in engineering.

Fermín Navaridas Nalda, fermin.navaridas@unirioja.es is a professor of Education, in the University La Rioja, and nowadays Vicedean of the Faculty of Education. He investigates in educational strategies and has realized studies on applications in virtual environments.

Raúl Santiago Campión, santiagoraul@mac.com is consultant of e-learning and he directed the Foundation of the University of La Rioja, taking charge of the training.

Appendix 1:

Procedure to Control the Quality of the Materials:

Mixed On-Line Model

Indicators:

- Study guide

- Complete sets of tools: learning, evaluation and communication

- Integration of other resources in the classroom

- Impact of the integration on the “physical” part of the learning

- Period where it will be implemented

A. Study guide:

Workload per course: 15 minutes.

1. Does the course have a study guide?

YES | NO |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

If yes;

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

- It is adequate.

- The course does not have a study guide.

- The course has a study guide but it does not follow the model, it is a Word or PDF file that, nevertheless, covers all the sections.

- It follows the model sent to the teachers and all the sections are completed (Appendix II)

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

3. How would you define the pedagogical quality of the “course guide”?

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

1. Bad

3. Poor

5. Excellent

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

B. Complete sets of tools: learning, evaluation and communication:

Workload per course: 45 minutes.

Learning

Contents

4. Are the contents appropriate for the course?

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

5. Is the structure of the contents that of an on-line course?

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

1. The subject does not have contents.

3. The contents are schemes subsequently developed in the classroom.

5. The contents have the structure of an on-line course, with objectives, work methodology, text, summary and bibliography.

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

6. Are the contents completed with interactive elements: links, animations, references to web sites, pictures, etc?

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

1. Never

3. Sometimes

5. Many times/always

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Glossary

7. Is there a glossary?

YES | NO |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

8. If there is a glossary, is it included in the tool itself rather than as a separate document within the module?

YES | NO |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

9. Are the definitions in the glossary clear and properly structured?, do they solve potential doubts about particular terms?

YES | NO |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Assessment

Self-assessment

10. Are there self-assessment questions?

YES | NO |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

11. Are self-assessment questions included in each section rather than as separate documents within the modules?

YES | NO |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

12. Are there enough self-assessment questions? (at least 7 questions per module)

YES | NO |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

13. Are self-assessment questions structured by modules, with a set of questions per module?

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

1. There are self-assessment questions but they are integrated in the module and do not have their own structure, that is, they are no typical self-assessment forms.

3. There are some questions referred to particular modules, but they are unstructured.

5. Each module has its own self-assessment questions in separate self-assessment forms

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Activities

14. Does the module include adequate activities proposed by the teacher?

YES | NO |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

15. If the module includes activities, do they develop the contents of the module?

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

1. The activities are distributed within the module rather than in separate sections.

3. The activities have their own sections, but they are distributed in a confusing way, one does not know what module or chapter they refer to.

5. The activities have their own sections, which are clearly and properly distributed.

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Communication

16. Intensity of use of the communication resources in the platform

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

1. Bad

3. Poor

5. Excellent

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

17. Adequate use of the e-mail

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

1. The e-mail is never used.

3. The e-mail is rarely used.

5. The e-mail is adequately used of the e-mail to go over doubts and the points discussed in the classroom.

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

18. Adequate use of the forum

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

1. The forum is never used.

3. The forum is rarely used and, sometimes,

it is used as a tool to exchange views on issues out of the scope of the subject.

5. The forum is adequately used to clear up doubts and the points discussed in the classroom.

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

19. Level of autonomy and flexibility of the program

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Workload per course: 0.5 hours.

20. General image of the virtual course (icons: are they understandable?, what do they mean?, where do they take?; uniformity of color: is color uniform?, is there a clear pattern?; navigability, etc.)

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Workload per course: 0.5 hours.

21. Level of structure of the learning contents: index and roadmap.

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Workload per course: 0.5 hours per credit.

22. Level of innovation of the contents: multimedia/hypermedia.

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Workload per course: 0.5 hours per credit.

23. Intensity of use of the evaluation resources in the platform.

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Workload per course: 0.5 hours per credit.

24. Intensity of use of complementary tools (for instance, tools of the author)

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Workload per course: 0.5 hours per credit.

25. Technical-educational potential or medium/long-term possibilities of extending the contents

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Remarks: ______________________________________________________________________

Workload per course: 0.5 hours per credit.

Appendix II

Study Guide Of The Course

Study guide of the course | |

Course | |

Title of the course: | |

Description: | |

Prerequisites: | |

General objectives: | |

| |

Coordinator: | |

Counselor: | |

Methodology | |

Description: | |

Content Index | |

Schedule: | |

Evaluation criteria: | |

Basic bibliography: | |

Links: | |

| |

Endnotes

[1] Information and Communications Technology

[2] In the questions where the maximum grade is 1 point, the answer 0 will give 0 points until question 5, which will give 1 point. In the questions where the maximum grade is 0.5 point, the answer 0 will give 0 points until question 5, which will give 0.5 points. In the yes/no questions, “yes” will give 1 point and “no” will give 0 points.