| May 2010 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: This paper compare the effectiveness of different kinds of feedback in Computer Assisted Language Learning.

The Effect of Computer-Mediated Corrective Feedback on the Development of Second Language Learners’ Grammar

Parisa Razagifard and Massoud Rahimpour

Abstract

The present study investigated the impact of two types of computer-mediated corrective feedback on the development of learners’ second language (L2) knowledge: (1) implicit feedback in the form of recast, and (2) explicit feedback in the form of meta-linguistic feedback. The participants of this study, 30 beginning level learners of English, were randomly divided into two experimental groups and one control group. The experimental groups completed two computer-mediated focused tasks activities about the target structure in the study. During task-based interaction via text-chat, the learners received focused, corrective feedback when an error was made with the target form. Acquisition was measured by means of the three tests: computerized fill-in-the-blank test, grammatical judgment test, and a meta-linguistic knowledge test. Analysis of the results on the computerized fill-in-the-blank test and the meta-linguistic knowledge test indicated that the experimental groups who received computer-mediated corrective feedback in the form of meta-linguistic feedback and recast differed significantly from the control group. The results obtained from the grammatical judgment test showed some benefits though the values obtained did not reach statistical significance. The findings also indicated computer-mediated corrective feedback in the form of meta-linguistic feedback is more effective than computer-mediated corrective feedback in the form of recast.

Keywords: Corrective Feedback, Recast, Meta-linguistic Feedback, Text-Chat.

Introduction

Computer assisted language learning (CALL) has received a great deal of attention in the field of second language acquisition (SLA) in recent years and every year an increasing number of teachers are using computers in their second language (L2) and foreign language classrooms, (Kawase, 2005). Computers, which entered school life in the late 1950s in developed countries, are still increasing in number day by day throughout the world. Today, they have become more powerful, faster, easier to use, more convenient and cheaper, and they can process and store much more data, as well(Gunduz, 2005).

At the end of the 20th century, the Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) and the Internet have reshaped the use of computers for language learning. Computers are no longer a tool for only information processing and display but also a tool for information processing and communication (Gunduz, 2005). Warschauer (1996a) argues that CMC is probably the single computer application to date with the greatest impact on language teaching. Warschauer (1999) points out that its strength is in the provision of ‘time and place independent’ environment for the interaction of not only one-to-one, one-to-many or many-to-one, but, basically, many-to-many. Nonetheless, as Dhaif (1989) claims computers can never replace the 'live' teacher, especially in language teaching, where the emphasis is on mutual communication between people. It can just play a role in teaching the second or foreign language as an aid to the teacher.

CMC, conventionally, is divided up into two broad categories: (1) asynchronous CMC (ACMC e.g., email and bulletin boards) and (2) synchronous CMC (SCMC e.g., real-time, live discussion via online channels such as chat systems) (Abram, 2003). Synchronous CMC helps learners to expand the exposure to the target language through real-time interaction (Lee, 2008). When learners engage in interaction, they can receive feedback, and have opportunities to produce modified output, all of which facilitate the development of learners’ interlanguage (Long & Robinson, 1998). The absence of nonverbal cues in text chats (e.g., facial expressions) affects the way corrective feedback is generated. The visual salience of written discourse and the self-paced setting in a text-based medium increase learner’ opportunities to take notice of errors and make output modifications including self-repairs (Lee, 2004). To date, the CMC studies, grounded in Long’s Interaction Hypothesis (1996), have focused on how negotiation of meaning elicits corrective feedback using various types of negotiation moves (e.g., clarification requests, recasts) to attain mutual comprehension (Smith, 2003).

Despite the fact that a limited number of studies showed that CMC enhanced the development of grammatical competence through noticing errors in certain syntactical features (e.g., Fiori, 2005; Salaberry, 2000), other reports revealed that lexical errors were the main triggers for negotiation of meaning, whereas syntactical errors were largely ignored (e.g., Sotillo, 2000; Smith, 2003). From a pedagogical point of view, grammatical accuracy and lexical growth should be equally important for the development of L2 language competence. Accordingly, the current study explores learning outcomes following two computer-mediated corrective feedback treatments (recasts and metalinguistic prompts) on development of second language grammar of learners.

Computer Mediated Communication and Interaction

The interactionist perspective on second language acquisition (SLA) argues that conversational interaction in the target language (TL) forms the basis for language development (Smith, 2004). In his most recent version of the Interaction Hypothesis, Long (1996) claims that interactive tasks that promote learners’ negotiation of meaning facilitate the development of a second language. Pica (1994) claims that meaning negotiation, as a particular way of modifying interaction, can accomplish a great deal of SLA by helping learners make input comprehensible and modify their own output and by providing opportunities for them to access L2 form and meaning.

The key interest in CMC, from an interactionist perspective on L2 learning, involves the specific ways in which CMC is relevant to and facilitative of the processes believed to be beneficial to SLA. Among the most important issues is establishing the facility of CMC to supply rich input, promote pushed output, provide plentiful and dynamic feedback, focus learners’ attention on aspects of the TL, and enhance noticing (Smith, 2004). Although the current research in no way suggests that CMC can or should supplant face-to-face communication in the L2 classroom, CMC research has suggested several potential benefits over face-to- face interaction.

These benefits include an increased participation equality among students (e.g., Beauvois, 1992; Sullivan & Pratt, 1996), an increased quantity of learner output (Chun, 1994; Kern, 1995), and an increased quality of learner output (e.g., Chun, 1994; Warschauer, 1996b). There is also evidence that CMC is viewed by students as being less threatening than face-to-face interaction, which often results in an increased willingness to take risks and try out new hypotheses (Warschauer, 1997). Warschauer (1996b), for example, found that students were more inclined to pursue idea-generating discourse and were less inhibited during written production than in oral discussion.

The potential for anonymity may complement this willingness for risk taking as it has been found to create a certain distance between participants that may contribute to an observed atmosphere of critical receptivity (Kern, 1998). Kern, (1995), compared the interaction of French learners in text based online chat with interaction in face-to-face communication, and stated that learners in chat room contexts produced more turns and sentences and used a greater variety of discourse structures. Kern (1995), found that learners using SCMC contributed an average of 2 to 3.5 more turns than those discussing a similar topic in oral interaction.

A heightened quality of learner output was also reported by Kern (1995), who found that students were linguistically more creative and sophisticated during CMC than during traditional whole-class discussions and that 80% of the students reported feeling more confident in writing French during the CMC sessions. Sotillo (2000) compared the discourse functions and syntactic complexity of 25 ESL students’ writing. The results of study indicated that, whereas synchronous discussions elicited conversation that was similar to F2F communication in terms of discourse functions, asynchronous writing promoted more sustained interactions and greater syntactic complexity.

In terms of pushed output, Blake and Zyzik (2003) in a unique study exploring interaction between heritage speakers and learners of Spanish suggested that the demands of electronic chatting seem to force participants to produce the TL. Blake and Zyzik (2003) found that the CMC environment seemed to offer the Spanish heritage speakers a chance to expand their bilingual range, including grammatical , textual, illocutionary, and sociolinguistic competencies. Blake and Zyzik (2003) also suggested that the output elicited by the CMC environment can serve to remedy the incessant problem of disfluency among Spanish heritage speakers by serving to facilitate automatization of language processing.

There is some indication that the text-based CMC medium can amplify students’ attention to linguistic form (e.g., Kern & Warschauer, 2000; Shekari & Tahririan, 2006) by offering learners ample opportunity to notice lexical and grammatical features in the input. As Chapelle (2001) noted, written communication likely affords more opportunity for attention to form than spoken language. The visual saliency of incoming and outgoing messages as well as the ability to reread previous messages may allow students to better attend to such formal aspects without substantially hindering the flow of communication. CMC may also afford learners more processing time, the importance of which has been addressed by Dörnyei and Kormos (1998). This extra time may lead to better comprehension and more accurate production and may also help facilitate a higher quality inter-language than would occur in a non-electronic environment (Smith, 2004).

The modest-yet-growing body of CMC research grounded in an interactionist theoretical framework suggests that learners can and do negotiate for meaning during CMC and that computer-mediated negotiated interaction is quite similar in many ways to that observed in the face-to-face literature. For example, as with face-to-face interaction, lexical items have been found to trigger the vast majority of computer-mediated negotiation, with morphosyntax triggering very little negotiation (e.g., Blake, 2000; Blake & Zyzik, 2003; Toyoda & Harrison, 2002).

CMC has also been found to be a good venue for providing learners opportunities to attend to and engage in pushed output. Finally, task types typically used during face-to-face instruction have proven successful in eliciting high amounts of learner interaction and negotiation in a CMC environment as well (Blake, 2000).

However, today most of the researchers have pointed out that communicative activities which focus solely on meaning processing are not adequate for learning a second language and a certain amount of focus on form is needed (e.g., Ellis 2001; Long , 1996). A focus on form during interaction causes learners to notice certain input features, and compare them with their own output. Therefore, teachers and material designers should consider tasks that result in attention to form while maintaining meaningful communication. The tasks that involve negotiation of meaning and focus on form (also called focused tasks) may encourage noticing of forms and implicit learning (Ellis, 2003). The focused tasks provide a forum for students’ mistakes to appear and therefore, there exists a need for corrective feedback on those mistakes.

Corrective Feedback and Second Language Acquisition

The role of corrective feedback in second language acquisition (SLA) has received much attention in the literature and it is still a topical issue (e.g., Ammar & Spada, 2006; Ellis et al., 2006). Advocates of the nativist theory claim that SLA is driven by exposure to positive evidence and comprehensible input without any need for corrective feedback (Krashen, 1985). However, there are indications that exposure and input alone might not be sufficient for high-quality L2 learning and corrective feedback plays a beneficial role in facilitating the acquisition of certain L2 forms which may be difficult to learn through input alone (Ammar & Spada, 2006).

Implicit and Explicit Corrective Feedback

All corrective feedback is classified either as explicit or implicit in form. In the case of implicit feedback, there is no overt indicator that an error has been committed, whereas in explicit feedback types, there is. Implicit feedback often takes the form of recasts, defined as corrective feedback technique that reformulates the learner’s immediately preceding erroneous utterance while maintaining his or her intended meaning (e.g., in response to “The boy has three toy,” a teacher might respond “The boy has three toys”( (Ellis et al., 2006).

Recasts are TL reformulations by the interlocutor of a learner’s nontarget-like utterances that retain the central meaning while changing the form of the utterance (Long, 1996).The recast functions both to confirm the meaning of the student’s utterance and to correct the form. Recasts may draw learners’ attention to the inconsistency between their utterances and the TL forms (Long & Robinson, 1998).

Schmidt (2001) described ‘noticing’ as a “first step in language building” that is, in integrating new language within the interlanguage system. He claimed that it is only what the learner notices about the input that holds potential for learning. In particular, learners need to notice the gap between their interlanguage forms and the TL form (Doughty, 2001). Thus, in exploring the benefits of recasts, it is important to consider what aspects of recasts highlight the changes made to nontarget-like production. Certain elements may increase the salience of the recast, that is, help to draw the learner’s attention to the recast form. Although according to some researchers, recasts facilitate noticing linguistic items in productive ways, other researchers take a more pessimistic view of their effectiveness (e.g., Lyster, 1998; Panova & Lyster, 2002).

Knowledge about the effectiveness of recasts continues to expand, and it is now widely accepted that their effectiveness can be affected by some factors. Recasts raise the learner’s consciousness of L2 forms in input to restructure their inter-language and finally leads to pick up of target forms. Teachers’ intentions and learners’ perception affect recast effectiveness (Mackey et al., 2007).

Lyster (1998) suggested that feedback options more explicit than recasts are preferable. He discovered that teachers left many errors uncorrected and also repeated correct utterances as often as they recast incorrect utterances. Given these similar response patterns for both correct and incorrect utterances, Lyster and Ranta (1997) concluded that recasts, because they are implicit, are unlikely to benefit learners, who may experience difficulty in differentiating positive and negative feedback.

Second limitation of recasts, which Lyster and colleagues (Lyster, 1998; Lyster & Ranta, 1997; Panova & Lyster, 2002) pointed out, concerns learner repair. According to these researchers, recasts are less beneficial than elicitation moves because, with recasts, the teacher solves the problem for the learners and the learners are under no compulsion to modify their own utterance or to produce “pushed output” (Swain, 1985). Given Swain’s (1985) output hypothesis, opportunity for self-repair is an important consideration. However, although elicitation provides greater opportunity for either self-repair or other-repair, this opportunity is not always realized because self-repair requires at least latent knowledge of the targeted linguistic form. In such cases, recasts may follow unsuccessful self-repair, and the teacher’s recast resolves the knowledge gap (Loewen & Philp, 2006).

Explicit feedback can take two forms: (a) explicit correction, in which the response clearly indicates that what the learner said was incorrect (e.g., “No, not goed—went”) and thus affords both positive and negative evidence or (b) metalinguistic feedback, defined by Lyster and Ranta (1997) as “comments, information, or questions related to the well-formedness of the learner’s utterance” - for example, “You need past tense,” which affords only negative evidence.

According to Lyster (2007), metalinguistic feedback can lead learners to self-repair, whereas recasts can lead only to repetition of correct forms by students. Lyster (2007) argued that self-repair following a metalinguistic feedback requires a deeper level of processing than repetition of a teacher’s recast. Self- repair is thus more likely to destabilize interlanguage forms as learners are pushed to reanalyze interlanguage representations and to attend to the retrieval of alternative forms. In contrast to self-repair following a metalinguistic feedback, repetition of recast does not engage learners in a similarly deep level of processing nor necessitate any reanalysis.

Previous Studies on Corrective Feedback

There are a number of studies that investigated separately whether either implicit or explicit corrective feedback facilitates acquisition. Nicholas et al. (2001) and Ellis and Sheen (2006) provided reviews of the research on recasts. In general, the recast studies demonstrated that implicit feedback of this kind can have a beneficial effect on acquisition, especially when the recasts are more explicit in nature (Ellis et al., 2006). Other studies demonstrated that explicit feedback is of value. Carroll, Roberge, and Swain (1992), for example, found that a group that received explicit corrective feedback directed at two complex French noun suffixes (–age and –ment) outperformed a group that received no feedback, although no generalization of learning to nouns not presented during the treatment occurred.

Results from a number of comparison studies have found advantages for certain types of corrective feedback. Using quasi-experimental research designs with pre-test-treatment, immediate and delayed post-test structures, Ammar and Spada (2006) and Lyster (2004) investigated the effects of recasts and prompts – defined as corrective feedback techniques that push the learners to self-correct – on the acquisition of English possessive determiners and French grammatical gender respectively. Written and oral measures were used as dependent variables in the three testing sessions to measure the effects of the treatments. Ammar and Spada (2006) reported that the prompt group significantly outperformed the recast group on the immediate and delayed written post-tests. Results from the oral test indicated that the prompt group benefited more than the recast group. However, the difference between the two groups was found to be statistically significant only at the time of the delayed post-test.

A similar pattern of results emerged from the study of Lyster (2004) insofar as the prompts group outscored the recast group in both written post-tests. No differences were found between the two groups in the oral tests. Ellis et al. (2006) investigated the effects of recasts in comparison to metalinguistic feedback. An oral-elicited imitation task and a grammaticality judgement task were employed to measure the effects of the corrective feedback techniques on the acquisition of the past tense –ed prior to the treatment (pre-test) immediately after it ended (post-test) and 12 days later (delayed post-test). Results indicated that the metalinguistic group did better than the recast group on both measures at the delayed post-test. When compared with the control group, results showed that the recast group did not perform significantly better than the control group.

While face-to-face comparison studies have found advantages for certain types of corrective feedback over others, the limited number of outcomes-based studies on corrective feedback in CMC has found no such advantage. Loewen and Erlam’s (2006) study, which investigated the relative effectiveness of recasts and metalinguistic prompts administered during small group text-chat interaction, found no significant advantage for either feedback type over the control condition and no significant advantage for one corrective feedback type over the other. Analysis of their participants’ pre-tests suggested that these findings may have been influenced by the learners’ low proficiency with the target form (English past tense -ed), an indicator that they may not have been at a high enough level to internalize and demonstrate gains resulting from the feedback during the short duration of the study.

Similarly, a second CMC comparison study of corrective feedback found no significant difference in gains following two different types of corrective feedback: enhanced and non-enhanced recasts (Sachs & Suh, 2007, cited in Sauro, 2009). Sachs and Suh (2007) incorporated underlining and bolding of key elements of the recast that were related to the targeted form (backshifting of verbs from simple past to present perfect in reported speech). Despite a higher level of form awareness reported by participants in the enhanced condition, no significant difference in target form accuracy was found between the groups.

In other study, Sauro (2009) investigated the effects of two different types of corrective feedback (metalinguistic feedback and recasts) delivered via written SCMC on the development of L2 grammar among intermediate and advanced learners of English. Results showed no significant advantage for either feedback type on immediate or sustained gains in target form knowledge, although the metalinguistic group showed significant immediate gains relative to the control condition.

SCMC as a Context for Research on Corrective Feedback

The features of text-chat that may make synchronous computer mediated communication (text-chat) an ideal context for investigating second language acquisition processes (i.e., noticing, noticing the gap, pushed output) and outcomes from corrective feedback include the visual saliency of forms, the greater processing and planning time, and the enduring as opposed to ephemeral nature of written turns that are recorded on the computer screen (Sauro, 2009).

Written interaction, such as that afforded by text-chat, may help to increase the visual saliency of linguistic forms (Chapelle, 2001), including, for instance, English articles, third person singular –s, and the past tense-ed morpheme. According to Gass (1997), salience can be said to help ensure that particular forms are noticed by the learner and hence lead to rule strengthening. Thus, the visual saliency of linguistic forms during text-chat may help learners to either confirm or disconfirm currently held hypotheses about the target language (TL).

In addition, the slower turn taking in a written conversation, allows interlocutors both to increase the processing time and increase online planning time. The pace of a text-chat conversation is slower than that of a spoken conversation because humans cannot type as quickly as they can speak even in their L1. The increased time of text-chat may also be particularly beneficial for promoting noticing and production of TL forms that typically require greater control (Payne & Whitney, 2002). Williams (2005) points out that one factor affecting what elements of input learners notice is time pressure. Thus the reduced time pressure during text-chat may allow learners the opportunity to notice the linguistic forms in the input than they might notice in real-time spoken input. Furthermore, the reduced speed of text-chat (compared to face-to-face oral conversation) also affords language learners increased planning time to compose their own messages. Thus, the increased online planning time afforded by text-chat may promote not only attention to target language forms in the input but also closer attention to and monitoring of target language output (Sauro, 2009).

The third feature of text-chat that may be beneficial for learners is the enduring as opposed to ephemeral record of the interaction. In contrast to the highly ephemeral nature of most face-to-face oral interaction, one of the key features of interaction via text-chat is an enduring visual record of the exchange in the chat window. The enduring nature of text-chat allows the learners to review and reuse TL forms available in the input. Accordingly, the enduring nature of text-chat permits quick hypothesis confirmation and may promote the reuse of TL forms (Sauro, 2009).

The present study

Synchronous CMC provides an ideal context for investigating second language acquisition processes (i.e., noticing, noticing the gap, pushed output) and outcomes from corrective feedback. It helps students to learn the complex or low salient forms due to the visual saliency of certain forms during written interaction, the amount of processing and planning time afforded by synchronous chat, and the enduring as opposed to ephemeral nature of the turns (Sauro, 2009). Despite the potential advantages of synchronous CMC for facilitating the noticing and learning of these low salient and difficult forms, research on learning outcomes following computer-mediated corrective feedback is still limited (e.g., Loewen & Erlam, 2006; Sauro, 2009). Accordingly, the present study investigates the impact of two types of computer-mediated corrective feedback (metalinguistic and recast feedback) delivered via written SCMC on the development of L2 grammar among beginning learners of English who possess prior knowledge of the target form.

The research was designed to answer the following question:

RQ: What is the effect of computer-mediated corrective feedback on the development of L2 learners’ grammar?

Participants

The study was conducted in Kosar Private School in Meshkinshahr. The participants of the study were 30 beginning level learners of English. They volunteered to participate in this study. The participants were classified as beginning level of learners according to scores on an Oxford Placement Test. After elimination, due to their scores, the final subject pool consisted of 30 participants. The participants ranged in age from 15 to 17. The students were classified into three groups. These three groups were randomlydivided into two experimental groups (experimental group 1 =10 students, experimental group 2 =10 students) and one control group (group 3 =10 student).

Based on a pre-treatment background questionnaire, learners were determined to have similar previous experience working with computers and reported using computers regularly for purposes including e-mail, word processing, Web surfing, and chatting . Two teachers were asked to be the researcher’s assistants. The participating teachers were two female English language teachers (ages: 27 and 33 years). They both held TEFL certificates and had taught adult EFL learners at both beginner and intermediate levels. They were briefed about using chat programs and were interested in the role of computer-mediated corrective feedback in language learning.

Target Structure

Past tense form was chosen as the target structure for two reasons. First, learners at the beginning level were likely to already be familiar with and have explicit knowledge of this structure. Our purpose was not to examine whether corrective feedback assists the learning of a completely new structure, but whether it enables learners to gain greater control over a structure they have already partially mastered. The second reason was that the past tense form is known to be problematic for learners and to cause errors; thus, it was hypothesized that although learners at this level would have explicit knowledge of this structure, they would make errors in its use, especially in a communicative context.

Materials

Instructional Materials

The materials used in this study included two computer-mediated focused tasks activities completed by participants. The selection of tasks was motivated by previous studies (e.g., Ellis et al., 2006; Loewen & Erlam, 2006). These tasks have been tested and used in a number of prior studies (e.g., Ellis et al., 2006; Loewen & Erlam, 2006). The tasks constituted what Ellis (2003) called focused tasks; in other words, they were designed to encourage the use of particular linguistic forms and, to this end, learners were provided with certain linguistic prompts.

Task 1

Learners were given the sequence of pictures, which narrated a short story. They were also given written account of the same story. Learners were told that they would have only a couple of minutes to read the written account of the story and that they needed to read it carefully because they would be asked to rewrite it in as much detail as possible. The story was removed and a set of verbs was given to them to help them rewrite the story and then discuss it. They were told that they would not be able to use any prompts other than the picture sequence and verb list. The opening words of the story were written to clearly establish a context for past tense: “Yesterday, Jack and Alex.....”. (See Appendix A).

Task 2

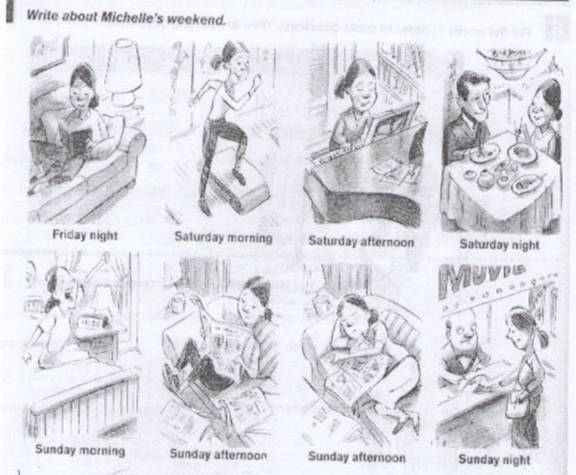

Each student was given the sequence of pictures. The students were asked to write about the pictures. Pictures were chosen to depict actions that would require the use of verbs with past tense forms (Loewen Erlam, 2006). Learners were given two minutes to prepare for writing about Michelle’s weekend (see Appendix B).

Testing materials

Metalinguistic Knowledge Test

Learners were presented with five sentences and were told that the sentences were ungrammatical. The parts of the sentences containing the error were underlined. Learners were asked (a) to correct the error and (b) explain what was wrong with the sentence (in English, using their own words). They were shown one practical example. Each item was presented on a new page and test-takers were told that they were not allowed to turn back (Ellis et al., 2006). Learners scored one point for correcting the error and one point for a correct explanation of the error.

Grammaticality Judgment Test This was a pen-and-paper test consisting of 15 sentences. Of the 15 sentences, 7 were grammatically correct and 8 were grammatically incorrect. The participants were required to (a) indicate whether each sentence was grammatically correct or incorrect, and (b) self-report whether they used a rule or intuition/feeling to judge the sentence (Ellis et al., 2006).

Learners were given two sentences to practice on before beginning the test. For past tense, 7 of the 15 statements presented the target structure in the context of new vocabulary and 8 presented the target structure in the context of vocabulary included in the instruction. Learners’ responses were scored as either correct (1 point) or incorrect (0 points).

Computerized Fill-in-the-blank Test

This was a computer-based test. Learners were presented with 20 items. The participants were required to read the sentences and fill the gaps with the correct forms of given verbs. Learner’s responses were scored as either correct or incorrect. Each correct answer received one point and each incorrect answer received a zero

Procedure

During the preparation period, Yahoo! Instant Messenger (YIM) chat program was downloaded and set up in each computer. During the first meeting, the students participated in a training session where they received an introduction to the YIM chat program, which was to be used in the study. The YIM chat program was chosen as the interface because it resembles various free chat software and Web-based programs available today. During this session, participants were given two practice tasks to complete. These tasks were shortened versions of similar tasks used in the treatment. The tasks were implemented according to Ellis’ (2003) definition of tasks; that is, they included a gap, they required learners to focus primarily on meaning and to make use of their own linguistic resources, and they had a clearly defined outcome.

The interaction took place outside the classroom and outside of class time, in a small room equipped with computers. The experimental groups completed two focused tasks during the treatment sessions. Each learner was paired up randomly with one of the teachers or researcher for each activity; partners had 20 minutes to work together to complete the tasks.

During this collaborative period, English-teacher partners supplied corrective feedback when an error was made with the target form. Prior to the study, the teachers were briefly familiarized with the general categories of interactional feedback, including recasts and metalinguistic feedback, and they used them whenever they felt it was needed and appropriate. The learners received corrective feedback while performing the tasks. For example, experimental group one received implicit feedback in the form of recasts, as in (1).

(1) Yalda: yesterday, Jack and Alex go to the river for a picnic.

Teacher: went

Yalda: Jack and Alex went to the river for a picnic and...

The learners in experimental group 2 received explicit feedback in the form of metalinguistic information, as in (2).

(2) Nasim : . . . and the cow look at the picnic basket

Teacher: look, you need past tense.

Nasim: the cow looked at the picnic basket and....

This was typical of the corrective feedback episodes in the current study; the instructor first repeated the error and then supplied the meta-linguistic information.

The study took place during three weeks. Students in the experimental groups participated in four sessions that consisted of two computer-mediated focused tasks activities: a story completion task and picture description task. The post-tests were completed after four treatment sessions. During the testing session, three tests were administered in the following order: computerized fill-in-the-blank test, grammaticality judgment test, and metalinguistic knowledge test. The tests were designed to measure the effect of both types of feedback on development of L2 grammar knowledge of the participants.

Post-tests Results

The effect of both types of feedback was assessed through three tests: the meta-linguistic knowledge test, the grammaticality judgment test, and the computerized-fill-in-the-blank test. Three separate means and ANOVAs were calculated for the groups on three tests. Group differences were considered significant when p <.05. The analysis of data is presented below.

Analysis of Results in the Metalinguistic Knowledge Test (MKT)

The descriptive statistics of MKT, including group means and standard deviations, for each group appear in Table 1.

Table 1

Results of Descriptive Statistics for MKT

Mean | Maximum | Std. Deviation | Minimum | |

Experimental Group 1 (recast) | 6.5 | 1.43 | 8 | 3 |

Experimental Group 2 (metalinguistic) | 7.00 | 1.33 | 9 | 5 |

Control group (placebo) | 5.2 | 1.31 | 7 |

As the above table shows, three groups’ performances on MKT are different. The results indicated that the two experimental groups who received computer mediated corrective feedback in the form of metalinguistic feedback and recast feedback (metalinguistic group and recast group) obtained higher mean scores

As the above table shows, three groups’ performances on MKT are different. The results indicated that the two experimental groups who received computer mediated corrective feedback in the form of metalinguistic feedback and recast feedback (metalinguistic group and recast group) obtained higher mean scores (X =7.00 and X =6.50, respectively) in comparison with control group (X =5.2) that did not receive any feedback. Also, the metalinguistic group’s mean (X =7.00) was higher than that of the recast group (X =6.50). Figure 1. displays means for three participating groups on MKT.

Figure 1. displays means for three participating groups on MKT.

One way analysis of variance (one way ANOVA) was employed to find out if the difference between the three groups was significant.

The result of one way ANOVA revealed that the difference between groups was significant in MKT. Technically speaking (F= 4.653, p = .018) proved to be significant at the .05 level in terms of the dependent variable. A post-hoc comparison was run to exactly pin down where the difference lays. The results showed that there was a meaningful difference between the experimental groups who received computer-mediated corrective feedback and the control group who did not receive any feedback. However, the difference between the two experimental groups (the recast group and the metalinguistic group) was not statistically significant.

Analysis of Results in the Grammaticality Judgment Test (GJT)

Group means and standard deviations for the three participating groups on GJT appear in Table 2.

Table 2

Results of Descriptive Statistics for GJT

Mean | Maximum | Std. Deviation | Minimum | |

Experimental Group 1 (recast) | 12.6 | 1.07 | 15 | 11 |

Experimental Group 2 (metalinguistic) | 12.8 | 1.68 | 15 | 10 |

Control group (placebo) | 11.7 | 1.05 | 13 | 10 |

As the above table shows, both metalinguistic and recast groups obtained higher mean scores (XX=12.6 and XX =12.8, respectively) in comparison with the control group (XX=11.7). Also, the metalinguistic group’s mean (XX=12.8) was higher than that of recast group (XX=12.6). Figure 2. displays the means for three participating groups on GJT.

Figure 2. Group means for the CJT

The results of the one way ANOVA revealed that the difference between groups was not statistically significant (F= 2.011, p= .153) at the .05 level in terms of dependent variable. Analysis of Results in the Computerized Fill-in-the-blank Test (CFBT)

Table 3

Results of Descriptive Statistics for CFBT

Mean | Maximum | Std. Deviation | Minimum | |

Experimental Group 1 (recast) | 17.20 | 1.47 | 19 | 14 |

Experimental Group 2 (metalinguistic) | 17.80 | 1.87 | 20 | 13 |

Control group (placebo) | 14.90 | 2.02 | 17 | 10 |

As the above table shows, the two experimental groups (the metalinguistic group and the recast group) obtained higher mean scores (XX =17.80 and XX =17.20, respectively) in comparison with the control group (XX=14.90). Also, the results indicated that the metalinguistic group’s mean (XX= 17.80) was higher than that of the In recast group (XX=17.20). Figure 3 displays the group means graphically.

Figure 3. Group means for the CFBT

In one way ANOVA was administered to find out if the difference between groups was significant. The results of th is one way ANOVA, provided in table 4.7, revealed that the difference between groups was significant. Technically speaking (F= 7.182, p= .003) proved to be significant at the .05 level in terms of the dependent variable.

A post-hoc comparison was run to determine exactly where the difference lies. The Tukey’s post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that the control group has meaningful differences with both the metalinguistic group and the recast group. In other words, both experimental groups (metalinguistic and recast group) significantly outperformed the control group. However, the results did not show such a significant difference between the recast group and metalinguistic group.

Discussion

In summery, the findings of the present study suggest that, at least in a chat environment, recasts and metalinguistic feedback were effective. Learners in the two experimental groups (metalinguistic and recast groups) benefited more than those who were in the control group (i.e., with no corrective feedback). Furthermore, comparisons of the results indicated the experimental group that received computer-mediated corrective feedback in the form of metalinguistic information outperformed the group that received computer-mediated corrective feedback that reformulates the error in the form of recasts.

Students’ inability to benefit from recast feedback to the same extent as metalinguistic feedback may be due to the differential noticeability of both corrective feedback techniques. Although no direct measure of noticing was used in the present study, it may be argued that learners were unable to notice recasts. In other words, learners in the recast group might have been able to detect the reformulations but could not store them in long-term memory for subsequent retrieval and accurate use. Despite the protracted processing time the written synchronous computer-mediated communication environment afforded participants, reformulations that occurred during the interaction may still have been less likely to be noticed. Metalinguistic feedback, on the opposite, by explicitly signalling the presence of an error and pushing the learners to modify their own output, might have been more noticeable and hence more effective.

Concern with correction of mistakes is the second principal factor that might have contributed to the superior results of metalinguistic feedback over recast feedback. Learners in the metalinguistic feedback group were pushed to correct their ungrammatical utterances, which had the potential to take up to 100% of the time. More importantly, all of the repairs were student-generated. However, and as Van den Branden (1997) pointed out, metalinguistic feedback always encourages the learner to take part in the process of repair, which puts him or her in the appropriate framework to at least acknowledge the suggested solution and, therefore, to notice it. So whether the reformulation was provided by the student who initially produced the error or by his or her peers, the learner was always forced to confront his or her errors and to revise the pertinent hypotheses.

In the recast group, however, the teacher was the one who always provided the correct form. Students had neither an obligation nor an opportunity to draw on their own resources in order to try to come up with the correct grammatical form. In other words, the teacher solves the problem for the learners and the learners are under no compulsion to modify their own utterance or to produce “pushed output” (Swain, 1985). Although it is true that the teacher’s reformulations might have led to uptake in the recast group, uptake following recasts is not necessarily evidence of hypothesis re-evaluation, noticing, and L2 learning. As mentioned previously, even though learners’ reactions to teachers’ recasts might be the result of hypothesis testing or evaluation, they might also simply be repetitions that do not involve any analysis. Therefore, it is not only the quantity of uptake opportunities that might have led to the differences between the metalinguistic group and the recast group but also the nature of the uptake opportunities.

In contrast, metalinguistic feedback, in part due to its overtly corrective nature, tended not to go unnoticed by the participants, as the examples in (3) and (4) suggest (see, next page). In both episodes, the teacher’s feedback move overlaps with the learner’s preceding move but, because the metalinguistic feedback is longer, it might have been better attended to and perceived as overtly corrective. In both episodes, however, the learner successfully repairs the error following the feedback move, but, again, there is evidence of greater awareness that repair is needed in the metalinguistic episode. Whereas in (3) the learner simply repeats the reformulated past tense verb, in (4) the learner’s “yes” seems to overtly acknowledge that repair was required. Thus, metalinguistic feedback—in comparison to recasts—seems more likely to lead to greater depth of awareness of the gap between what was said and the target norm, thereby facilitating the acquisition of implicit knowledge. It is also important to recognize that the metalinguistic feedback, as illustrated in (4), does not intrude unduly in the communicative flow of the activity. It constitutes a brief time-out from communicating, which allows the learner to focus explicitly but briefly on form. The effectiveness of the metalinguistic feedback, therefore, might derive in part from the high level of awareness it generates and in part from the fact that it is embedded in a communicative context.

(3) Yalda: yesterday two boys, Jack and Alex go to the river for a picnic (

Oct 10, 2009 9:24:56 AM)

Teacher: went (Oct 10, 2009 9:25:5 AM)

Yalda: went to the river for a picnic (Oct 10, 2009 9:25:56 AM)

(4) Nasim: and the cow look at the picnic basket (Oct 10, 2009 11:10:15 AM)

Teacher: look, you need past tense (Oct 10, 2009 11:10:50 AM)

Nasim: looked -yes (Oct 10, 2009 11:11: 5AM)

Nasim: she looked at the picnic basket and smelled the

cakes and sandwiches (Oct 10, 2009 11:11:50 AM)

What is also revealed in these excerpts is that there is slower turn taking in text-chat. According to Sauro (2009) the increased time that is afforded in text-chat may also be particularly beneficial for promoting noticing and production of TL forms that typically require greater control. Williams (2005) points out that one factor affecting what elements of input learners notice is time pressure. Thus, the reduced time pressure to process incoming messages during text-chat may allow learners the opportunity to notice a broader range of linguistic forms in the input than they might notice in real-time spoken input.

Furthermore, the reduced speed of text-chat (compared to face-to-face oral conversation) also affords language learners increased planning time to compose their own messages. Thus, the increased online planning time afforded by text-chat may be particularly beneficial for promoting not only attention to target language forms in the input but also for promoting closer attention to and monitoring of target language output. Both increased processing time (Payne & Whitney, 2002) and increased online planning time. Thus, these features of the text-chat medium together with higher rates of uptake following metalinguistic feedback in comparison with recast feedback may have given the participants in the metalinguistic group the time and opportunity to notice, analyze and internalize the corrective feedback.

Conclusion and Pedagogical Implications

This study has examined the relative effectiveness of two different types of computer-mediated corrective feedback on the development of L2 target form knowledge. Despite the fairly limited amount of feedback generated, the results demonstrated higher gains in development of grammar knowledge for groups who received computer-mediated corrective feedback in comparison to the control group. The findings showed that computer-mediated communication provided favorable conditions for feedback negotiation and also helped learners to focus on their grammar errors.

This study indicates some support for using text-based CMC to expand learners’ grammatical accuracy. Thus, it would be reasonable to allocate some time to the training of teachers in this regard. The findings of this study may also have implications for the design of learning activities to be completed using instant messaging or SCMC. As L2 learners collaborate in online communicative activities with their partners, focused corrective feedback might eventually lead to successful learner uptake. These constitute supplemental learning activities that can take place outside the traditional classroom environment.

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

This study was narrowed down in terms of its participants, structure in focus, techniques of corrective feedback, etc. It seems necessary to point out some further research needs to be done in this regard. Future research should address the limitations outlined as well as several other areas. For example, the study only considered of two different types of computer-mediated corrective feedback (metalinguistic feedback and recast) and not other types of corrective feedback. It is suggested that similar studies be conducted with other types of computer- mediated feedback whether implicit ones or explicit ones, such as clarification request, elicitation, etc.

Moreover, more comprehensive studies could be done to investigate the effect of more than two techniques at a time on language acquisition. Since the present study focused on only one structure in English, similar studies could examine the accuracy gains in terms of other structures in English or any other languages. Finally, this study could be replicated with learners at higher levels of language proficiency.

References

Ammar, A., & Spada, N. (2006). One size fits all? Recasts, prompts an L2 learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28, 543–574.

Abrams, Z. I. (2003). The effects of synchronous and asynchronous CMC on oral performance in German. The Modern Language Journal, 87(2), 157–167.

Beauvois, M. H. (1992). Computer-assisted classroom discussion in the foreign language classroom: Conversation in slow motion. Foreign Language Annals, 25, 455–464.

Blake, R. (2000). Computer mediated communication: A wind on L Spanish interlanguage. Language Learning & Technology, 4, 120–136.

Blake, R., & Zyzik, E. (2003). Who’s helping whom? Learner/heritage-speakers’ networked discussions in Spanish. Applied Linguistics, 24, 519–544.

Carroll, S., Roberge, Y., & Swain, M. (1992). The role of feedback in adult second language acquisition: Error correction and morphological generalizations. Applied Psycholinguistics, 13, 173–198.

Chapelle, C. (2001). Computer applications in second language acquisition: Foundations for teaching, testing, and research. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Chun, D. M. (1994). Using computer networking to facilitate the acquisition of interactive competence. System, 22, 17–31.

Dhaif, H. A. (1989).Can computers teach languages? English Teaching Forum. 27(3), 17–19.

Dörnyei, Z., & Kormos, J. (1998). Problem-solving mechanisms in L2 communication. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20, 349–385.

Doughty, C. (2001). Cognitive underpinnings of focus on form. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 206–257). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, R. (2001). Introduction: investigating form-focused instruction. Language Learning,

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R., Loewen, S., & Erlam, R. (2006). Implicit and explict corrective feedback and the acquisition of L2 grammar. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(2), 339–368.

Fiori, M. (2005). The development of grammatical competence through synchronous computer-mediated communication. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 567–602.

Gass, S. M. (1997). Input, interaction, and the second language learner. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gunduz, N. (2005). Computer assisted language learning. Retrieved April 25, 2009, from http://jlls.org/Issues/Volume1/No.2/nazligunduz.pdf

Kawase, A. (2005). Second language acquisition and synchronous computer mediated communication. Retrieved April 17, 2009, from http://www.tc.columbia.edu/tesolalwebjournal.

Kern, R. (1995). Restructuring classroom interaction with networked computers: Effects on quantity and characteristics of language production. The Modern Language Journal, 79, 457–476.

Kern, R. (1998). Technology, social interaction, and FL literacy. In J. A. Muyskens (Ed.) New ways of learning and teaching: Focus on technology and foreign language education (pp. 57–92). Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Kern, R., & Warschauer, M. (2000). Theory and practice of network-based language teaching. In M. Warschauer & R. Kern (Eds.), Network-based language teaching: concepts and practice (pp. 1–19). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. London: Longman.

Lee, L. (2004). Learners’ perspectives on networked collaborative interaction with native speakers of Spanish in the U.S. Language Learning & Technology, 8(1), 83–100.

Lee, L. (2008). Focus-on-form through collaborative scaffolding in expert-to-novice online interaction, Language Learning & Technology, 12, 53–72.

Loewen, S., & Erlam, R. (2006). Corrective feedback in the chatroom: An experimental study. Computer Assisted Language Learning 19(1), 1–14. language grammar. Language Learning & Technology, 13, 96–120.

Loewen, S., & Philp, J. (2006). Recasts in the adult L2 classroom: characteristics, explicitness and effectiveness. The Modern Language Journal, 90(4), 536–556.

Long, M. H. (1996). The role of linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. Richie & T. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413–478). San Diego: Academic Press.

Long, M. H., & Robinson, P. (1998). Focus on form: Theory, research and practice. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in second language acquisition (pp. 15-41).

Lyster, R. (1998). Recasts, repetition, and ambiguity in L2 classroom discourse. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20, 51–81.

Lyster, R. (2004). Differential effects of prompts and recasts in form-focused instruction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26, 399–432.

Lyster, R. (2007). Learning and teaching languages through content: A counter-balanced approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lyster, R., & Ranta, L. (1997). Corrective feedback and learner uptake: Negotiation of form in communicative classrooms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, 37–66.

Mackey, A., Al-Khalil, M., Atanassova, G., Han, M., Logan-Terry, A., & Nakatsukasa, K. (2007). Teachers’ intentions and learners’ perceptions about corrective feedback in L2 classrooms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition , 1,129–152.

Nicholas, H., Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. (2001). Recasts as feedback to language learners. Language Learning , 51, 719–758.

Payne, J.S., & Whitney, P.J. (2002). Developing L2 oral proficiency through synchronous CMC: Output, working memory, and interlanguage development. CALICO Journal, 20(1), 7–32.

Pica, T. (1994). Research on negotiation: What does it reveal about second-language learning conditions, processes, and outcomes? Language Learning, 44, 493–527.

Salaberry, M. R. (2000). L2 morphosyntactic development in text based computer mediated communication. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 13(1), 5–27.

Swain, M. K. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. M. Gass & C. G. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition (pp. 235–253). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Panova, I., & Lyster, R. (2002). Patterns of corrective feedback and uptake in an adult ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 36(4), 573–595.

Sauro, S. (2009). Computer-mediated corrective feedback and the development of second language grammar. Language Learning & Technology, 13, 96–120.

Schmidt, R. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 3–32). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shekary, M., & Tahririan, M. H. (2006). Negotiation of meaning and noticing in text-based online chat. The Modern Language Journal, 90(4), 557–573.

Smith, B. (2003). Computer-mediated negotiated interaction: An expanded model. The Modern Language Journal, 87(1), 38–57.

Smith, B. (2004). Computer-mediated negotiated interaction and lexical acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26(3), 365–398.

Sotillo, M. S. (2000). Discourse functions and syntactic complexity in synchronous and asynchronous communication. Language Learning & Technology, 4(1), 82–119.

Sullivan, N., & Pratt, E. (1996). A comparative study of two ESL writing environments: A computer assisted classroom and a traditional oral classroom. System, 29, 491–501.

Toyoda, E., & Harrison, R. (2002). Categorization of text chat communication between learners and native speakers of Japanese. Language Learning & Technology, 6, 82–99.

Van den Branden, K. (1997). Effects of negotiation on language learners’ output. Language Learning, 47, 589–636.

Warschauer, M. (1996a). Computer-assisted language learning: An introduction. Retrieve April 18, 2009, from http://www.gse.uci.edu/faculty/markw/call.html

Warschauer, M. (1996b). Comparing face-to-face and electronic communication in the second language classroom. CALICO Journal, 13, 7–25.

Warschauer, M. (1997). Computer-mediated collaborative learning: Theory and practice. The Modern Language Journal, 81(4), 470–481.

Warschauer, M. (1999). Electronic Literacies: Language, Culture, and Power in Online Education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Williams, J. (2005). Form-focused instruction. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 671–691). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

About the Authors

Parisa Razagifard graduated from Islamic Azad University of Ardabil with an M.A. degree in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL). She is interested in CALL and online learning.

prazagifard@yahoo.com

Massoud Rahimpour is a Professor holding an M.A in teaching English from the University of Oklahoma City in USA and Ph. D in applied linguistics from The University of Queensland in Australia. He lectures in the areas of SLA, syllabus design and TESOL methodology at the University of Tabriz. Prof. Rahimpour has presented and published papers in international conferences and journals. He has also supervised many M.A and Ph. D theses.

Appendix A

Story Completion Task

Story Completion Task

Appendix B

Picture Description Task

Michelle did different activities last weekend. Write sentences about her weekend.