| December 2009 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: Moodle solves a number of problems for potential users. It is open source, which means free; and the code is open so that many organizations around the world are constantly improving this technology. The fact that it can be modified to meet specific institutional needs is attractive organizations where programmer assistance is available. Some administrators argue that they have more confidence in the commercial product and they are willing to pay the costs. Others feel that open source is inferior. They do not realize that the core of IBM server technology is Linux, an open source program. It was adopted after IBM spent millions of dollars developing its own software because Linux had benefited from its attentions from a global community of programmers.

Use Your Noodle to Learn Moodle:

How Moodle can help Saudi Arabian universities create online communities

for collaboration, learning and social knowledge management

Osman Z. Barnawi

Saudi Arabia/Great Britain/USA

Abstract

Although many universities and colleges in Saudi Arabia have incorporated a Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) or Course Management System (CMS) either as an adjunct to traditional EFL courses, usually called a "blended" or "hybrid" course system, or as a tool for their distance education programs. In today’s economy, such programs seem to have some major issues. Specifically, these programs are rigid in the way they can be used and too expensive for colleges and universities to obtain licenses, handle technical support, and build customized learning programs. Also, they are too demanding of designing, programming skills and time. One system that will save time and money for colleges and universities, and help them adapt their programs according to their institutional needs, is Moodle, a free, open source software that does not require universities and colleges to go through a commercial vendor to obtain it. This paper attempts to draw the attention of university and college EFL teachers and educators toward Moodle and its pedagogical potential for creating online communities for collaboration, EFL teaching and learning, and social knowledge management in Saudi higher education community.

Keywords: Moodle, online communities, social constructionist, collaboration, EFL instruction

Introduction

In recent years, it has been a trendy feature for higher education institutes in Saudi Arabia, such as Kind Saud University for Health Sciences, and Yanbu Industrial College, to incorporate a Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) or Course Management System (CMS) as an adjunct to traditional EFL courses, usually called a "blended" or "hybrid" course system, or as a tool for its distance education program (Robb, 2004). Noticeable examples of such VLE and CMS are the integration of smart board, bulletin board, Bodington, IT technology and Internet techniques into EFL classrooms. Nevertheless, in today’s economy such programs (e.g., Bodington or CMS) are not only rigid in the way that they can be used, they are too expensive for colleges and universities to obtain licenses, handle technical problems, and build customized learning programs. They are also too demanding in terms of designing, programming skills and time. Moodle will save these colleges and universities money, time, and help them adapt their programs according to their institutional needs. Moodle is a free, open source software that does not require universities and colleges to go through a commercial vendor to obtain it.

Thus, this paper attempts to draw the attention of university and college EFL teachers and educators toward Moodle and its pedagogical potentials for creating online EFL teaching and learning communities. To achieve this end, I will provide an operational definition for Moodle to familiarize reders of this paper with the Moodle system. I will call Saudi EFL teachers and educators’ attention to the need of incorporating Moodle into their colleges and universities. Specifically, I will argue how Moodle can be an effective tool for creating online communities for collaboration, learning and social knowledge management in Saudi higher education.

I will present the basic installation and major functions of Moodle. Next, I will provide a sample of learning tasks that can be created with Moodle to foster critical thinking and self-voicing in college EFL writing classrooms. I will conclude with possible technical and pedagogical challenges that Saudi teachers and educators may face when using Moodle in conventional EFL classroom instruction.

What is Moodle?

Moodle stands for Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment. It is an enormously flexible and adaptable system for course and learning management. Its development emerged in 2002 as doctoral research by the Australian Martin Dougiamas. On its official website, Moodle is defined as: “a course management system (CMS) - a free, open source software package designed using sound pedagogical principles, to help educators create effective online learning communities” (http://moodle.org/). Since then it has been implemented in more than 193 countries and offered in more than 75 languages.

It is a free, open-source, e-learning, cross-platform course management system, Moodle has widely been implemented in both Eastern (e.g., China, Taiwan) and Western (e.g., Australia, America and British) higher education institutions. Among its international users, it has already become a term of its own synonymous with a software package designed to help educators, teachers, and administrators build full online classes. This can be accomplished in advance or as the course is being taught (Baskerville, & Robb, 2005; Brandle, 2005;Wu, 2008). With its enormously flexible and adaptable features, Moodle can be incorporated in a variety of ways depending on the needs and capabilities of a particular university or college. This suggests that Saudi universities and colleges have a variety of choices for incorporating Moodle into their conventional EFL classroom instruction. These range from simple classroom management to fully interactive e-learning, or a combination of the two. Moodle is a free online course management system aimed at fostering social interaction between (Saudi) teachers and their students and among the students themselves. Questions that need to be addressed include: “why do Saudi colleges and universities need to incorporate Moodle into conventional classroom instruction?” And “What are the pedagogical outcomes for incorporating such innovation?” I will tackle these questions in the next section.

Incorporating Moodle into the Saudi Arabian Higher Education Community

In cultures such as Turkey, China, Japan, and Saudi Arabia, social values such as authority, social harmony and deference to the elders and teachers are highly valued. As a result, traditional methods of EFL teaching and learning that are teacher-centered still prevail in academic settings. Also, most university and college EFL teachers believe that a classroom in which they are dominant will guarantee pedagogical success. As the philosophy of teaching and learning in the Saudi context inculcates passivity, dependence, a priori respect for authority and unquestioned attitudes. EFL students in classroom settings perceive their teacher as a figure of authority, the only source of knowledge, and their teachings should not be questioned. As a result, interaction between teachers and their students, and among students is limited, and debate is often absent as a source of knowledge construction. Consequently, most college EFL students lack skills such as self-assessment, monitoring their own process of language learning, and have little motivation to undertake their learning outside of the classroom.

It is assumed that language learning is a lifelong endeavor in which teachers should become aware of the worth of independent learning both inside and outside the classroom, so that students can gain the habit of learning continuously and maintaining it after they have accomplished their formal study (i.e., college or university). More importantly, knowledge is socially and discursively constructed and co-constructed. “Teaching is a public, socially-constructed role, subject to the perceptions and expectations of learners, colleagues, schools and the community” (Roberts 1998 p. 309). This notion of social constructivism has shaped “pedagogical transformation in a sense that student-centred, collaborative task-oriented, and engaged learning substituted traditional instructions where passive learning and teacher centeredness prevail” (Barnawi, 2009, p.52). Thus, it is imperative to foster the autonomy of Saudi EFL students by incorporating educational technologies that create an environment of interaction and collaboration both inside and outside the classroom.

Moodle is a free open system and a low cost solution for effective e-learning. Moodle, with its emphasis on constructivist and social constructionist approach to education, offers mediating tools which help it to achieve the objectives of a social constructivist-based classroom in many ways. One is its enormous flexibility in which teachers, educators and administrators can incorporate it into their classrooms according to the socio-cultural, linguistic and political needs of their own institutions (Baskerville, & Robb, 2005; Brandle, 2005). More importantly, it integrates many different systems like webpage, wiki, blog, and bulletin board into a rich learning experience.

In addition to the above benefits, Moodle transforms traditional teacher-centered pedagogy into a dialogic learner-centered pedagogy - a pedagogy whereby teacher and learner become mediators in co-constructing and navigating knowledge construction. For example, when students comment on entries in databases or work collaboratively in a Wiki, they can construct, de-construct, re-construct, and co-construct knowledge with teachers and peers. Furthermore, Moodle makes all language learning resources available to all students and allow them to explore and investigate beyond their subject (i.e., English). It also allows teachers and administrators to open up parts of their educational system to other institutions (joint courses, joint research projects) so that they can co-construct the knowledge, i.e., language learning materials can be in a centrally accessible repository, sharable and searchable by other universities and colleges. Moodle offers quality, reliability, accuracy, accountability, collaboration, and greater communication to its users as it helps the education world set, follow, and maintain standards.

A thorough evaluation of the pedagogical outcomes of Moodle conducted by Goba, Nimrod, and Gareth (2004) conclude that: (i) Moodle is a free open source that teachers can use it according to their institutional socio-political, linguistic and cultural needs, (ii) it offers a collaborative learning space where students and teachers, and students among themselves can meet, read, and write. In this way, students and teachers become critical co-investigators in dialogue with each other, i.e., all teach and all learn, (iii) it allows teachers to easily save and archive many of the mechanics of classroom operation—such as assignments, activities, scheduling, and quizzes, (iv) it reaches its full potential only if it becomes a place where data can be shared and processed by automated tools as well as by people (i.e., semantic Web), (v) it is a self-explanatory program in which users, by clicking the help option, can find answers for all their questions, and (vi) it is easy to install on any computer, i.e., Windows, Macintosh or Linux and the Interface can be switched to more than 50 languages.

From the above discussion, it could be argued that Moodle has great potential to successfully accommodate teachers, educators, and a wide variety of teaching structures. It does not pigeon-hole EFL students into modules and courses, and it embraces interdisciplinary studies and variety of student roles. Having discussed the pedagogical assumptions for infusing Moodle into EFL classrooms, we must also ask technical questions as to how well Moodle runs on different computers and operating systems.

Functionality of Moodle

Unlike web-designing tools that require a specific features and operating systems, Moodle is easily and quickly installed on PCs and Apple computers and it can be scaled up to accommodate a large user base. It runs without modification on Unix, Linux, FreeBSD, Windows, Mac OS X, NetWare and any other system that supports PHP computer scripting language (e.g., web host providers). In early versions of Moodle (1.6 and 1.7) MySQL and PostgreSQL were the only feasible options. The version released in January 2008 (Moodle 1.8.4) contains improvements that make Moodle more flexible and stable (Baskerville, & Robb, 2005; Brandle, 2005;Wu, 2008). There are four easy steps to get a Moodle system.

1. Determine the available server, IP address, domain name, and database tools: for example: (Apache) +MySQL+PHP+ Moodle.

2. Convince decision makers at your college or university about the pedagogical potential of Moodle and how it will enrich conventional classroom instruction.

3. Have users download the software from Moodle.com to set it up on their machine.

4. Find a free host.

The author’s Moodle system – Open source for Educators – is free. Subscription-based media libraries, external web links, and other commercial software products can potentially be integrated into Moodle courses according to the needs of your college or university progams.

Major features of Moodle

One of the most distinctive features of Moodle, as mentioned earlier, is its enormously flexible and adaptable nature. Thus, it can be incorporated in a variety of ways depending on your institution’s needs and capabilities. With its template-based CMS, both students and teachers can add content. Moodle’s navigation interface is user-friendly and intuitive. EFL teachers with limited computer literacy can use it to build dynamic and collaborative EFL learning communities. Some of Moodle’s major features related to creating online communities for collaboration, language learning and social knowledge management are introduced below.

Layout

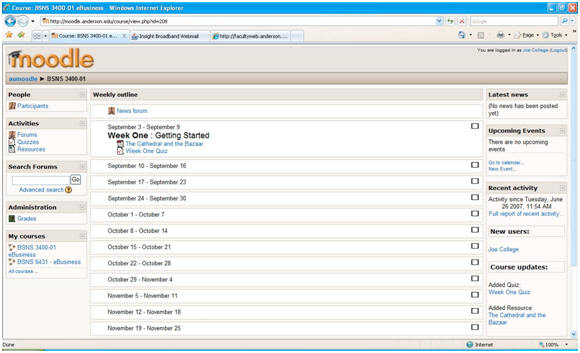

Figure 1 below shows a typical Moodle screen. All elements on the page are template-based so that EFL teachers can easily add, modify, reposition, or delete blocks of text and graphics. Resources and special functions selected for that course or college are displayed on both sides of the screen (Robb, 2004). Each section in a Moodle course has lessons, quizzes, assignments, and forums that are linked to a built-in grade-book. All resources on the page can be individually organized, and elements within each section can be easily moved around or hidden.

Figure 1: Moodle home page showing menu and resources.

Course Management System (CMS)

Moodle, by and large, is a powerful and miscellaneous CMS and EFL teachers can effectively trace and manipulate its functions to make their lessons, assignments and quizzes (e.g., reading and writing) and set time-or-password-restrictions. Moodle keeps automatic log reports of each student’s work and the teacher knows not only when students have completed or uploaded a writing assignment, but how much time was spent on assigned tasks or quizzes as shown in sample 2 below. Furthermore, EFL teachers can set deadlines or timeframes for students to complete assignments and restrict access when the deadline has passed. Students can look up their grades after the teacher downloads them (e.g., in Excel format). They can trace their daily or weekly assignments and quizzes on a calendar by moving the cursor over a given day to display assignments and quizzes. Moodle is an interactive management and communication tool to increase effectiveness, quality, reliability, accuracy, accountability, collaboration, and communication for both teachers and students.

Content

While using Moodle in EFL instruction, teachers have a wide range of choices to integrate any kind of resources into it. For instance, they can include any kind of text-based or html-formatted documents, multimedia resources such as graphics, video or audio (e.g., MP3 files), PowerPoint, or Flash-based applications. Additionally, EFL teachers can link and upload their lesson tasks within Moodle to one's server or these are available on the Internet. In this way, students can easily access the content-based resources by using Moodle both inside and outside of their colleges or universities.

Assessment techniques

Interestingly enough, Moodle allows for a wide range of assessment strategies (Robb, 2004; Wu, 2008). Among these strategies, the quiz module comprises fill-ins, multiple-choice in which more than one answer can be chosen, true-false, matching, short-answer (exact matching).

In the words of Brandle (2005), the workshop module is also seen as another wonderful evaluation strategy that is designed on the basis of peer assessment. All of these assessment types (e.g., workshop, fill-ins, multiple-choice) can be time and password restricted, and allow for limited or multiple re-submission. This will further help EFL teachers to trace student performance both inside and outside the classroom. As mentioned earlier, Moodle is designed from a social constructivist learning perspective. It provides useful tools such as Wikis, forums, chats, blogs, and workshops so that EFL teachers can implement different formats of social interaction and collaboration into their teaching. For instance, students can be divided into subgroups (either visible or separate), interact with each other synchronously in chat activities, and engage in asynchronous discussions in Wikis and forums. The teacher can save all the written dialogues in chat rooms for later reference (e.g., collaborative feedback and critical reflection). Students often complain about the lack of enough feedback, in conventional classroom settings. Through asynchronous discussions in Wikis and forums, learners are able to construct, de-construct, re-construct and co-construct knowledge (e.g., collaborative feedback in EFL writing). EFL teachers can post persuasive writing along with online collaborative feedback tasks in the assignment section of Moodle. This offers a social constructivist-based learning space where students and teachers, and students among themselves can meet, read, and write. In this way, the students and teachers will become critical co-investigators as they dialogue with each other, i.e., all teach and all learn. One possible example of persuasive writing task is depicted below.

Figure 2: Student data in Learning Management System.

Cooperative learning

Figure 3. Sample of learning tasks that can be created with Moodle:

Fostering critical thinking and self-voicing in college EFL writing classrooms

Persuasive writing

The above persuasive writing task should help a student-writer gain critical thinking and self-voicing skills in EFL. Such tasks will help the student-writer brainstorm, identify, analyze, evaluate, construct and support arguments using his or her prior knowledge and experience and other sources of information. They will also help in self-assessment and in monitoring his or her own learning process. These tasks engage the student-writer with discourses that are both real and significant in his or her daily lives. Such tasks urge the student-writer to work enthusiastically to meet the real needs and expectations of a community audience by taking his or her writing beyond the classrooms.

The student-writer may experience difficulties in identifying or choosing a specific organization or identifying problem to write about. In this regard, I agree with Yarbrough’s (1999) assertion that “in most cases [college or university] students already perceive problems they want to be able to solve and have questions they want to be able to answer” (p. 240). If it appears that a student-writer could not recognize a specific organization or problem, scaffolding by peers and teachers may be necessary.

Online collaborative feedback tasks

Indisputably, treatment of EFL writers’ errors is a challenge for writing teachers in a face-to-face classroom or an online-based course. Treatment of EFL writers’ errors is controversial in that some researchers perceive it as an ineffective strategy. Those who argue against feedback contend that it is not effective and may de-motivate students to write because students blame themselves as ignorant or incapable writers (e.g., Polio, Fleck, & Leder, 1998; Truscott, 1996). They further argue that providing feedback on writing does not develop language accuracy in student writing long-term. Students continue to make language mistakes in subsequent drafts after they received considerable feedback in face-to-face classroom or an online course.

On the other hand, those who argue for feedback in students’ writing (e.g., Bitchener, 2008; Ferris, 2008) maintain that although providing students with feedback “in the form of written commentary, error correction, teacher-student conferencing, or peer discussion” (Hyland & Hyland, 2006, p. xv) may not help students to avoid making mistakes, it can raise students’ awareness of correct writing. In this regard, I believe as other researchers (Ferris, 2008) contend, mistakes always take place while learning foreign or second language writing. Not everyone can avoid making mistakes in writing although she or he may have a high level of language proficiency. As writing teachers, we cannot assume that students will automatically notice or realize their gaps or problems without social mediation through teacher or peer feedback. Therefore, it is imperative to seek possible strategies such as those offered in Moodle to help student-writers improve their writing accuracy and fluency.

Moodle is, without doubt, an excellent tool to foster online-based collaborative feedback communities. In Moodle, student-writers can easily communicate with each other synchronously and asynchronously and share their writing online with peers and teachers. Both teachers and students have a dynamic environment to interact with each other, to give/get support and build rapport through discussion and negotiation about gaps or ways to improve their writing. When students collaboratively find problem(s) in draft documents, they provide different feedback strategies to their peers. For example, one student may be good at identifying form problems (mistakes in grammar and vocabulary); another may be good at recognizing structural problems in content or logic. Collaboration allows students to support one another in recognizing problems. Second, online collaborative feedback stimulates critical thinking. If students have different interpretations of gaps or problems, they will negotiate them by expressing their ideas or arguments, and in turn they will justify such arguments with lines of evidence. This process helps students to develop critical thinking by noticing gaps or problems in writing. Third, this task helps students be aware of their own or their peers’ drafts, which in turn will help to enhance awareness of writings that may present difficulties for a reader.

The above tasks have enormous benefits with regard to critical thinking and self-voicing skills in writing/composition classrooms. The negotiation between peers and teachers encourages students to do critical discussions for finding solutions and improving their writing. Moreover, conflict or disagreement in that negotiation provides impetus for students to re-examine their language use, arguments, organization and clarity in their writing (Swain & Lapkin, 2002).

Challenges to using Moodle in EFL teaching and learning

Undoubtedly, innovations such as Moodle do not automatically spread in the contexts where they are supposed to be adopted, but need to be adequately endorsed and communicated (Barnawi, 2009; Rogers 1995; Lepori, Cantoni & Succi 2003). As Baylor and Ritchie (2002) convincingly argue, “regardless of the amount and sophistication of technology, faculty members must have the skills and knowledge to use it” (p.398). Therefore, a series of workshops on the use of Moodle, from both a technical and pedagogical point of view, is necessary in order to equip Saudi EFL teachers and administrators with skills and knowledge to implement these technologies.

Although the Moodle website provides detailed instruction on how to set up Moodle in EFL classroom, some technical issues may require a teacher to possess a high-level of computer literacy skills to address them. Wu, (2008) points out that EFL teachers “should have a high-level computer as a server and know how to install database software, such as MySQL or Microsoft SQL, on the same server, which is quite a formidable challenge for most English teachers without the help of technical support. Even if IT professionals help English teachers install Moodle and database software, English teachers may also feel frustrated debugging computer- or Internet-related problems that teachers of the web-based English classes may face” (p.53).

This suggests that, in addition to the series of workshops, an online module about the technical features of Moodle should be developed and put at the disposal of e-Courses users so that teachers can refer to them when necessary. More importantly, one-to-one assistance with ad hoc modules should be offered to assist teachers who need further assistance in using Moodle in their EFL classrooms.

In conclusion, Moodle, with its emphasis on constructivist and social constructionist approaches to education, offers media tools to achieve the objectives of a social constructivist-based classroom. It is a platform to access and manage collaborative materials for teaching and learning online. It is a platform where teachers and students can learn together. Innovative teachers should not wait for their institutions to install a perfect CMS; instead they should join the Open Source movement to construct and co-construct knowledge using Moodle. More importantly, they should join the Moodle online community of be updated by participating, interacting, and sharing their experiences, needs and interests. This will further help them think locally and act globally. This is because “the key to successful use of technology in language teaching lies not in hardware or software but in humanware” (Warschauer & Meskill, 2000, p. 307), instead in participation and interaction to experience and feel that you are among like-minded people who share the same curiosities, needs and interests.

Reference

Barnawi, O. (2009). The Internet and EFL College Instruction: A Small-Scale Study of `EFL College Teachers’ Reactions, International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 6 (6), 47-64.

Baskerville, B., & Robb, T. (2005). Using Moodle for teaching business English in a CALL environment. PacALL Journal, 1(1), 138-151.

Baylor, A., & Ritchie, D. (2002). What factors facilitate teacher skill, teacher morale, and perceived student learning in technology-using classrooms? Computers & Education, 39, 395–414.

Bitchener, J. (2008). Evidence in support of written corrective feedback. Journal of Second Language Writing, 17(2), 102-118.

Brandle, K. (2005). Are you ready to “MOODLE”? Language Learning & Technology, 9, 16-23.

Ferris, D. (2008). Feedback: Issues and options. In P. Friedrich (Ed.), Teaching academic writing, (pp. 93-124). London: Continuum.

Goba, S., Nimrod, A. and Gareth, S. (2004). “Online Course Material Interoperability and tutorial Module for Moodle.” Technical Report CS04-24-00, Department of Computer Science, University of Cape Town. Available at: http://pubs.cs.uct.ac.za/archive/00000179/01/Technical_Paper.pdf

Hyland, K., & Hyland, F. (2006). Feedback in second language writing: Contexts and issues. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lepori, B., Cantoni, L. & Succi, C. (2003). The introduction of eLearning in European universities: models and strategies. In: Kerres M., Voss B. (eds), GMW03, Duisburg, Germany.

Moodle: Teacher Manual. Available at: http://moodle.org/doc/?flie=teacher.html

Polio, C., Fleck, C., & Leder, N. (1998). ‘‘If only I had more time:’’ ESL learners’ changes in linguistic accuracy on essay revisions. Journal of Second Language Writing, 7(1), 43–68.

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: The Free Press.

Robb, T (2004). Moodle: A Virtual Learning Environment for the Rest of Us. The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 8:2. Available at:

http://tesl-ej.org/ej30/m2.html

Roberts, J. (1998). Language teacher education. London: Arnold.

Swain, M., & Lapkin, S (2002) Talking it through: two French immersion learners’ response to reformulation. International Journal of Educational Research, 37, (3), 285–304.

Truscott, J. (1996). The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes. Language Learning, 46(2), 327–369.

Warschauer, M., and Meskill, Carla (2000). “Technology and Second Language Learning.” In J. Rosenthal (Ed.), Handbook of Undergraduate Second Language Education (pp. 303-318). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Yarbrough, Stephen R. 1999. After Rhetoric: The Study of Discourse beyond Language and Culture. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Wu, W. (2008). The application of Moodle on an EFL collegiate writing environment. Journal of Education and Foreign Languages and Literature,7(v), 45-56.

About the Author

| Osman Z. Barnawi is a Ph.D. candidate in Composition and TESOL at the Department of English, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA. He is an EFL/ESP lecturer at Ynabu Industrial College, Saudi Arabia. He has a M.Ed. in TESOL from the University of Exeter, U.K. His recent publications are The Construction of Identity in L2 Academic Classroom Community: A small Scale Study of Two Saudi MA in TESOL Students at North American University. The Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 5(2), 62-84. The Internet and EFL College Instruction: A Small-Scale Study of EFL College Teachers’ Reactions, International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 6(6), 47-64. His research interests include second language writing, second language learners’ identities, extensive reading, ESP program evaluation, educational technologies and teacher language education. His email address is: albarnawim@hotmail.com |