| March 2011 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: This study reminds us that, like audiovisual aids, the web is initially a supplement for traditional face-to-face-teaching. Our first attempts at distance learning emulate the lecture-demonstration-discussion model. Students feel isolated and interaction is minimal. As advantages of the web become apparent - anywhere-anytime learning; greater opportunities for student-to-student and student-to-teacher interaction; and extended learning resources - we graduate to new concepts of communication, teaching and learning where the student has greater flexibility and control of the learning process.

Examining the Levels of Web-ness of Online Courses

at the University of the South Pacific

Javed Yusuf

Fiji

Abstract

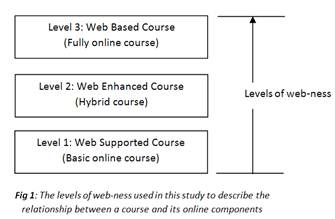

The University of the South Pacific (USP) is a regional university serving twelve Pacific island nations with 14 regional campuses around the Pacific. USP uses a range of media such as face-to-face, print materials, online learning management systems (Moodle), audio/audiographics and video conferencing, audio/video tapes, CDROMS and DVDs for the delivery of its courses with an institutional goal of delivering all of its courses through the web. It uses Moodle, a free and open source learning management system. The level of “web-ness” of courses using Moodle varies among courses from web supported (basic), to web enhanced (hybrid) and to web based (fully online).

This study examines all USP courses that utilized Moodle in Semesters 1 and 2 of 2010, classifies and quantifies them according to their level of web-ness. The main research question was how many USP courses used Moodle as a web supported, web enhanced or web based classroom. Results suggest that while there was slight increase in the overall use of Moodle at USP moving from Semester 1 to 2, most courses still utilized Moodle for basic course support. The paper then follows through with discussions on findings and recommends options for future research.

Keywords: Moodle, USP, levels of web-ness, web supported, web enhanced, web based, online learning and teaching, learning management system

Introduction

The University of the South Pacific (USP) is the only regional university of its type in the world. It serves twelve Pacific island nations (Cook Is., Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Is., Nauru, Niue, Solomon Is., Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu and Samoa) with 14 regional campuses around the Pacific. The main campus is located in Suva, Fiji. It offers an average of 487 courses per semester in either face-to-face and/or distance and flexible learning mode. These courses are delivered using a range of media such as print materials, learning management systems (Moodle), audio/audiographics and video conferencing, audio/video tapes, CDROMS and DVDs with an institutional goal of delivering all of USP’s courses through the online mode.

Since 2001, USP have been utilizing WebCT and Plone-based EDISON systems as its Learning Management System (LMS). In 2007, the University’s senior management selected Moodle as the single LMS for USP. Moodle is a free and open source LMS which is being widely adopted by thousands of educational institutions and has an ever growing worldwide community of developers and users. Since its inception at USP, Moodle have become the most used and is an essential system of the University with approximately 7500 users daily (USP Learning Systems Manager, personal communication, January 18 2011). Use is anticipated to exponentially grow even more in 2011 after a directive from the University’s Deputy Vice Chancellor (Learning, Teaching and Student Services) mandating that all lecturers use of Moodle as part of their course delivery in 2011. However, the levels of web-ness of courses using Moodle varies from basic web supported courses to blended (hybrid) web enhanced and fully web based courses.

This study examines all the courses that utilized Moodle in Semesters 1 and 2 of 2010, classifies and quantifies them according to their level of web-ness. For this study, three levels of web-ness were considered: web supported (basic), web enhanced (hybrid) and web based (fully online). This is further explained in the literature review section of this paper. The main research question was how many USP courses used Moodle as a web supported, web enhanced or web based classroom. It elaborates on the methodology and checklists that were employed to determine the level of web-ness of a course in Moodle followed by findings and results. Discussion of findings tries to identify and rationalize obvious trends and recommends topics for future research.

Literature Review

The recent advances in technologies, in particular the advent of LMSs, have made it easier to provide online learning and teaching experiences and becoming “increasingly important part of academic systems in higher education” (Morgan, 2003). Most universities have adopted some kind of LMS (Falvo & Johnson, 2007; Narwani & Arif, 2008). However, opinions are divided as to what is the best learning environment online, whether it is fully web based or web supported Wu (2004). Schmidt (2001) states that a combination of online and traditional classroom instruction has become the most popular way to use internet’s learning and teaching tools which is the hybrid or blended delivery where the web is used to enhance the face-to-face learning and teaching. As Wu (2004) noted, most of the time, the way the web is utilized in a course is not clear to learners or even lecturers. Thus, learners and lecturers are not able to fully understand their relationship between the use of web (LMS) and the course learning outcomes. For this study, the different types of relationships between a course and its online component are considered as the ‘levels of web-ness’. The level of web-ness indicates how the web is used in a course and what percentage of learning and teaching occur using the web. Because the University of the South Pacific (USP) does not have an institutional definition to describe levels of web-ness in its courses, this study distinguishes three levels of web-ness: web supported (basic), web enhanced (hybrid) and web-based (fully online).

The first level, a web supported course, makes a very basic use of the learning management system. Basic materials about the course and/or lecturer are placed on the web for ease of access to course information. Use is mainly for knowledge presentation and to make course documents, lectures, and other static information, available to learners (Bento & Bento, 2000), and to link to class management resources such as course announcements (Woods, Baker & Hopper, 2004). It is important to note that the use of web in a web supported course is neither relevant nor necessary to achieve any explicitly stated course learning outcomes (Gandell, Weston, Finkelstein and Winer, 2000) and thus almost 95% or more of learning and teaching occurs face-to-face. For this study a web supported course, at minimum, contained the following elements:

§ Course administrative information: Course outlines and guides, course goals and learning outcomes, etc.

§ Lecturer information: Lecturer contact details, information about the teaching team, etc.

§ Course notes – handouts (Word or PDF files), PowerPoint notes, etc.

§ Additional resources – readings, reference guide, links to external web, etc.

§ News forum - course news and announcement forum.

The second level of web-ness, a web enhanced course, makes use of Learning Management System (LMS) tools to incorporate various online activities, enhance learning, and support course management and delivery. According to Colis and Moonen (2001), this model of course delivery is a hybrid of traditional face-to-face and online learning so that instruction occurs both in the classroom and online, and the online component becomes a natural extension of traditional classroom learning. Previous studies suggest that this hybrid model of course delivery holds significant benefits for learners and lecturers (Bento & Bento 2002; Black, 2001; Papo, 2001; Saunders & Klemming, 2003; van de Ven, 2002; Woods, Baker & Hopper, 2004) and Ge, Lubin, Zhang (2010) states that increasing number of universities utilize LMSs for blended or hybrid learning. Gandell et al. (2000) posits that the use of LMS in a web enhanced course is integral and relevant, contributing to the achievement of some of the course learning outcomes and thus could have a fair amount of impact on learner’s learning performances. From a course design and delivery perspective, a hybrid course can lie anywhere between the continuum anchored at opposite ends by fully face-to-face and fully online learning environments (Rovai & Jordan, 2004) and “finding the right degree of web enhancement is a great challenge” (Schmidt, 2002).

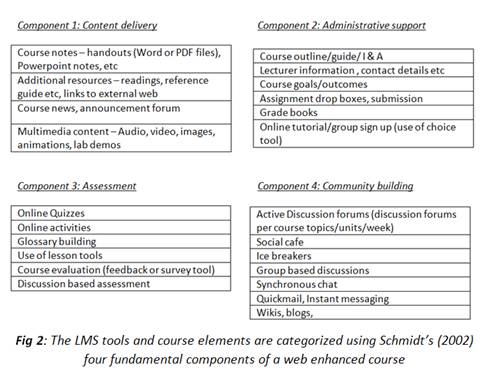

This study assumed that in a web enhanced course, most course activities were occurring face-to-face but certain activities were online using the LMS tools. Schmidt (2002) describes four fundamental components of a web enhanced course; administration, assessment, content and community. This description was used by this study to determine if the level of web-ness of a course to be web enhanced (hybrid) as shown in Figure 2. In this study a web enhanced course contained at least 60% or more elements of each component in conjunction with significant face-to-face components.

Finally, the third level of web-ness, a web based course or a fully online course, is where all the learning and teaching experiences occur on the web. There is no face-to-face element and there is a significant use of LMS tools. All course materials, instructions, discussions and assessments are done online (Mann, 2000). The web is both relevant and necessary for achievement of all course learning outcomes, and thus has a great impact on learner’s learning performances (Gandell et al., 2000).

This study used the definitions and categorization of the three levels of web-ness mentioned above as the yardstick for determining the web-ness of a course on Moodle.

Methodology

The main research question of this study was how many USP courses used Moodle as a web supported, web enhanced or web based classroom. Collection of the initial set of data consisted of retrieving the master list of all the courses that were offered by the University in Semesters 1 and 2 of 2010. This data was obtained from the USP’s Office of Planning and Quality. In addition, the master list of all courses on Moodle for the same time period was obtained from the USP’s Learning Systems Manager together with administrative access to each of these courses. These two lists were then compared and organized by course subject and faculty.

To get the next set and the most important data for this study was to individually examine all the courses on Moodle for Semesters 1 and 2 of 2010 to determine the level of web-ness of each course. Approximately, five weeks were spent doing this, with an average of 20 minutes spent on each course as it was thoroughly examined according to the set criteria (discussed previously in this paper) to determine its level of web-ness. The data collected was analyzed, classified and quantified as the total number of web supported, web enhanced and web based courses on Moodle for Semesters 1 and 2 of 2010. It is important to note that for this study a particular emphasis was given to the use of Moodle tools in a course to deduce its level of web-ness rather than volume of online learning and teaching or the appropriate and/or innovative online pedagogies. Even then, it was sometimes difficult to determine a course’s level of web-ness, particularly for web-enhanced courses because of its four components with each component having its own set of elements. This uncertainty was solved through the application of the previously mentioned cardinal rule: a web enhanced course had to contain at least 60% or more elements of each component.

In this study, only active courses on Moodle for the studied time period were considered. There were some courses which had Moodle course ‘shells’ but the course page or ‘shell’ was blank or empty. Also this study did not include trimester based courses offered by USP.

Results

The University of the South Pacific had offered 491 courses in Semester 1 and 482 courses in Semester 2, 2010. In Semester 1, about 30% or 149 courses of the total of 491 courses offered used Moodle and in Semester 2, about 37% or 179 courses of the total 482 courses offered used Moodle as shown in Table 1. The summary shown in Table 1 is irrespective of different courses’ varying levels of web-ness.

Table 1

Total number of courses offered and total number of courses

using Moodle at USP in Semester 1 and 2 2010.

Semester 1 | Semester 2 | |

Total number of courses offered by USP | 491 | 482 |

Total number of courses utilizing Moodle | 149 | 179 |

% of Moodle usage | 30.35% | 37.14% |

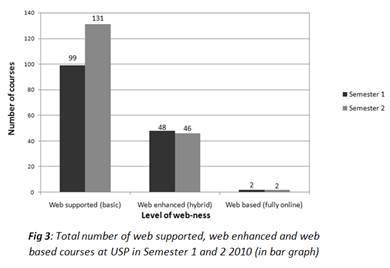

Table 2 and Figure 3 show the summary of the number of courses on Moodle according to the levels of web-ness for Semesters 1 and 2 of 2010.

Table 2

Total number of web supported, web enhanced and web based courses

at USP in Semester 1 and 2 2010

Level of web-ness | Semester 1 | Semester 2 |

Web supported (basic) | 99 | 131 |

Web enhanced (hybrid) | 48 | 46 |

Web based (fully online) | 2 | 2 |

Total | 149 | 179 |

From this study, it was found that in Semester 1, from a total of 149 courses, 99 courses were web supported, 48 courses were web enhanced and just 2 courses were web based. For Semester 2, from a total of 179 courses, 131 courses were web supported, 46 courses were web enhanced and just 2 courses were web based. Similar data is presented on Table 3 but is further elaborated as a percentage of the total courses offered.

Table 3

Total number of web supported, web enhanced and web based courses as a percentage of total number of courses offered at USP in Semester 1 and 2, 2010

Level of web-ness | Sem | % of total course offered in Sem 1 (n=491) | Sem | % of total course offered in Sem 2 (n=482) |

Web supported (basic) | 99 | 20.16 | 131 | 27.18 |

Web enhanced (hybrid) | 48 | 9.78 | 46 | 9.54 |

Web based (fully online) | 2 | 0.41 | 2 | 0.42 |

Total | 149 | 30.35 | 48 | 37.14 |

Discussion

The results of this study provided some interesting insight in the varying levels of web-ness in courses using Moodle at USP. The results indicate a slight increase (6.8%) in the overall use of Moodle, irrespective of the differing levels of web-ness, moving from Semester 1 to 2 despite a slight reduction in the total number of courses being offered by the University. Moodle was used for 37.14% of the courses in Semester 2 compared to 30.35% in Semester 1. As a direct result of this, there was an increase in the web-supported courses from Semester 2 over Semester 1. Moodle was used for 131 (27.18%) of web supported classroom courses in Semester 2, an increase of approximately 7%. Reasons for these two interrelated trends are explained below.

First, the increase can be attributed to increase in awareness and training workshops carried out at regular interval by USP’s Centre for Flexible and Distance Learning (CFDL). CFDL provides series of training workshops on online learning and teaching to lecturers on a regular basis. Ellis & Phelps (2000) suggest that academic staff development that seamlessly incorporates both technical skills and pedagogies ought to serve to model quality teaching practices within any LMS, and, thus, CFDL training workshops integrate pedagogy with technology rather than just providing hands-on practical/technical training. Tremendous work has also been put into raising awareness of Moodle usage at the University since its inception in 2007. Showcases, faculty road-shows and seminars have been organized in the past by CFDL. In July 2010, CFDL hosted a week-long Moodle Forum which enabled lecturers, instructional designers and education technologists to share their experiences. The Forum which was opened by Martin Dougiamas, the founder of Moodle, was well received by the USP community.

An additional reason for increase in the use of Moodle in Semester 2 may be due to the ‘word of mouth’ or ‘catching the bus’ effect which is a direct result of increasing awareness of Moodle use. Morgan (2003) reported similar phenomena at the University of Wisconsin System in USA stating the influence of peers’ recommending an LMS or by setting examples using the technology were some factors that promoted the adoption of LMS among lecturers. It is also important to point out that pressure or persuasion from USP’s Head of Schools and Faculty Deans was another reason for the growth in Moodle usage in Semester 2, 2010. The use of Moodle and online learning and teaching in general also carried ‘more weight’ when lecturers applied for salary increments in staff reviews, which perhaps was also another reason.

Although there was an increase in Moodle usage (due to reasons outlined above), much of the use concentrated on content presentation or as web supported classroom (an increase of approximately 7%). A similar result was also found by Shemla and Nachmias (2007) when they studied the purpose and extent of usage of course websites at Tel-Aviv University in Israel, noting that lecturers conceived course websites to be content providers rather than communication facilitators only realizing, to a limited extent, the pedagogical potential. This is due to the fact the lecturers engaged in design and delivery using LMS face challenges in a variety of areas: technology, logistics, organization and delivery (Dabbagh, 2001) and using Moodle requires technical and pedagogical skills, patience, and dedication. Thus, it is understandable that lecturers new to Moodle will take time to really get in the grips of using LMS as web enhanced or web based classroom, and are “generally much slower to adopt the more complex or interactive parts of the LMS” (Morgan, 2003) thus starting off with the basic use of Moodle in web supported classrooms.

One other trend obvious from the results is that the number of web enhanced courses remained same (48 courses in Semester 1 and 46 courses in Semester 2) and remained very low (Approximately 10% of the total courses offered at USP). This can be attributed to the fact that most lecturers are fairly new to Moodle and to the concept of online learning and teaching. However, their use of Moodle seems to evolve over time, i.e. starting from a basic web supported course, gaining more experience and confidence along the process and, after using Moodle for 2 or 3 semesters, then they start to use more dynamic and interactive Moodle tools in their courses. Morgan (2003) in a study of Faculty’s use of LMS at the University of Wisconsin System in USA noticed a similar situation, reporting that:

Once faculty starts to use a LMS, their use of the technology tends to grow. Nearly, two thirds of the faculty surveyed said that they used a LMS more extensively than they first started using the technology. By far the most important reason given for the growth in their LMS use was that, over time, they began to see the increased uses for it in their teaching. (Morgan, 2003, p. 3)

Finally, the results suggest that despite the increase in courses using Moodle (approximately 7% of courses), the number of web based or fully online courses remained the same and very low (2 courses, approximately 0.4% of the total courses offered at USP). There could be several reasons for this trend; however, the major factor could be that most lecturers at USP are not yet experienced and skilled enough to deliver fully online courses, facilitate online learning and teaching, and to nurture sense of community. And also, perhaps, the web based or fully online model of course delivery may not be preferred by the learners in the region because there are still disparities in terms of internet connectivity, information literacy and access to ICT in the region. On that note, Sikora and Carroll (2002) reported that online higher education students tend to be less satisfied with totally online courses when compared to traditional courses.

Morgan (2003) aptly highlights that one needs to understand how LMS works before one can drive it. There still needs to be lot of work done considering the fact that USP has a very ambitious institutional goal of offering most of its courses fully online. But the slight increase in the overall use of Moodle is a small step towards achieving this feat. The use is anticipated to exponentially grow even more in 2011 after a directive from the University’s Deputy Vice Chancellor (Learning, Teaching and Student Services) instructing all lecturers for a mandatory use of Moodle as part of their course delivery in 2011. With the introduction of new learning technologies in some of the USP courses such as ePortfolios (Prasad, 2010) mobile learning initiatives (Kumar, 2010), open educational resources, game-based learning activities (Totaram, 2010), integrated third party applications (Bhartu, 2010) and podcasting, there are signs that more courses will begin to use Moodle in web enhanced or web based classrooms.

Future Research

This study has several implications for lecturers, instructional designers, education technologists, faculty and university administrators, and researchers particularly for those in the South Pacific region. Similar studies need to be carried out in 2011 and trends should be elicited to see if there are any changes to the level of web-ness in online courses at USP. In addition, this future research should further drill-down faculty-wise, school-wise and programme-wise to identify, classify and quantify level of web-ness in the USP courses and per undergraduate and postgraduate courses. Another area for future study should look at the quality and effectiveness of the web supported, web enhanced and web based courses at USP with strong emphasis given to pedagogical considerations. The levels and volume of learning and teaching occurring online should also be studied. Moreover, future research in this subject should also consider interview data, surveys and questionnaires from lecturers and course designers at USP to understand more about the use of Moodle in courses at USP.

Conclusion

We can conclude that the overall use of Moodle at USP is increasing at a very slow pace. With that, there is an increase in the number of web supported courses but yet the number of web enhanced and web based courses remain very low. There are signs this might slowly change as more lecturers get acquainted with Moodle, build greater understanding of the full pedagogical potential and affordances to use it for a web enhanced or web based classroom. Further exploration, both from the perspective of lecturers and learners, needs to be carried out in this area to fully understand the various levels of use of Moodle at USP.

References

Bento, R. F., & Bento, A., M. (2000). Using the web to extend and support classroom learning. College Student Journal, 34 (4), 603-609.

Bhartu, D. (2010). Innovative online assessment methods: A case study in mathematics, Paper presented at the University of the South Pacific’s Vice-Chancellor’s Forum on Learning & Teaching, The University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji. Retrieved January 16, 2011 from http://www.usp.ac.fj/fileadmin/files/dvc/FlashFiles/Day1/DeepakBhartu/DeepakBhartu.html

Black, G. (2001). A comparison of traditional, online and hybrid methods of course delivery. Paper presented at the Teaching Online in Higher Education Online Conference. Retrieved January 16, 2011 from http://www.ipfw.edu/as/2001tohe/master.htm

Colis, B., & Moonen, J. (2001). Flexible Learning in a Digital World: Experiences and Expectations. London: Kogan-Page.

Dabbagh, N. (2001). The challenges of interfacing between face-to-face and online instruction. TechTrends, 44 (6), 37-42.

Ellis, A. & Phelps, R. (2000). Staff development for online delivery: A collaborative, team based action learning model. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 16 (1) 26-44. Retrieved January 26, 2011 from http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ajet16/ellis.html

Falvo, D. A., & Johnson, B. F. (2007). The use of learning management systems in the United States. TechTrends, 51 (2), 40-45.

Gandell, T., Weston, C., Finkelstein, A., & Winer, L. (2000). Appropriate use of the web in teaching higher education. In B. Mann (Ed.), Perspectives in Web Course Management (pp. 61-68). Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.

Ge, X., Lubin, I., & Zhang, K. (2010). An Investigation of faculty’s perceptions and experiences when transitioning to a new learning management system. Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal, 2 (4), 433-447. Retrieved January 26, 2011 from http://www.kmel-journal.org/ojs/index.php/online-publication/article/viewFile/83/68

Kumar, D. (2010). Introduction of mLearning in the teaching & learning processes at USP, Paper presented at the University of the South Pacific’s Vice-Chancellor’s Forum on Learning & Teaching, The University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji. Retrieved January 16, 2011 from http://www.usp.ac.fj/fileadmin/files/dvc/FlashFiles/Day1/Dinesh/DineshKumar.html

Narwani, A., & Arif, M. (2008). Blackboard adoption and adaption approaches. In M. Iskander (Ed.), Innovative Techniques in Instruction Technology, E-learning, E-assessment and Education (pp. 56-63). Netherlands: Springer.

Mann, B. (2000). Phase theory: A teleological taxonomy of web course management. In B. Mann (Ed.), Perspectives in Web Course Management (pp. 3–25). Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.

Morgan, G. (2003). Key findings - Faculty use of course management systems, EDUCAUSE Centre for Applied Research, Retrieved January 26, 2011 from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/EKF/ekf0302.pdf

Papo, W. (2001). Integration of educational media in higher education large classes. Educational Media International, 38 (2-3), 95-99.

Prasad, D. (2010). The final countdown 3, 2, 1… zero: Launching towards a university wide implementation of an ePortfolio system, Paper presented at the Sixth Pan Commonwealth Forum on Open Learning (PCF6), Kerala, India. Retrieved January 16, 2011 from http://www.pcf6.net/pages/fp/zGB4321.doc

Schmidt, K. (2002). The web-enhanced classroom. Journal of Industrial Technology, 18 (2). Retrieved January 10, 2011 from http://www.nait.org

Sikora, A. C., & Carroll, C. D. (2002). Postsecondary education descriptive analysis reports (NCES 2003-154). US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Saunders, G. & Klemming, F. (2003). Integrating technology into a traditional learning environment: Reasons for and risks of success. Active Learning in Higher Education, 1, 74-86.

Rovai, A., & Jordan, H. (2004). Blended learning and sense of community: A comparative analysis with traditional and fully online graduate courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 5 (2), Retrieved January 10, 2011 from

http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/viewArticle/192/274.%20Accessed%2019th%20March%202006

Shemla, A. & Nachmias, R. (2007). Current state of web supported courses in higher education at Tel-Aviv University. International Journal on E-Learning, 6 (2), 235-246. Retrieved January 26, 2011 from http://www.editlib.org/p/12057

Totaram, R. (2010). Innovative use of Moodle in a undergraduate mathematics for social sciences course at USP, Paper presented at the University of the South Pacific’s Vice-Chancellor’s Forum on Learning & Teaching, The University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji. Retrieved January 16, 2011 from http://www.usp.ac.fj/fileadmin/files/dvc/FlashFiles/Day1/Rajneel/RajneelTotaram.html

Van de Ven, M. (2002). Implementing ICT in education faculty-wide. European Journal of Engineering Education, 27 (1), 63-76.

Woods, R., Baker, J., & Hopper, D. (2004). Hybrid structures: Faculty use and perception of web-based courseware as a supplement to face-to-face instruction. The Internet and Higher Education, 7, 281-297.

Wu, H. (2004). Web based vs. Web supported learning environment – A distinction of course organizing or learning style?. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology Journal, 1, 207-214. Retrieved January 10, 2011 from http://informingscience.org/proceedings/InSITE2004/035wu.pdf

About the Author

Javed Yusuf is an education technologist based at the Centre for Flexible and Distance Learning at the University of South Pacific in Fiji. He is involved in the design and development of courseware for distance, flexible and online delivery. He also plays a leading role in the introduction of new learning technologies and learning design at the University. He has qualifications in computer science, information systems and education technology. His interest lies in educational design for web-delivery, media and digital technologies in education, communications, research, management, evaluation & assessment, and human computer interaction (usability & cognitive processing).

Email: javed.yusuf@usp.ac.fj